Michael Taft: Strange how some things don’t get into the debate. For instance, the ESRI’s recent Recovery Scenarios judged the Government’s fiscal strategy a failure. It estimated that not only will the Government fail to bring public finances under control by 2014 (if we take the Maastricht guideline as the ‘control’ threshold), it will not be able to do so by 2020. Did any of this get into the debate? Were there discussions on the failure of spending cuts? No. The debate is impervious to such awkward interventions. Spending cuts are good. No amount of reality will be allowed to perturb the consensus.

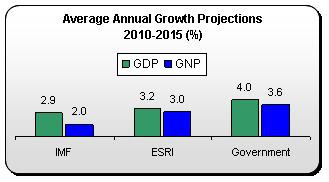

The ESRI presented two growth scenarios for the Irish economy – high-growth and low-growth. In reality, the low-growth scenario is more likely for the simple reason that it is not really ‘low’. It’s lower than the Government’s projections (which have been labelled ‘optimistic’ by the IMF and the OECD) but higher than the IMF estimates. So it’s pretty much in the mid-range.

On the basis of this low-growth scenario, the ESRI says the Government cannot reach the Maastricht threshold – not by 2014, not by 2015 not even by 2020.

• By 2015 the deficit is estimated to be 4.1 percent (not counting any banking subsidies)

• By 2020 the deficit is estimated to be 4.5 percent

In addition, they estimate our overall debt levels will be 102 percent of GDP in 2015, rising to 106 percent five years later.

The reason the deficit and debt start rising after 2015 is because the ESRI estimates that real growth will start to ease off, falling from an average 3.2 percent over the next five years, to 2.1 percent afterwards. On this basis, we would have to cut the deficit to well below -3 percent by 2015, just to ensure we don’t rise above it again in a few years. They summarise the problem:

‘The lower level of economic activity would reduce government revenue from taxation while the higher unemployment rate and borrowing would increase government expenditure on welfare payments and interest payments. This would result in a significant deterioration in the general government balance . . ‘

So why, according to the ESRI, would this state of affairs come about? They first assume the economy won’t respond to increased world growth as robustly as in the past. But they also point out that a poorly functioning banking system, higher cost of capital and structural unemployment could also contribute to a low-growth scenario.

What they don’t mention is the impact of the Government’s deflationary cuts - which is strange since they point out that the Government’s €3 billion fiscal contraction in the 2011 budget will cut economic growth (by approximately 1 percent – though this was before the Government’s announcement that spending cuts, which are more deflationary, will play a more prominent role in the composition of the contraction).

It is even stranger since they have just released a revised set of fiscal multipliers, updating their paper from last year. These updated multipliers show that they previously under-estimated the impact of spending cuts on economic growth:

• A €1 billion cut in public sector wages will reduce GNP by 0.4 percent (previously it was 0.3 percent)

• A €1 billion cut in public sector employment (about 17,000 jobs) will reduce GNP growth by 1.0 percent (previously t was 0.9 percent)

These might seem marginal but given the scale of cutbacks the Government (€2.4 billion in pay cuts, €3.6 billion in non-wage consumption, €2.6 billion in investment cuts), it all adds up.

The key metric is employment and this, more than anything else, helps explain the low levels of growth and, so, the failure of the Government’s fiscal policy. The ESRI estimates that employment will grow by an average 1.3 percent between 2010 and 2015. This compares to the Government’s estimate of 2.0 percent average.

Again, this might not seem much but add it up. But by 2015, the ESRI is estimating we will have approximately 70,000 fewer jobs than the Government’s projections. When you factor in the impact on tax revenue, unemployment costs and the significant social costs of long-term and structural unemployment – you start to see why the Government’s fiscal strategy will fail.

None of this should come as any news – if we were fortunate to get the news: the IMF similarly projected the Government’s fiscal strategy will fail. So, too, did the Ernst & Young / Oxford Economics report (though they held out hope that the deficit might come under control by 2018/2019 – but only at growth rates that exceed the ESRI’s estimates).

Of course, some might be tempted to say, that after nearly €9 billion of spending cuts with the prospect of billions more planned, all we need to do is cut just that little bit more. Just dig a little deeper and we’ll get out of the hole. But that’s the problem – every new estimate, every new projection tells us that fiscal consolidation is getting further and further away the more we cut. How much longer do we go along with this ‘Boxer mentality’ in the face of an emerging consensus that the Government’s strategy is flawed at its core; that no amount of tweaking will rescue it. Indeed, further cuts, in addition to what the Government is planning, will only undermine economic and employment growth even more. What will we do then? Call for even more cuts? How deep does the hole have to get before we stop digging?

So what have got? Low growth, escalating debt, high unemployment and emigration, sluggish economy – and the failure to repair public finances; if the ESRI buried the Government’s fiscal consolidation strategy, it also buried the McCarthy report. You probably didn’t hear about that either.

That’s why my next post will deal with that.

7 comments:

As I see it the various analyses and projections emerging as the months go by are only beginning to get closer to plumbing the depths of the hole into which the policies (and non-policies) of successive governments have tipped the economy - and are merely extending the time needed for it to get out.

And as to the international bond market (frequently berated on this board) we are up to our neck in hock to it. This didn't have to be the case; with appropriate fiscal policies the national debt could have been paid down, the tax system would be more equitable and sustainably based and the wild excess of the property bubble avoided. But they weren't and we are where we are.

With the debt/GNP ratio (a more accurate measure of the ability to service debt) approaching 100% the bond market is getting reluctant to advance more credit, unless it sees evidence of action to curtail the appetite. (The ability of the NAMA merry-go-round to allow the banks to buy government bonds is shiedling the government from fully testing the strength of this reluctance, but it's something that it would be unwise to test to destruction.)

And it may not be a reluctance to advance additional credit at a high coupon (even though some buyers might reckon they are overweight with Irish sovs.); it could simply be well-justified concerns about the flakiness of the Euro Stabilisation Fund. If things were to go pear-shaped, the full recovery of existing low-coupon bonds could be threatened. The German government wants to preserve the EZ as a political project, but it is fighting a very strong popular mood to let the PIGS go hang. (And again, it wouldn't be wise to create the circumstances which would test the resolve of a surprisingly weak German government.)

Finally, the desire of the market to advance more credit may be being dulled by a government sitting on billions of Euros of state assets generating a return much less than the government's cost of funds.

I suspect the appointment of the Asset Review Group may be a purely politcial exercise without any serious intent, but it does send a signal to the market that might buy some time.

For anyone still unaware of the reality this is a timely post.

Ireland is heading for a lost decade. The only item not mentioned here is the impact of the Labour/Fine Gael government economic policies 2012-2017.

These are likely to introduce progressive taxation on pensions, property and other middle class subsidies. Their effect on growth will however be minimal.

Increasing immigration, crime and social unrest are some of the news items likely to dominate the media in the next few years.

You get what you deserve.

@Other anonymous

"These are likely to introduce progressive taxation on pensions, property and other middle class subsidies."

I always smile when such subsidies are mentioned in disapproving tones, as if the middle class are somehow pilfering from the state coffers. The fact that those coffers are largely filled by the very same middle class seems to be lost on the class warriors denouncing tax relief on pensions and mortgage interest.

Its got to the point where supposed middle class parents like teachers, nurses and engineers crucified with tax, mortgage and childcare costs are now less well off in net terms than welfare recipients on the One-Parent Family Payment plus Half-Rate Jobseekers Allowance plus Medical Card plus Back to School Allowance plus Rent Allowance or subsidized social housing.

So if it will be actual ability to take a further hit, as opposed to class labels, that determines who pays under Labour ... then maybe the beleaguered middle class should get a break for once.

Michael what is your recommendation for recovery?

I would propose a Land Valuation Tax as proposed by Constantin Gurgiev to help stimulate the economy by also reducing income and vat rates, simplying tax code and introducing basic income to replace social welfare.

Brendan - I'm aware of the Site Value Tax and the debate surrounding its efficiency. Clearly, such a tax can have a role to play in a comprehensive property tax (one that includes all forms of property, including financial property). One thing I would be concerned about - and you might have some data on this or know where to get it - is the income distirbution impact. The ESRI, for instance, shows that a residential property tax would be only mildly progressive. How would a site value tax impact? It is doubtful in the medium term that it could work to reduce current rates of income tax or VAT - as we will require a substantial increase in the level of tax revenue to both resource a European level of public services and infrastructure, along with achieving fiscal consolidation. But to the extent that it broadens the tax base, it certainly should be discussed in detail.

Again, the principles informing Basic Income could assist in integrating the tax and social welfare systems and, so, remove step effects and income/unemployment traps. This would primarily benefit those on low-incomes. Social Justice's proposals re: refundable tax credits would be a welcome step.

As to recovery - as I've written in several posts here and on Notes on the Front, the overriding priority is to boost investment and employment. That is the only way to sustainable growth.

Thanks Michael, new to site, haven't seen your other posts. Income distribution models requires research I agree. This is Constantin's research paper http://www.commissionontaxation.ie/submissions/Other//J07%20-%20supplementary.doc

I presume you mean mostly private investment rather than government lead borrowed investment money.

Bendan - thanks for the link. Where should investment come from? Private sector investment has been hammered of late (we are now back to pre-2000 levels of investment). That's not going to change until we restore growth in the domestic economy. So we have a chicken-and-egg situation: we can't get growth until we get investment; and we can't get investment until we get growth.

And even if there is growth, there's another problem highlighted by the Davy Stockbroker report (http://www.davy.ie/content/pubarticles/economy20100219.pdf)is that we shouldn't rely on private investment necessarily being productive.

This leads us to the public sector driving investment for the medium-term: Exchequer, public enterprise, Pension Fund. To the extent that private investment can be leveraged in, great. But the driver will not, in the first instance, come from the private sector.

As to paying for it - obviously public non-exchequer sources such as public enterprise and the Pension Fund wouldn't impact on the general government balance. And even where the Excehquer does spend the money - it need not come from borrowed money. One small example can be found in my latest post.

Post a Comment