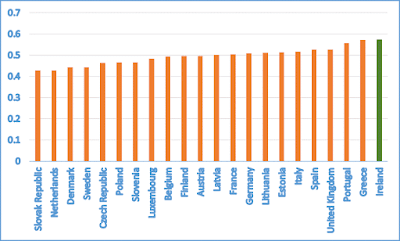

Both charts show the Gini coefficient of income distribution: the lower the Gini coefficient the more equal the society. The first (Figure 1a) shows Ireland as the most unequal society within the EU: the Gini is higher than for any other member state.

|

| Figure 1a Gini, market incomes 2013 |

By contrast, in the second (Figure 1b) shows Ireland to be boringly normal: Ireland's Gini is in the middle of the range.

|

| Figure 1b Gini, disposable incomes 2013 |

If you want to portray Ireland as some sort of unequal disaster zone, you take Figure 1a. Yet what matters to most people is how much income they have after deduction of direct taxes, and conversely also after receipt of state benefits and pensions. Figure 1b thus is closer to the everyday experience of inequality.

Comparing the two charts in Figure 1 shows the impact of the taxation system (or at least of direct taxation) and of the benefit system on income. In other words, the comparison begins to show the impact of the state on inequality. Nearly everywhere the welfare state reduces inequality, but usually to the same extent. Thus most countries are in more or less the same position in both the two charts, but Ireland is one of the few exceptions. In Ireland the welfare state and the system of direct taxation reduce income inequality to a much greater extent than in most other countries.

Of course there are lots of qualifications to this argument. As TASC’s recent inequality report stressed, simply comparing disposable income ignores the extent to which people may have to pay for services in one country where they are cheaper or even free in other countries. For example, Ireland has long been notorious for the high cost of and limited provision of childcare (though after the new budget this may change); Ireland now has very limited provision of social housing. Furthermore, changes in prices may differentially affect different income groups. For example, recent rises in housing costs (mortgage interest payments and rent) have affected all income groups, but the poorest have been especially hard hit (Savage et al 2015). However, there is no reason why this should always be the case – falls in the price of basic goods such as food will usually disproportionately benefit the poorest groups! Finally it is important to be remember that measurements of inequality are by themselves simply measures of relative difference: they say nothing about actual deprivation and actual living standards. Indeed for all the real recovery of the last few years, TASC’s Inequality Report rightly stresses that the level of material deprivation in Ireland is still rising (Hearne and McMahon 2016: 43).

The hard work of the Irish state was

especially clear in the first years of the crisis (Wickham 2015). As Figure 2 shows, between 2007 and 2010 the rise

in the Gini for market incomes in Ireland was the largest in the OECD, but the

increase of disposable income was much lower. This was especially the result of

Ireland’s benefits system which excludes relatively few people. Here a comparison with Greece is instructive:

in 2010 less than 20% of the long-term unemployed were receiving unemployment

benefits, yet over 60% of the jobless poor were not even covered by social

assistance (European Commission 2014: 133).

Two other aspects of state income and expenditure are important.

First, it is perfectly possible for a taxation and benefit system to actually exacerbate inequality. Figure 2 shows how in Poland between 2007 and 2010 inequality of market incomes was reduced, but this fall was much less for disposable income. Consistent with this, Figure 1a shows Poland in 2013 as having a relatively equal distribution of gross earnings, but when actual disposable incomes are used as in Figure 1b Poland moves significantly to the more unequal end of the spectrum.

|

| Figure 2 Change in Gini for disposable and market incomes 2007-2010 Source: OECD (2014: 111) |

Ireland is also a low taxation society - as TASC has repeatedly documented the share of taxation is lower than in most EU states especially in the more developed welfare states. Very simplistically this would seem to suggest that whereas in a country like Denmark the state has enough revenue to redistribute income, and provide services and invest in physical and social infrastructure, in Ireland it can only effectively do the first. Whether this actually is the case would be a useful subject for research and discussion.

References:

European Commission (2014) Employment and Social Developments 2013. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Hearne, Rory and Cian McMahon (2016) Cherishing All Equally 2016: Economic inequality in Ireland. Dublin: TASC

Hills, John (2015) Good Times, Bad Times: The welfare myth of them and us. Bristol: Policy Press.

OECD (2014) Society at a Glance: OECD Social Indicators. OECD Publishing.

Savage, M. et al (2015). The Great Recession, Austerity and Inequality: Evidence from Ireland. ESRI Working Paper No. 499 (April 2015).

Wickham, James (2015) Irish Paradoxes: The bursting of the bubbles and the curious survival of social cohesion. Steffen Lehndorff (ed.), Divisive Integration: The triumph of failed ideas in Europe – revisited. Brussels: ETUI, pp. 127-147.

1 comment:

To a large extent this is merely a restatement of what has been obvious to many people for some time. It is also pretty obvious that proportionately more fiscal resources are being devoted to income redistribution than to the provision of services and investment. It's a little puzzling why this should be a matter for further research and discussion - unless the intention is to distract public attention.

And so it appears to be the case. This curiosity about the scale of fiscal resources being devoted to income redistribution may be contrasted with the apparent total lack of interest in why, among all OECD member countries, the market income distribution is the most unequal in Ireland.

This is treated as some external, exogenous factor over which we have no influence. But the reality is that it is the result of largely publicly authorised rent-seeking and inefficiencies generated by the sheltered private, public and semi-state sectors. And all special interest groups across the political and economic spectrum are skilled at capturing rents and equally capable of generating inefficiencies which impose excessive and unjustified costs on all other citizens and residents.

In other jurisdictions public disgust and anger would restrain the imposition of these excessive costs. (For example in Britain the rip-offs being perpetrated by the Big 6 energy companies provoked sufficient disgust and anger that a two-year long inquiry by the national competition authority was initiated. However, because the authority's proposed remedies do not go far enough, the UK government is developing more effective remedies.) But, in Ireland, a huge share of fiscal resources is used to ameliorate the impact of this rent-seeking and inefficiencies on ordinary citizens.

Occasionally, it's not possible to hide the rent-seeking or to bribe citizens with their own money. The proposed water charging regime gave ordinary citizens a glimpse of how a conspiracy of elements in the sheltered private, public and semi-state sectors intended to capture economic rents, sustain existing inefficiencies and to fatten themselves at the expense of ordinary citizens. The government's panicked response and the resulting over-egged, multi-inquiry and multi-institution package that has emerged from the programme of government is evidence of the determination to conceal this behaviour. (Of course the left and the pseudo-left sought to distract public attention because some special interests that they favoured were also in on the act.)

This publicly authorised rent-seeking is endemic and pervasive. It probably wouldn't take much for another blatant example to be exposed and the disgust and anger of the public to be aroused. It will have to be tackled eventually.

Post a Comment