Friday 30 July 2010

China (III) - Beijing's scramble for Africa

China is Africa's second-largest trading partner after the United States. The continent needs China’ extensive investment to rebuild its failing infrastructure. Chinese companies are replacing Western companies with contracts to build roads, railways, pipelines, hydroelectric dams, and to upgrade ports.

Chinese interest in Africa is direct and indirect; large landholdings, factories, investment and construction of infrastructure etc. For example, China is rebuilding oil-rich but corrupt Nigeria's poor and inefficient railway system. However, China will supply nearly all the equipment and technical personnel, and at prices which it determines. And in line with other projects in Africa, China will supply most of the workers.

China also requires the energy supplies and huge minerals resources of Africa. The comrades in Beijing know that West African oil reserves are a resource that can reduce its dependence on volatile Middle Eastern markets.

The United States and the West are aware of the growing Chinese involvement and investment in Africa. While the United States does not have a colonial past (except as the first colony to break free) as do the major European countries, it is still viewed as the world’s only Superpower today by many in Africa. So the Chinese are welcomed.

U.S. legislation forbids aid for projects that may transfer U.S. jobs abroad, while Chinese aid is actively encouraging Chinese companies in key industries and also to even move factories to Africa. China's aid is often non-transparent, and many investments pay no attention of local interests and ignore local communities.

Ireland’s Tullow Oil is siding with the huge Chinese state oil company China National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC) rather than with US companies. "Our shareholders believe in Africa," its boss, Aiden Heavey says. American investors, by contrast, are still wary and "tend to stick offshore". Tullow grew from nothing into the top third of the FTSE 100 with a market capitalisation of Stg£11.3bn, thanks to two of the biggest oil discoveries of the past decade, remains to a great extent "unexplored". Even last week Tullow found more oil in Ghana.

Tullow is negotiating with France's Total and CNOOC to farm out at least half its assets in Uganda's Lake Albert basin, where it has played the main role in the discovery so far of 750m barrels of oil. The deal would deliver a "hell of a combination", Mr Heavey argues.

"The Chinese will be very helpful in building up other industries and CNOOC is a very attractive option there because the Chinese have proved in the past that they will put the infrastructure in place," Heavey said, adding that Total brings oil expertise, financial firepower and long experience in Africa to the equation.

Chinese companies are also considering the purchase of interests in Nigerian oil companies, including the stakes currently held by major American companies.

Beijing is encouraging Chinese companies to buy great tracts of farmland abroad, particularly in Africa and South America, to help guarantee food security. Concern over food supplies has increased in China, Japan and Russia. Russia plans to form a state grain trading company to control up to half of the country's cereal exports. Cofco, China's state-owned food processing group, is working with Itochu, the Japanese trading company, to buy grain and other agricultural commodities in global markets to build pricing power and so combat rising food costs.

The congested roads in Nairobi are being widened and repaved as "a gift from the people of China.” While the investment will ease congestion for Kenyan motorists, it is really secondary to Chinese interests which require modern infrastructure to move African commodities to ports for shipment to China. It has been reported that China recently purchased half the farm land under cultivation in the Congo!

In Namibia, China established its first overseas military base to track its satellite and manned space flights.

The issue of Chinese involvement is not uncontested, and is turning nasty in parts of Africa. In Nigeria, the Movement for the Emancipation of the Niger Delta (MEND) has said it will expel all Chinese workers in the area. In April 2007, nine Chinese workers were killed in an attack by armed men on an oil field in eastern Ethiopia.

In South Africa, the textile union claims around 100,000 jobs have been lost as Chinese synthetic fabrics replace cotton prints in street markets across Africa and, in 2007, South Africa's unions threatened to boycott anyone selling Chinese products, including on street markets. Rene N'Guetta Kouassi, the head of the African Union's economic affairs department, warned: "Africa must not jump blindly from one type of neo-colonialism into Chinese-style neo-colonialism" (AFP, September 30th 2009).

China is known to work uncritically with some of the nastiest regimes in Africa. It sells arms, jet fighters, and military vehicles to Zimbabwe, Sudan, Ethiopia and, in the UN, China has used its veto power to block sanctions against tyrannical regimes in Sudan and Zimbabwe.

Sudan, with its huge oil reserves, is the largest recipient of Chinese investment. It sells two-thirds of its oil to Beijing. China has been criticised for its links with this government for its role in the ongoing crisis in Darfur.

The working conditions in many Chinese aid-funded projects are poor. Many Chinese developers still see environmental destruction as the price to be paid for economic progress. For example, the Bui Dam will flood a major part of a national park, and will probably generate much greenhouse gases. This dam, in Ghana, is an example of China's resource-backed lending. In 2007, China Exim Bank, the Chinese state import-export bank, approved $562 million in loans for this hydropower project on the Black Volta River. Ghana mortgaged its cocoa exports to access this loan.

China is also investing $1bn in a coal project in Mozambique’s Tete province. Wuhan Iron and Steel, one of China’s biggest steel producers, will spend $200m on an 8 per cent share of Riversdale, an Australian company developing two coalfields there. Wuhan will also commit a further $800m to the Zambezi coal reserve. The coal is one of the world’s largest untapped reserves of coking and thermal coal. Coking coal is used to make steel, while power plants provide a market for thermal coal. Wuhan will buy about 40 per cent of the coking coal produced from Zambezi, and the company will have the right to purchase at least 10 per cent of that produced from the neighbouring Benga project. And another Chinese company will build connecting infrastructure to get the coal to port by barge!

Many Chinese firms employ large numbers of local workers in many projects, but wages remain low. However, there is evidence that African workers are learning new skills because of the availability of Chinese-funded work. Taking advantage of low labour costs, the Chinese are also building factories across Africa. "China consistently respects and supports African countries," Yan Xiao Gang, China's economic attaché in Ethiopia, told the BBC. "It never imposes its own will on African countries, nor interferes in the domestic affairs of African countries."

On the plus side, Africa does well when commodity prices are high, and it is China which has pushed them up, with its huge demand. Poor African consumers like the cheap Chinese goods. Chinese migrant traders are increasingly selling cheap clothes, plastic goods, shoes, and household wares. In many of the smallest towns and the largest cities in Africa, Chinatowns are emerging up, with bazaars selling cheap imports from China. But against this, as African economies continue to export unprocessed goods, its indigenous manufacturing industry fails. And those cheap imports have threatened the collapse of Africa's textile industry, and local manufacturing. Most African countries have now a growing trade deficit with China.

African governments like China's loans which are cheaper and have much fewer strings attached than loans from the IMF or World Bank. Chinese interest in Africa is stimulating other countries and firms’ interest in the continent, and so investors and traders are setting up shop there. China's gifts to modern-day Africa will soon include a major new conference centre at the headquarters of the African Union in Addis Ababa.

In conclusion, China’s interest in Africa brings many benefits to the continent’s 50 states and its peoples, with its huge demand for resources, its investment in infrastructure, and its cheap goods for its citizens. China also gives less tied and cheaper loans than the ideologically-laced loans from the IMF and World Bank. But on the other hand, we have seen that uneven international development means that African industry is threatened, and while workers have jobs and roads, they are being exploited too.

China’s scramble for Africa is an interesting space, with many shades of history repeating itself. In the next post, I shall examine the role of Chinese state companies, just as Ireland’s short-sighted government establishes the Privatisation Board.

Thursday 29 July 2010

The unacknowledged demise of the Government's fiscal strategy

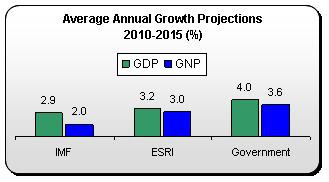

The ESRI presented two growth scenarios for the Irish economy – high-growth and low-growth. In reality, the low-growth scenario is more likely for the simple reason that it is not really ‘low’. It’s lower than the Government’s projections (which have been labelled ‘optimistic’ by the IMF and the OECD) but higher than the IMF estimates. So it’s pretty much in the mid-range.

On the basis of this low-growth scenario, the ESRI says the Government cannot reach the Maastricht threshold – not by 2014, not by 2015 not even by 2020.

• By 2015 the deficit is estimated to be 4.1 percent (not counting any banking subsidies)

• By 2020 the deficit is estimated to be 4.5 percent

In addition, they estimate our overall debt levels will be 102 percent of GDP in 2015, rising to 106 percent five years later.

The reason the deficit and debt start rising after 2015 is because the ESRI estimates that real growth will start to ease off, falling from an average 3.2 percent over the next five years, to 2.1 percent afterwards. On this basis, we would have to cut the deficit to well below -3 percent by 2015, just to ensure we don’t rise above it again in a few years. They summarise the problem:

‘The lower level of economic activity would reduce government revenue from taxation while the higher unemployment rate and borrowing would increase government expenditure on welfare payments and interest payments. This would result in a significant deterioration in the general government balance . . ‘

So why, according to the ESRI, would this state of affairs come about? They first assume the economy won’t respond to increased world growth as robustly as in the past. But they also point out that a poorly functioning banking system, higher cost of capital and structural unemployment could also contribute to a low-growth scenario.

What they don’t mention is the impact of the Government’s deflationary cuts - which is strange since they point out that the Government’s €3 billion fiscal contraction in the 2011 budget will cut economic growth (by approximately 1 percent – though this was before the Government’s announcement that spending cuts, which are more deflationary, will play a more prominent role in the composition of the contraction).

It is even stranger since they have just released a revised set of fiscal multipliers, updating their paper from last year. These updated multipliers show that they previously under-estimated the impact of spending cuts on economic growth:

• A €1 billion cut in public sector wages will reduce GNP by 0.4 percent (previously it was 0.3 percent)

• A €1 billion cut in public sector employment (about 17,000 jobs) will reduce GNP growth by 1.0 percent (previously t was 0.9 percent)

These might seem marginal but given the scale of cutbacks the Government (€2.4 billion in pay cuts, €3.6 billion in non-wage consumption, €2.6 billion in investment cuts), it all adds up.

The key metric is employment and this, more than anything else, helps explain the low levels of growth and, so, the failure of the Government’s fiscal policy. The ESRI estimates that employment will grow by an average 1.3 percent between 2010 and 2015. This compares to the Government’s estimate of 2.0 percent average.

Again, this might not seem much but add it up. But by 2015, the ESRI is estimating we will have approximately 70,000 fewer jobs than the Government’s projections. When you factor in the impact on tax revenue, unemployment costs and the significant social costs of long-term and structural unemployment – you start to see why the Government’s fiscal strategy will fail.

None of this should come as any news – if we were fortunate to get the news: the IMF similarly projected the Government’s fiscal strategy will fail. So, too, did the Ernst & Young / Oxford Economics report (though they held out hope that the deficit might come under control by 2018/2019 – but only at growth rates that exceed the ESRI’s estimates).

Of course, some might be tempted to say, that after nearly €9 billion of spending cuts with the prospect of billions more planned, all we need to do is cut just that little bit more. Just dig a little deeper and we’ll get out of the hole. But that’s the problem – every new estimate, every new projection tells us that fiscal consolidation is getting further and further away the more we cut. How much longer do we go along with this ‘Boxer mentality’ in the face of an emerging consensus that the Government’s strategy is flawed at its core; that no amount of tweaking will rescue it. Indeed, further cuts, in addition to what the Government is planning, will only undermine economic and employment growth even more. What will we do then? Call for even more cuts? How deep does the hole have to get before we stop digging?

So what have got? Low growth, escalating debt, high unemployment and emigration, sluggish economy – and the failure to repair public finances; if the ESRI buried the Government’s fiscal consolidation strategy, it also buried the McCarthy report. You probably didn’t hear about that either.

That’s why my next post will deal with that.

Evolution ... and economists

Michael Casey, reviewing The Company of Strangers: A Natural History of Economic Life (Business, July 26th), reads that evolutionary theorists believe the murder of 20 million Congolese by Belgian colonists was not down to imperialism but due to an evolutionary failure to develop sufficient trust in strangers. And yet the remainder of that day’s business pages are replete with the most touching examples of misplaced trust. We learn from Wolfgang Munchau that the strategy behind the recently completed stress tests (grade inflation for banks) was premised on the assumption of an innocent trust in the results by investors and the public, validated apparently by your reports of a positive response from “the markets”.

We are informed by Tony Jackson that pension funds are still too trusting of the private equity industry despite a report on the opposite page that this industry has “underperformed stockmarkets, taken excessive risks, and overcharged investors”. We find out that despite rising losses at Aras Sláinte, “the group continues to have the solid support of its bankers and shareholders” (one of whom is reported to be a private equity firm associated with Anglo-Irish bank). Speaking of Anglo-Irish bank, we find that after the NAMA process, it lent a developer a further €25 million and entrusted him with a line of credit for over €353 million. Still on NAMA, a survey finds that 66 per cent of Irish chief financial officers think NAMA will improve credit availability.

Finally, in what is perhaps the most moving example, we are told that, in response to queries over royalty payments to executives, director Ivan Yates is reassured because management has said its lawyers and auditors approved the controversial payments. According to the scientists, all of this would seem to violate basic human nature. On this evidence, evolutionary psychologists would appear to be no more worthy of trust than say . . . economists.

Tuesday 27 July 2010

The Austerity Debate

Minimum wage - facts, fiction and flights of fancy

It was in that context that TASC made a presentation to the Oireachtas Joint Committee on Enterprise, Trade and Employment on ‘The Minimum Wage’. TASC’s evidence demonstrated that any reduction to the minimum wage would exacerbate the deflationary situation and have a negative impact on the public finances. In the media debate following TASC’s submission, the business lobbies focused on the cost of the minimum wage and how it is ‘unsustainable’, ‘preventing businesses from hiring’ and ‘a major contributor to a loss in competitiveness’. Once again, it’s important to identify the facts from the fiction in relation to the minimum wage and to look at the latest evidence on competitiveness.

Despite what you may read or hear, the minimum wage rate is not the second highest in Europe for the following reasons:

1. First, when comparing minimum wages across a number of countries you can only do so by taking the Purchasing Power Parities into consideration i.e. calculating how much you can buy with your minimum wages. This is done by expressing the minimum wage in terms of a common unit called the Purchasing Power Standard (PPS). When expressed in PPS terms, Ireland’s ranking drops from second to sixth place, reflecting our higher cost of living. Ireland’s monthly minimum wage is €1,152 in PPS. The UK is in fifth place with a monthly minimum wage of €1,154 (in PPS) and France in fourth place with a monthly minimum wage of €1,189 (in PPS)(details here).

2. Second, Eurostat data calculates wages per month. Ireland’s monthly rates are calculated on the basis of a 39 hour week, France on the basis of a 35 hour week and the UK on the basis of the 38.1 hour week. If we differentiate for the number of hours worked in the three countries we find that the hourly minimum wage is €7.84 (PPS) in France; €6.99 (PPS) in the UK and €6.82 (PPS) in Ireland.

3. Third, the data only refers to those European Members that have statutory minimum wages. This means that the dataset does not include the Scandinavian countries. Collective bargaining is used to set minimum wages in these countries and an October 2008 study by Swedish economists showed that Sweden, Finland and Denmark all had higher hourly minimum wages in 2006 than Ireland, as did Norway which is not a member of the EU.

4. Eurostat also calculates the minimum wage as a per cent of average monthly earnings. The minimum wage in Ireland was 42 per cent of average industrial earnings in 2008, which puts Ireland in ninth place in the EU, or in twelfth place if we include the corresponding 2006 percentages for the Scandinavian countries

When calculating the cost of employing a person, it is more accurate to look at the overall cost of labour which is made up of labour and payroll taxes (PRSI). Ireland has one of the lowest levels of employers’ social protection contribution in the OECD. The Irish rate (10.8 per cent) is significantly lower than the OECD average (15.2 per cent) and the euro area average (27 per cent), which reduces the total cost of employing workers in Ireland. The hospitality sector is the largest employer of low wage workers and labour costs in Ireland in this sector are the third lowest in the EU 15. Only Greece and Portugal had lower costs per employee than Ireland.

When we look at the facts in the cold light of day it is clear that the minimum wage is not out of step with other European countries and when we consider the total costs of employing people, Ireland is indeed very competitive. However, if the minimum wage is causing serious problems for businesses, surely it would be highlighted in any analysis of competition?

Last week the National Competitiveness Council published its annual report on competitiveness for 2010, and it demonstrates that the minimum wage is not a factor impacting on business’s capacity to survive the current challenging trading environment. They found that Ireland’s cost competitiveness has improved considerably for a range of key business inputs such as energy, property and a number of business services. However, the areas where key inputs in Ireland remain relatively expensive include broadband, waste disposal and legal fees. There is no mention of the minimum wage being prohibitive for business ... and in fact the report found that “Irish salary levels are broadly in line with the euro area average across the benchmarked occupations”(p.22.)

Business lobby groups have also been arguing that the minimum wage is preventing them from hiring, and that the costs associated with hiring minimum wage workers is putting business under pressure. This argument is not supported by a single shred of evidence. In fact, the evidence supports the opposite – that the minimum wage has little or no impact on employment. David Metcalf at the London School of Economics undertook empirical research and a wide ranging review of the literature in 2007 and found that the British National Minimum Wage has little or no impact on employment (see also here).

There is no doubt that the recession has impacted on businesses and has led to many businesses having to close their doors and cease trading. However, these difficulties have not been caused by the minimum wage. Factors such as access to credit, high commercial rents, professional fees, waste charges, the price of food and the collapse in demand, in particular, have had a devastating effect on the SME sector. These are the factors that need to be addressed to support businesses in these difficult times – rather than an unsubstantiated attack on the lowest paid workers in our economy.

Monday 26 July 2010

Selling the family silver: bad for the economy and citizens

The plan is to raise billions for the state coffers from the sale of many of these companies. The hope is that this could be set off against the projected exchequer deficit of €26 billion for next year and the national debt which now stands at €84 billion. Many of these companies are indeed valuable. The values put on Bord Gais and ESB are €3.5 and €5 billion respectively.

However, it would be a serious mistake to sell off these state owned enterprises. The proposed sales are a smash and grab exercise aimed at raising quick money for the government without any real consideration of the consequences. The problems which the sale of Eircom continues to cause for the Irish economy highlight the dangers of privatisation.

The sale of Eircom raised €8.4 billion for the government but has done untold damage to the competitiveness of the Irish economy: the company has been bought and sold several times, and has had four different owners in recent years. The sale has resulted in the company not been able to develop its broadband infrastructure to anything like the level which is required in the modern business environment, and this has hampered the development of high speed internet in Ireland ever since.

In the aftermath of the various sales of the company in the hands of ruthless venture capitalists, it now owes nearly €2 billion. Previously it owed very little. It has also started to shed considerable numbers of workers and has only limited ability, as a result of its debt, to finance the rolling out of high speed broadband.

The privatisation of state enterprises is based on an ideological position which assumes that private companies achieve higher levels of performance than state owned enterprises. However, a study of companies privatised by the Irish government from 1991 to 2003 by Reeves and Palcic (2005) found no evidence for this assertion. They also found that shareholders and employees who receive 15% of the shares tend to be the main winners in privatisation, not the government.

Perhaps one of the most compelling arguments against the sale of State Owned Enterprises is the loss of national control overall in hugely strategic areas which determine our economic viability and competitiveness. If the two largest energy producing companies where sold to private investors, industry and consumers could end up being at the mercy of super-profit-seeking business owners which could drive up costs and make Irish businesses uncompetitive. At present, the government by way of the energy regulator can control the price of energy.

It is precisely due to super-profit-seeking privately owned businesses controlling goods and services that should be kept in state ownership, that health care is so expensive in the USA. There, private Health Management Companies (HMOs) own most hospitals and charge exorbitant fees. The result is that basic health insurance is at least 800 dollars a month per person in the USA. The same argument can be cited to oppose the privatisation of the countries ports, RTE and others. It has been reported that Ruport Murdoch is interested in purchasing RTE. In that event, once in an almost monopoly position, the cost of TV viewing would be likely to rise significantly.

The sale of ports would put the country at a huge strategic disadvantage. The UK government in recent years has privatised its ports for a return of 6 billion and has sold the London-based Thames Water company for 9 billion. If Ireland were to sell its ports and its domestic water infrastructure, it is likely that these utilities would be run as public-private partnerships (PPS). These are exceptionally costly for the state and the taxpayer in the long term, and it is likely that hefty charges for water and the use of ports would ensue to the hardship of consumers and the disadvantage of businesses. One might also argue that the loss of ownership and strategic control of a country’s ports strongly compromises national sovereignty.

Also, in Ireland at present, the ESB is responsible for integrating its supply grid with that in Northern Ireland in a move towards closer economic co-operation, which was been lauded only this week by Northern Ireland’s Deputy First Minister Martin Mc Guinness at the Magill Summer School. If the ESB were owned by private shareholders, there is no guarantee that this would happen.

Of course, the biggest problem is the loss of employment. In the wake of the privatisation of ACC Bank and Aer Lingus (amongst others) since 2005, the Central Statistics Office has shown that the numbers employed in state owned enterprises fell from 57,400 to 52,300 by 2009, a loss of 5,100 jobs, which the CSO attributes mainly to privatisation.

The privatisation of Bord Gais, ESB, An Post and other semi-state companies would result in a dramatic downsizing of the workforces in these companies. At a time when unemployment stands at 450,000 and where the government is content to sit out the recession without stimulating the economy, the prospect of the state itself putting thousands or even tens of thousands people out of work, due to privatisations, would seem to be unthinkable.

Interestingly, it is the opposite course of action which is now being proposed in the global post-financial meltdown world: Prof. Aldo Mustacchio of Harvard Business School has written several papers in the past two years in which he highlights the need to use state owned enterprises as vehicles for employment creation and to help significantly in national economic recovery.

Many large state owned enterprises have been performing exceptionally throughout the world, he says, from the state owned oil company Petrobas in Brazil to Statoil in Norway and the State owned Gazprom company in Russia. There are many other companies in other economic sectors also in countries such as Singapore and India. The mistake in Ireland has been to allow private interests to take control of valuable natural resources with no return to the exchequer. The case of the Erris gas field in Mayo, which was essentially given away free of charge by then Minister for Energy, Ray Burke in the mid 1990s, is a case in point.

However, it would be a mistake to think that new state owned enterprises would be flabby and inefficient which many politicians and economists from a right-wing persuasion would have us believe. There is a future for lean and competitive state owned enterprises in Ireland where performance and productivity would be high and where performance management systems would predominate.

State owned companies of this type have existed in Sweden for many years. At present there are 55 state owned enterprises in Sweden. In 2006 these companies turned over 50 billion and generated net profits of 8 billion for the exchequer.

It is for these reasons that any hasty attempt by government to sell the family silver in an ill thought out and hasty fashion to reduce indebtedness should be strenuously opposed by Irish society.

This piece first appeared in the Irish Examiner

Stimulus and austerity

Up to now there has been no debate. Part of the reason is that it’s extremely difficult the get the pro-stimulus arguments into the public domain. Those who comment on economic issues in the national media almost all subscribe to the ‘fiscal austerity’ consensus. Those who put forward the pro-stimulus position are routinely dismissed as not understanding the gravity of the State’s fiscal position or promoting narrow sectional interests. During the week, Paul Krugman bemoaned the quality of economic discourse on both sides of the Atlantic. In Ireland we should be so lucky to have the kind of discourse that’s taking place in the US and the UK, for example! So, in that context we should welcome the engagement that’s taking place between Karl Whelan, Michael Burke and Michael Taft on irisheconomy.ie. It’s a start.

What’s less encouraging is the content of the interview given by Eamon Gilmore on the Pat Kenny show last Monday morning. In the interview, Gilmore firmly nails his colours to the mast by affirming the Labour Party’s support for a €3 billion fiscal contraction in the forthcoming December budget. He goes on to express support for the government’s stated target of reducing the deficit to less than 3% of GDP by 2014.

On the latter point, this seems an ill-advised position for a prospective Taoiseach to adopt. If, as most progressives hope, Gilmore is Taoiseach after the next election, then his stated commitment to meeting this 3% target may be one he regrets making as most independent commentators now accept that Ireland has little prospect of meeting it in 2014. The IMF recently predicted that our deficit will be 5.9% in 2014 (see page 30 of the report). The Ernst & Young / Oxford Economics survey suggests we won't reach Maastrich compliance until 2018/2019. Further, two days later the ESRI report (see page 79) implied that additional fiscal contraction beyond that already planned by the government would be required to meet the 3% target.

From a policy point of view the realistic (and sensible) thing to do is set this 2014 – 3% straightjacket aside. That opens out the debate and helps focus on the fact that the deflationary policies pursued to date are strangling the domestic economy and suppressing the growth in revenue which has to be part of any solution that addresses the deficit in the medium term.

Eamon Gilmore’s stated support for a €3 billion ‘fiscal correction’ in the December budget is even more unfortunate. In fairness, in the interview he indicates that the €1 cut in the capital programme would be supplemented by funds from the Strategic Investment Bank the party proposes to establish (hardly realistic in the context of the December budget) and part of the cut in current spending would come from the reform of property and pension tax allowances. Unfortunately, in terms of the public discourse on macroeconomic policy, these details will receive little prominence. By supporting the €3 billion fiscal correction, the Labour Party ends up being co-opted on to the side of those arguing that there is no alternative to fiscal austerity. The result is that the range of ideas that gain prominence in the public domain is reduced, and we end up with an even more lop-sided debate on how to solve our problems. The consensus reigns.

Saturday 24 July 2010

The Economics Anti-Textbook....at last some fresh thinking on economics

It also includes a series of thought-provoking 'questions for your professor' throughout; such as "Why does the textbook suppose that democracy must end at the workplace door? In whose interest is it that economic democracy remain off the agenda?' and "The competitive labour markey model predicts that if a firm reduces its wage by one cent below the equilibrium its entire workforce will quit. Why don't we test this prediction?"

The book also includes a postscript on the global financial meltdown which as they put it "illustrates the importance of imperfect and assymmetrical information, externalities, limited rationality and inappropriate incentives. In particular, it illustrates the necessity of appropriate government regulation, and the ability of powerful business interests to change the rules of the game" .

Wish I had had this textbook when I was an ungraduate!

Friday 23 July 2010

The Privatisation Board: What will it do?

The same procedures used in producing the McCarthy/Department of Finance report will likely be followed in this new report. Officials in the Department of Finance will draft chapters, proposals and conclusions which will be largely accepted by the Privatisation Board.

Who is driving these policies?

These recommendations are likely to be as already described. The reason for this is that prevailing IMF views are largely held within the Department of Finance. While privatisation was not a policy recommended by the recent IMF Article IV consultation, the report in several places acknowledges IMF staff agreement with “the authorities” (not defined but referred to elsewhere as “the officials of Ireland” and also states the IMF report also states that meetings were held with senior officials from the Department of Finance, etc.). The IMF together with the World Bank helped establish privatisation as part of the Washington consensus, often with disastrous policies for developing countries. These discredited policies are now being reintroduced as conditions for IMF loans to countries with large budget deficits such as Greece.

Why privatisation is not a solution

Privatisation largely involves an exchange of ownership. The State will obtain financial assets in exchange for real assets. These financial assets could be invested in other real assets, but this is unlikely, rather Government borrowing/debt will be reduced. This exchange will be costly. Firms such as Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch, PricewaterhouseCoopers, Arthur Cox, etc.(all featuring in advice to the Government in relation to the banking crisis) will again be paid large fees. Apart from the cost, privatisation is no solution to Irish economic problems. The States net Balance Sheet remains the same, but the policies privatised companies may pursue will be very different. Some firms such as the ESB are natural monopolies. Regulation is key - an area where Irish agencies have a particularly poor track record. State control of monopolies can address deficiencies in regulation. What about commercial policies? Paul Sweeney has argued coherently that commercial policies of formerly State owned companies have been disastrous for Ireland’s economic success the best known is Telecom Eireann. But policies pursued by other privatised firms have added to the economic crisis for example the former ICC and ACC banks. The operations of the former Irish Sugar company (Greencore) are now focussed largely outside Ireland, and as such are unlikely to contribute to the development of agribusiness within Ireland as recently expressed in the 2020 Food Harvest Report.

In the current crisis we have been badly let down by former and current employees of the Central Bank, the financial regulator, those who designed and encouraged our gross over reliance on tax incentives, those in charge of our planning process, but in particular by institutions largely in the private sector, banks, building societies, professional firms such as auditors. Corporate governance has not been an issue in Commercial State Bodies in contrast to private sector firm such as Banks, the Quinn group, and DCC. The solution is not more economists with their misguided views on ‘efficient markets’, and ‘rational behaviour’. Banks in recent years have lost billions, competition policy as implemented by the EU Commission has lost billions more. Nor is the solution privatisation.

Arguments against privatisation are compelling. It is important that they are expressed.

Leprechauns, fairies and Professor Fitzgerald's response

Thursday 22 July 2010

Having a go in the dark

The story is probably close to the mark when comparing high-end professionals – the consultant doctors etc.; there is some data to show they are paid above European norms. Of course, this is part of a general story – in both the private and public sector – of phenomenally high-pay at the upper ends which distorts averages. This is why Ireland compares so badly to other EU countries in wage equality statistics. So there’s not a whole lot new there.

The story goes on to quote health statistics from the OECD Health at a Glance reports which, in the words of the OECD itself, should be ‘interpreted with caution’. And for good reason. Let’s look at hospital nurses pay in the 2009 publication. First, this does not measure hourly labour costs – which is the true determiner of cost to the employer; in the case of public sector employees, the Government. Second, it doesn’t compare like with like. For instance, data sources vary from country to country (some include private sector, some include part-time, some include non-hospital staff, some omit certain grades, etc.) – reflecting a real problem in making comparisons that can stick.

Third – and this is a problem throughout OECD wage statistics – most data is compiled on the basis of taking the total amount of wages and dividing it by the total number of employees to get, as they put it, ‘the average gross annual wage’. However, this can be highly misleading. Take this comparison from the EU Klems database (which does measure hourly labour costs).

• In Ireland, annual employee compensation (including non-wage costs) was €44,800 in the whole economy in 2007. In the Netherlands, it was €37,750. On that basis you’d say – wow, we are really high paid compared to the Dutch.

• However, when hourly labour compensation is examined we find the situation reversed. In Ireland, hourly labour costs were €24.82; in Netherlands it was €28.08. What accounts for this discrepancy?

Simple: the Dutch work less hours per employee. In 2007, each Dutch employee worked, on average, 1,344 hours per year; the Irish worked 1,805. Not only is the average working week lower in the Netherlands, there is a higher level of part-time workers.

So if you compare average annual incomes you’re likely to fall into this mistake. So when the OECD puts nurses’ average annual income in 5th place among countries surveyed (including low income Greece, Mexico and the Slovak Republic), it only tells us so much.

Where the OECD methodology is more helpful is when it compares one set of workers with another set in the same economy, since the measurement is internally consistent When this is done, it shows that Irish nurses’ making the same as the Irish average wage – which puts them 15th out of 19 in terms of intra-national comparisons. In other words, in 14 countries nurses make more in relation to the average wage in their own country. On this comparison, Irish hospital nurses are not raking it in.

So is there somewhere we can go to find a robust international comparison of labour costs in the public health sector? Unfortunately, not yet; though the OECD is trying to establish an internationally agreed base-line. However, we can turn to the EU Klemsto find a story that the Sunday Business Post might wish to investigate; though I suspect if they dug too deeply it might lead them to a politically unpalatable conclusion (unpalatable for them).

Hourly labour costs in the Irish health sector were €34.57 per hour in 2007; in the Netherlands it was €25.84. This, again, might lead us to conclude that Irish public health sector workers are, indeed, costly.

But there’s an odd trend here. In 2000, Irish labour costs in this sector were €19.74; in Netherlands it was €20.51. What explains this extra-ordinary growth and turnaround? Of course, we can always put it down to greedy public sector unions, benchmarking, milking the taxpayer, etc. However, this simplistic explanation doesn’t add up.

Given that all public sector workers were covered under the same wage agreements, the same benchmarking deals, we should – according to the greedy-public-sector-worker thesis – expect to find similar increased costs in the Public Administration sector. Except in that sector (which employs a third of all pubic sector workers), nominal hourly labour costs increased by only €6.29 per hour compared to health sector costs which increased by €14.65 per hour.

How could this be? The problem with measuring labour costs in the health sector is that 45 percent of labour is in the private sector. Unfortunately, we don’t have a breakdown between public and private health sectors. But what we may be seeing is substantially increasing labour costs arising from the costly, socially perverse and economically inefficient interpenetration of the public and private in what should be a free and public good. In other words, if public sector health workers’ labour costs have increased in the same manner as other public sector workers, the issue doesn’t lie in the public realm.

It’s hard to know; and that’s the problem. Labour costs in the Public Administration sector is lower than average Eurozone costs; ditto for the Education sector. But the health sector – which is split between public and private – significantly exceeds Eurozone averages.

We do know that of those private sector health enterprises which granted wage increases in 2009, the average increase was 15 percent; for public sector health enterprises it was 7 percent. In the heart of the recession, incomes in the private health sector were rising faster than those in the public sector (though we don’t know that nurses pay was rising this fast in the private sector).

And we do know the EU/CSO shows that between 2003 and 2008 the top 10 percent households took 73 percent of the total gross PAYE income increase in the State. Not only is Ireland suffering from wage inequality, it is getting worse – and I suspect that, public or private, not too many nurses feature in the top 10 percent.

Here is a real story – costs are increasing in public services where the private sector is playing a significant role; and income is rising faster in households which have a disproportionate number of high-end professionals. The Sunday Business Post might want to investigate this further. But I will give them this warning.

They might have to conclude that we need a truly public health sector where goods are delivered, not on the ability to pay, but on need; and we might have to do something about those high incomes.

In the meantime, for want of any analysis that goes beyond dubious headlines, repeat after me: ‘Surely, gosh, we have the highest paid public workers in the whole wide world.’

Wednesday 21 July 2010

Leprechauns and Confidence Fairies

He writes: "The authors simply assert that more austerity now would lead to a lower risk premium and hence higher growth, based on no evidence I can see. They don’t even offer any quantitative assessment of the extent to which more austerity while the economy is still depressed would reduce future debt burdens."

Who needs higher education anyway

Two issues to start with...

Firstly, teaching standards - In the last few decades academic careers have become more international and more firmly based on relatively narrowly defined publication criteria. Notoriously therefore, academics have few incentives to teach well and even fewer incentives to contribute to the wider society. Please note what I am saying here: ‘few’ does not mean ‘none’ and some universities are beginning to tackle these issues. However, the international ranking schemes not only weight the quality of undergraduate teaching much lower than research, but they also use much vaguer definitions. Of course, we academics claim that we should be left to regulate ourselves, but bankers and Catholic priests have said the same thing...Putting money into universities may achieve other objectives, but by itself it won’t do much for undergraduate education. It may actually make it worse.

Secondly, who gets taught - In an era of mass higher education, universities are increasingly differentiated: there are elite universities, there are not-so-elite universities, there are mere universities. There are also significant international variations in the range of these hierarchies. The gap between the top and the bottom in the USA is probably much greater than anywhere in Europe, with the possible exception of the UK.

This is tied up with the role of higher education in the reproduction of inequality. Very crudely, there appears to be a linkage between growing income inequality in the USA since the mid-1970s, the slow-down in social mobility rates, and the extent to which graduates of elite universities increasingly dominate the best paid jobs.

It’s arguable that in the decades immediately after World War II higher education contributed to greater social equality in the USA and in Europe. It’s extremely debatable whether this is now the case. Certainly as far as the USA is concerned, higher education is now part of the problem of growing social inequality. And please notice, higher education in the USA is much more market-based than in Europe...

TASC presentation on the Minimum Wage

Tuesday 20 July 2010

Out of the traps and into the abyss

The journalist goes onto to argue that the downgrade was subsumed by the latest twist in the saga of NAMA, the banks and the property speculators- who want to be bailed out but to keep all their assets too.

But the muted reaction may also have something to do with self-delusion. Mark Fielding of ISME is quoted in the piece as saying that the government is going in the right direction. And there is this quote from the financial journalist Simon Carswell, "The main story here is our problems are huge, but we are doing the right things to fix them. What Ireland has done better than any other country is that it was the first out of the traps to try and fix things. Darling and Brown went in the completely opposite way. They thought they could spend their way out of the recession."

Yet, the British economy did indeed come out of recession, and it was entirely due to increased government spending. The domestic economy expressed by GNP recovered in Q4 2009, at the same time as GDP rebounded. Government current spending and government investment rose by a combined £10.36bn during the British recession, which is greater than the £9.65bn in the recovery to date. Apart from declining imports demand, it was the only category of the national accounts which made a positive contribution to growth in 2009.

Surely, though, spending like this would have produced a huge widening of an already large deficit? By happy coincidence the British ONS also published today the June report on Public Sector Finances. And the short answer is No. In the period since the beginning of the Financial Year, the April-June 2010 public sector net borrowing is £4.6bn lower than in the same period a year ago. And the reason is that taxes are higher, up £9bn. The rolling 12-month borrowing total is down to £143bn. That's just 6 months after the Pre-Budget Report projected a £178bn for this Financial Year.

How can that happen? How can increased government spending lead to a declining public sector deficit? It's actually based on a simple lesson, painfully learnt in the 1930s, after a prolonged period of austerity measures failed to close the deficits. In a slump increased government spending increases total demand, thereby increasing taxation revenues and decreasing welfare expenditures. In short, government spending more than pays for itself- it provides a positive net return to the exchequer. And the opposite is the case; decreased government spending in a slump depresses total demand and so lowers tax revenues and increases welfare payments (even when welfare entitlements are cut).

Irish government policy was first out of the traps- and headed straight for disaster. The British, being relatively slow learners, are now emulating Dublin's policy and will reap the same dubious rewards.

Guest post by Michael O'Sullivan: Who's fooling whom?

It is true that economic data suggest that output in our economy is beginning to recover from the steepest drop that any developed world economy has suffered since the Great Depression and this is very welcome.

What is not true however is that we in Ireland are going to experience a normal economic recovery along the lines of text book business cycles. The danger is not only that our politicians would try to convince us that this is the case, but that they fall for the same confidence trick themselves.

The apparent rationale behind 'talking up the recovery' is that by creating a sense of confidence, consumer and investment spending will follow. This 'if you say it, they will come' approach to economics is absent from most good economics textbooks, and utterly misplaced in an economy where the banking system is broken, government finances labouring under the burden of the banking sector bailout and where there has always been a puzzling lack of commitment by Irish savers to Irish entrepreneurs and industry.

Instead of talking about recovery, our policymakers and politicians should talk of repair, reform and restructuring. Addressing the policy making errors of the past and preparing for a dramatically changing world economy would be the ideal way forward.

Ireland's economy is in many ways an adolescent one. It is not yet fully developed, especially in terms of having a set of robust domestic sectors that can drive growth independent of the global economy.

As such the lesson from the catastrophe of our economic collapse is that we need to reform policy making in Ireland, build new institutions to replace the 19th and 20th century ones that we have in place, resist the temptation to talk about fashionable economic trends like the green economy and focus instead on developing domestic industry and services. What would be even more desirable would be a core set of values that could act as a guide to how society, public life and the economy should interact.

Instead, I suspect most of our leaders will find it easier to close their eyes, avoid the lessons that the financial crisis holds for us and mumble the 'recovery' mantra.

In economic terms the danger of this is huge because absent a magical pickup in household demand (which has rarely occurred in the context of such high borrowing levels) the result will be deflation and ongoing depression.

This is not scaremongering but a warning that the Irish economy needs radical surgery. Even in the large economies of the world the debate leans towards the need for government spending to continue to stimulate growth. The state of our finances means we don't have this luxury, but it also implies that structural reform is the only way we can really recover.

Talking up a recovery is not a strategy. The recent downgrading of the NAMA business plan and the Moody's government debt downgrade should be a warning that things are not as rosy as our politicians suggest. The great risk is that they continue to look the other way.

Michael O'Sullivan is the author of Ireland and the Global Question, and co-editor of What Did We Do Right? Global Perspectives on Ireland's Miracle, recently published by Blackhall Publishing

Monday 19 July 2010

Between the rocks

Never before have statistics been so cruelly tortured to find inflection points and decelerations in the rate of decrease and positive signals from one Quarter’s data or one month’s data as if trends were linear and smooth (note that the statistical requirement arbitrarily used by some analysts to see two consecutive quarters of growth to announce a recovery has been left aside as GDP growth in Q1 of 2010 was enough to spin the story).

One of the aspects of being caught between a rocky hard place and a hard place is that the rocks have been arranged and the thinking arteries hardened so as to avoid any consideration of alternatives. Instead, we have the delusional recovery by a 1,000 cuts. But, the cuts agenda is running into trouble on three counts:

The underlying parameters (leaving aside Anglo which is a mighty big elephant in the fiscal parlour) are not shifting south rendering the 2014 SGP looking like the Emperor without a leaf.

Rising unemployment and contracting income are driving up some of the fiscal stabilisers such as eligibility for medical cards, unemployment welfare and other ‘automatic’ payments.

The politics of cutting again by some €3bn and then again by some equal amount in Election Year minus one look increasingly problematic.

Here’s the story:

1 Public sector pay bill (around 30% of total public spending) is pretty much pegged for the next three years unless there is some ‘unexpected deterioration’ in public finances.

2 Government is moving at snails pace to reform taxation especially in those areas where the rich gain the most (property, tax breaks and financial transactions). The promise of economies through changes in work practices doesn’t translate into lower public spending. Such changes in practices and greater flexibility might enable – over time – a better quality and quantity of public service (however measurable) for a given input of persons or money. It might even enable Government to – eventually – reduce spending by employing less staff in the key sectors (health, education and central/local government for a given outcome of public service). My bet is that:

* Numbers employed will grow in some areas and stagnate or fall a little in others

* The (nominal) pay bill will rise very slightly due to automatic increases (e.g. increments) as well a structural changes arising from the shedding of low-paid and low-skill jobs over time (just watch which vacancies are being filled).

* ‘quality’ improvements in service will be glacial

* Grass-root pressure will build up to revisit the terms of the nominal pay freeze especially as GDP starts to grow and prices erode real wages.

3 The Greens have – for now – taken ‘free fees’ and further changes to the staff-student schedule at primary and secondary level education off the agenda. That’s a lot of cash.

4 The banking tragedy (farce?) looks fearsome – with a roll over of debt bunched to maturity at end of September 2010 and with continuing pressures on the banks a fresh round of recapitalisations cannot be ruled out (thus pushing the measured General Government deficit to over 20% in 2010 and possibly 15% plus in 2011).

The counter-factual of ‘doing nothing’ – i.e. not following the deflationary line since 2009 is adduced as reason to stay the course and continue cutting more. Yet, nobody has shown, empirically, what would have happened if Government had adopted a different growth strategy and made different choices. Everything is predicated on static zero-sum analysis.

The choice of deflation (and it is a choice) leaves Government with some pretty stark new choices within its medium-range deflationary strategy:

- More cuts to an already crisis-ridden health system

- Amputations to significant public service programmes in local authorities and central government (you can guess which)

- Larger deflationary measures than those spoken of to date.

- Revisiting the Croke Park deal

- Further cuts in social welfare targeting this time older folk and children (so much for the fine sentiments behind the proposed Childrens’ Rights referendum)

- An IMF-EU rescue plan later on

- An early election

Take your pick.

Fancy being in the opposition benches? – supporting the broad parameters of the fiscal contraction and yet hedging bets on just how these cuts would be implemented and which taxes would be raised if one were in Government.

Some day, the case for a sane, investment strategy to grow our way out of this fiscal, banking and human skills utilisation hole will become inescapable.

Costly Business: Privatisation and Exchequer Revenues

It appears that the principal rationale for any potential privatisation is to raise revenue for the exchequer in order to deal with the country’s acute fiscal crisis. Although privatisation can raise useful revenues for the exchequer in the short- to medium-term it cannot, however, be justified on this basis alone. In a recent article published in Administration, we show that the revenues generated from privatisations, both in Ireland and abroad, are rarely maximised.

In Ireland, ten SOEs have been privatised to date and the exchequer has accrued over €8.3 billion. However, we show that the exchequer has foregone over €2.1 billion as a result of a combination of costs related to the underpricing of shares, debt write-offs, fees to advisors, underwriters etc., and the establishment of employee share ownership plans (ESOPs), which account for approximately half of the foregone revenues.

This is shown in the table below, where direct costs refer to advisory fees etc, and indirect costs refer to the cost of debt write offs and the underpricing of shares. Admittedly, the aggregate costs are dominated by the biggest divestiture to date (Eircom), however, there were questionable decisions in relation to a number of other sales. For example, when the refinery and terminal operations of the Irish National Petroleum Corporation (INPC) were sold in 2001, the sale involved a large debt write-off and other costs which amounted to €76 million. The Whitegate and Bantry assets were sold for €116 million, but six years later the new owners put the Whitegate refinery up for sale for a price of approximately €350 million.

The cost of ESOPs in the table above is calculated as the difference in the revenues received by the exchequer for the 14.9 per cent transferred to employees and the value of that stake based on the sale price of the firm. For example, in the case of the TSB, employees received a 5 per cent stake in return for accepting a transformation agreement, and purchased a further 9.9 per cent stake for €25.15 million. Based on the €430 million price paid by IL&P for the TSB, the 14.9 per cent stake was worth just over €64 million.

In the case of Eircom, employees also received a 5 per cent stake in exchange for the acceptance of a transformation agreement, and purchased a 9.9 per cent stake for €241 million. Based on the proceeds from the flotation of the government’s 50.1 per cent stake in July 1999 (which raised €4.2 billion), the 14.9 per cent stake transferred to the ESOP was worth approximately €1.25 billion. The difference between the amount received by the exchequer for the 14.9 per cent stake and its actual value amounts to over €1.01 billion.

Some degree of privatisation appears inevitable but sales will undoubtedly involve the exchequer incurring big costs in order to bring in some much-needed cash. Can this be justified? Perhaps, if there are compensating gains such as improved enterprise performance and public service delivery. However, the Irish track record is not hugely impressive in this regard.

The question of privatising public enterprises requires careful consideration of all the costs and benefits. Ideally the decision to sell these companies should be made in the context of an overall strategy for the sector, but this doesn’t exist. Instead, the issue of privatisation is under consideration as a revenue raising measure. Past experience shows us that there are reasons to be fearful about the quality of decision making in relation to the disposal of such assets. The firesale approach that appears to be imminent is a worrying development.

Moody's downgrades - an investment upgrade required

However, Dietmar Hornung, Moody's lead analyst for Ireland, was a bit more categorical. He said, "Today’s downgrade is primarily driven by the Irish government’s gradual but significant loss of financial strength, as reflected by its deteriorating debt affordability." So, while there are a serious of contributory elements, the downgrade is primarily a function of the weakness of government finances, highlighted by deteriorating debt affordability.

The weakness of taxation revenues reflects the ongoing weakness of the domestic economy- the sector that the government chooses to tax. But the affordability of debt is no less serious. As existing debt government debt matures it has to be replaced by new debt issuance, and, now at higher interest rates. At the same time, borrowing is required to meet the tax-induced widening of the deficit. On top of this, the government, who can in no way risk the country's international reputation by borrowing a cent for investment purposes, can repeatedly find the resources to provide further bank bailouts.

All of this is leading towards disastrous outcomes. This is reflected in the market interest rates on government debt, and does not support the idea widely promoted that the economy is being rewarded for its fiscal austerity drive.

The market interest rate on Irish 10yr government debt is now 5.5%. By comparison the market interest rate on German 10yr government debt is 2.59% and Spain's 10yr debt yields 4.62%.

So, a €10bn 10yr bond issued by NTMA would cost, more or less, €15.5bn in interest and debt repayments over the life of the bond, whereas it would cost the German Treasury €12.6bn, Spain €14.6bn. There are auctions of Irish government debt scheduled for tomorrow, where we will see how great these 'rewards' are.

Worse, the combination of extremely high deficits and economic contraction is pushing the debt burden ever higher. ESRI is forecasting that general government debt will increase by 20% of GDP this year and 8% next. In the impossible event that no new deficits were incurred thereafter, the domestic (taxed) part of the economy would have to grow at 5.5% in nominal terms simply to keep pace with interest costs. The ESRI forecasts for GNP are for a cumulative fall in nominal GNP of 0.5% over the next two years.

If any business were obliged to borrow at above its competitors' rates, it would ensure that there was a significant positive return on that borrowing. That would be the only way to ensure solvency. Luckily, there is a slew of productive investments that can be undertaken that yield an economic and fiscal return way above the break-even level of 5.5%. They are set out in the NDP. In the Mid-Term Evaluation of the National Development Plan (Fitzgerald & Morgenroth) it places the average annual return on investment at between 14% and 18%, depending on the composition of the investment. If the obligation is to borrow at 5.5%, it makes sense to invest only where there is a much higher return. Investment in the areas, sectors and projects identified by the NDP would close the deficit.

Property Tax (Capital v Income)

But any new property tax must be designed to be progressive. A progressive tax is one where those who can afford to pay more, do so. In that way, money is redistributed from those with more to those with less. In the case of housing, progressivity would require property tax on valuable houses to be multiples of that charged on more modest housing. This will require a system of rates and bands, similar to income tax, and some kind of professional property valuation will be essential.

The Minister is also quoted as saying "One of the problems with capital taxation at present . . . is that we’ve seen this huge reduction in the value of property so that the capacity of the capital taxes to raise money has reduced accordingly," (Irish Times) On one level this doesn't matter. In theory, yes, if property worth €3 million is now worth €2 million, then a 0.1 per cent property tax would bring in less money. But there's nothing to stop the Government raising the amount of tax to 0.15 per cent, in order to restore the amount of money coming in. Should property prices go up, the Government has the option in the annual budget of changing the rates and bands for property tax. On another level, there is certainly a maximum amount of tax that can be taken from capital, which falls as the total value of capital falls. But Ireland is starting from a low base in this regard, so there remains considerable scope to expand taxes on various forms of capital.

The more pressing problem for the tax would be where people are 'asset rich-cash poor'. In other words, someone might have a valuable house but a relatively low income. It is certainly not desirable for the state to be forcing people to sell up and downsize because they cannot pay their property tax. No one is going to tolerate that. Moreover, it would lead to a homogenisation of social classes within different areas; so that only high earners could afford to live in expensive areas, driving out those who inherited property, who retired on a low income pension, etc. Repeated evidence from housing studies shows that tenure mix and social mix is the best way to create vibrant residential areas.

On the positive side, the introduction of property tax could be a long-term stabiliser for tax revenue, which is least damaging to economic growth. In particular, it could stablise local government revenue. That is, it could provide a steady flow of cash coming in every year, without the 'boom and bust' that affected stamp duty and VAT in particular. From that point of view, one solution to the 'asset rich-cash poor' dilemma is for the state to simply take a longer-term view, rather than seek all tax annually. Let people build up a tax bill that will take effect when they eventually sell their property or pass it on as inheritance. Provide a waiver on paying much interest on the tax bill where people genuinely cannot pay, but charge interest in other circumstances to encourage most people to pay annually. But don't pursue arrears aggressively.

This would also solve the dilemma of what to do if a significant number of people refuse to pay. Once a legally robust mechanism is put in place for the state to intercede in any sale or inheritance of property, people will see that non-payment is just putting off the inevitable.

Of course, the value of tax owed will decrease annually, which is why those entitled to a waiver should be charged a small amount of interest, depending on inflation, whereas a mildly punative level of interest could be levied on those not entitled to a waiver.

Such a longer-term approach to collection would also allow the tax to extend to pensioners and others living in valuable housing, without burdening their income. A maximum effective rate of taxation could also be put in place for people entitled to a waiver so that the entire value of a house is not taken in tax. For example, this would facilitate older people 'downsizing' and purchasing a small home.

One major concern, from an equality perspective, is that the debate about 'property tax' is still narrowly focused as a tax on people's homes rather than a discussion about whether we comprehensively tax all forms of property (this argument is expanded here). This disproportionately puts the emphasis on people on middle incomes, rather than wealthier people who may have financial assets and other forms of property. Where other property is already taxed, we should look at making the effective level of tax paid more uniform across different forms of capital, and also seek the principle of progressivity to be extended so that those with larger amounts of assets pay increasingly higher rates of tax.

If a tax system as a whole (inclusive of tax breaks, etc) does not adequately redistribute wealth, then a relatively small number of people and companies in every generation will acquire more and more assets. This is not sustainable. If established in a progressive way, property tax could be a useful way of ensuring that a steady redistribution of wealth occurs in every generation.

Sunday 18 July 2010

China (II) - Investment in China

In the first post I examined the huge growth of Chinese investment in the rest of the world. In this post I will briefly look at the other side of the investment coin – foreign direct investment in China and unionisation in MNC plants and offices. The growth in FDI into China quickly grew to over $108bn in 2008, the last figures from UNCTAD. This is equivalent to 6% of total investment in China. Outward investment from China was $52bn in 2008 and is undoubtedly higher today.

Western firms have been pouring investment into China. On 8th July, Peugeot announced a €1bn joint venture with a Chinese car company in new plants in China.

Yet some MNCs are baulking. Google’s decision to exit its Chinese business because of censorship was unusual as it is a major company which was willing to make a strong statement – eventually! However, a compromise was reached recently with the Chinese government in early July and Google will stay. In its licence-renewal application, Google pledged to “abide by Chinese law”. The level of censorship to be imposed and accepted by Google is as yet unknown. Other foreign firms put up with intimidation and often have to indulge in bribery to Communist Party officials.

The recent harsh prison sentences imposed on four Rio Tinto employees in Shanghai for bribe-taking of between seven and 14 years for bribery and theft of commercial secrets (only one of them admitted the second charge) has scared many western firms. The employees were three Chinese and one an Australian of Chinese descent. The American Chamber of Commerce in China found that many American firms feel shut out of Chinese markets because of “discriminatory government policies and inconsistent treatment by the legal system.”

One advantage for western multinationals in this “workers’ state” is the absence of free trade unions. There are only yellow unions in China. They are similar to the yellow unions in Ryanair or Quinn Insurance – not free trade unions but in-house “representatives.” The All-China Federation of Trade Unions, (ACFTU), the country’s union organisation, is closely linked with the Communist Party. Union representatives in companies have to be approved by the union federation. They are thus linked, perhaps indirectly, to the Chinese government. So unionisation can link in the state into management.

Yet Chinese workers in many plants have been ignoring the state controlled unions and confronting management. The ACFTU has been forced to increase its efforts to recruit members after industrial unrest, which stopped the China operations of two Japanese carmakers.

At the Honda plant, worker representative, Ms Li issued an open letter on behalf of the 16 employees chosen by workers to negotiate on their behalf, during the strike which closed Honda’s China operations for a week. “We must maintain a high degree of unity and not let the representatives of Capital divide us,” the letter urged. “This factory’s profits are the fruits of our bitter toil ... This struggle is not just about the interests of our 1,800 workers. We also care about the rights and interests of all Chinese workers.” The strike was quickly followed by two other strikes in two other Honda plants in China. Yet at rallies, most Honda strikers were fearful of the state and hid their faces with surgical masks and few would give their full names to the media.

The result: the workers won a 25% increase in pay to €230 a month! Most commentators do not think even 30% pay rises will lead to noticeable price increases in the West, but are more worried that strikes will disrupt supply chains. If this happens, the authoritarian state may step in.

Most foreign companies do not accept unions to date. But many commentators are saying that if they want to operate in China, they may have no choice from now on. It has been seen that the Apple IPod is made under very stressful conditions for its non-unionised workers, many of whom were so stressed that they have committed suicide. Great, progressive steps to prevent more suicides have been taken by Apple’s supplier. For example: Nets to prevent jumping off factories have been put up, “counseling” and pay rises have been “imposed” by Foxconn, the kind sub-contractor, to reduce stress! It is largely controlled by one staggeringly rich man.

Foxconn is the world’s largest contract electronics manufacturer, whose clients include Apple, Dell and HP. Some assert that it is one of the better employers with a fine campus with a large swimming pool and many other facilities at its “factory town” in Shenzhen, near Hong Kong. Yet it has been shaken by the high-profile series of suicides. And rightly so, for a fine pool is no good when you are treated like a serf in the factory working very long hours, doing repetitive and really tedious work under quasi-military guard. And other employers are even more nervous too. Whether free trade unions will be allowed to operate remains to be seen, but it is unlikely in the short run.

Up till recently, big companies have been welcomed in China for providing foreign capital and skills, and they were not asked by the state to allow the workers to organize (nor have workers been given this right in law), or rather, to be told by government what union to accept. Unions are mild in China but there is now a 2% charge on payroll in the companies where unions do exist. It may be used for workers' health care and other “benefits”. The FT reported that “They are actually telling us [to establish union chapters], not asking us,” said one foreign executive in Suzhou. “The feeling from everyone was – we just got a 2 per cent tax.” “In Europe or America, having a union is like having a [rival] manager in the company,” said a government official. “Here a union is to help the company be more productive.” Well those are two views of the comrades and the MNCs!

This increased worker militancy may impact on consumers as costs will rise at key stages in the thousands of supply chains that bring them electronics, clothes and toys. Workers are more skilled an,d with greater investment in capital and in skills, productivity is rising. The workers’ share was not at all equitable and they are now becoming more militant. Thus wages and then prices will rise. This is not bad as it would help reduce Chinas huge foreign surpluses in time, though for many Chinese products, like electronics, labour costs are but a fraction of total costs. Increased wages and salaries will re-orientate consumption to China’s growing middle class too, shifting more consumption to the domestic market.

Unionization had been mainly been confined to those industrial hubs which have a history of union activity, such as Guangdong and Tianjin, east of Beijing. Wal-Mart rejected unionisation in China and then pulled out, and Microsoft is currently resisting a unionisation drive. The FT recently reported that the “union officials in Beijing’s financial district summoned representatives of multinational investment banks to a meeting last month at which they were encouraged to establish union chapters.” The banks included Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan, Morgan Stanley and UBS.

Thursday 15 July 2010

What goes around the track comes off the track

Oh, and now the IMF. In their recent report they projected, under current fiscal policy, when the deficit would come into Maastricht compliance. What year? 2016 or 2017. This didn’t get much prominence. I read the newspapers this morning and not one mention (if I’m mistaken, please let me know). Still, when this becomes known, I wonder what the response will be. Condemnation of the IMF? Exhortations to cut even more (Dan O’Brien wants us to have a go at pensioners)? An apology to ICTU? Guess which response is the most likely.

The IMF’s projection shouldn’t surprise us. A few weeks ago, Ernst & Young / Oxford Economics examined the issue and, on current strategy, projected the deficit wouldn’t come into Maastricht compliance until 2018 or 2019. Indeed, I have not met any economist – regardless of their ideological complexion – who, hand on heart, believes that 2014 is a realistic goal.

One merely has to compare Government and IMF growth projections up to 2015 to understand why 2014 is merely aspirational. IMF estimates growth to be substantially less than what the Government is predicting; in particular, the IMF suggests that GNP growth, or domestic activity, will be nearly half what the Government expects. With limited growth comes lower tax revenue and higher unemployment expenditure: hence, a consistently larger deficit.

Why would growth be so understated? The ESRI is ready with an answer (from the full commentary, not available yet on-line).

‘The impact on the wider economy (of the Government’s planned €3 billion fiscal adjustment) is to reduce the growth rate by approximately one percentage point. In addition, the level of employment is lower and emigration flows higher than in the absence of such a package. These are real costs attached to the programme of fiscal consolidation being pursued by the government.’

Of course, the ESRI feels we should proceed with the deflationary fiscal adjustment regardless. Why? Because we have to reduce the deficit. But is it reducing the deficit? Not really; it is resulting in sluggishly high deficits and higher overall debt levels. But we have to cut the deficit . . . and so we are trapped in a vicious circular argument.

So if we proceed with deflationary spending cuts to cut the deficit we will reduce growth which will, in turn, create higher than anticipated deficits. How can we escape this deflationary-deficit trap?