Michael Burke: In today's Financial Times, chief economics commentator Martin Wolf has an interesting piece on how we can get out of the crisis. He argues that conventional wisdom about the prospects for economic recovery, and the policy adjustents that will be necessary, is completely wrong.

"The conventional wisdom is that it will also be possible to manage a smooth exit. Nothing seems less likely."

The reason for his more sober assessment is the trend in private sector financial balances; that is, the growing surpluses of private sector incomes over private sector expenditures. For the OECD as a whole this surplus is projected to reach 7.4% of GDP this year. Six countries, Ireland is one of them, will run surpluses of more than 10% of GDP. In Ireland's case it is projected that the private sector will earn more than it spends to the equivalent of over 15% of GDP, the third highest of OECD economies behind only Spain and Iceland.

This has been dubbed 'the paradox of debt' by Paul Krugman, following the Keynesian notion of the 'paradox of thrift'. The argument is that, while for each highly-indebted company or individual it makes sense to save, or, in the current climate pay down debt, for the economy as a whole it is disastrous. The aggregate saving reduces final demand, both household spending and business investment and thereby deepens the recession. Incomes for individual and companies fall further, so they repsond by cutting expenditures further, and so on.

There are many criticisms of this notion from what has become orthodoxy over the past several years. The only serious one is that, if the private sector saves in this way but continues to consume and invest in the same proportions all that will then happen is that prices will fall, and goods and services will be cheaper at the new, lower level of spending. However, this ignores two trends that occur in crises and are happening currently, most especially in Ireland.

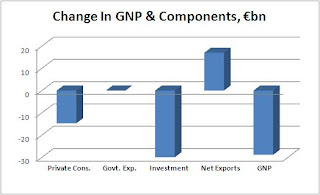

The first is that investment tends to fall much faster than consumption, for obvious reasons. Of a total decline in Ireland's GNP of €28.9bn, personal consumption has fallen by 15.1% (€14.7bn) and investment has fallen by 52.5% (€30bn). In fact, as the data shows, the fall in investment accounts for more than the entire decline in GNP, with the difference mainly accounted by foreign earnings. This pattern, where investment is the main driver of the recession, is replicated across the OECD although in some other countries it is net exports which have also plunged, not private consumption as in Ireland.

The second reason why this orthodox criticism is invalid is the level of debt. As prices fall, as they have in Ireland, the real level of the debt only increases. The many vociferous calls for 'competitive deflation' ignore this fundamental fact. Not only is (un)competitiveness a misdiagnosis of the current situation, but the 'cure', lower prices in Ireland than the rest of the EU would only increase the debt-servicing burden for all who earn their incomes in Ireland, individuals, companies and the government.

To return to the Martin Wolf article, he argues that, while extremely loose monetary policy has been necessary, by itself it stores up two alternative problems, both of which lead ultimately to disaster. One possibility is that cheap money reignites a boom in consumption, which itself just postpones an even bigger future financial crisis. The other possiility is that there is no recovery in consumption and the fiscal poston deteriorates further, to the point of widespread government defaults.

Happily, there is another option. Or actually two, according to Wolf, one of which is a surge in demand in 'emerging' economies. But for highly indebted countries like Ireland the policy option to avert disaster is clear: "a surge in private and public investment in the deficit countries ....[where] .....higher future income would make today’s borrowing sustainable."

He argues that the hope that the world will go back to as it was before the crisis is forlorn one. As we have already seen, it is the huge investment deficit which is driving the recesson, and only an enormous increase in invesment can restore both prior levels of activity and government finances.

"Let us not repeat past errors. Let us not hope that a credit-fuelled consumption binge will save us. Let us invest in the future, instead."

7 comments:

@Michael,

Many thanks for highlighting this excellent piece. Martin Wolf has proved to be the clearest advocate of economic rationality. Unfortunately, this Government and its two predecessors have dug Ireland into a deeper hole than other high-income, deficit countries. Its desire to prevent a total meltdown of the property sector (that would wipe out its main financial supporters) and to retain private, but predominantly Irish, ownership and control of the zombie domestic banks is preventing the pursuit of the required policies to convert significiant private sector savings into the investment required.

And this is from the party with whom, I suspect, many posters on this site believe the Labour Party could form a colaition government in the future.

I think it's time to get real and to remove this lot before they do any more damage.

@ Paul,

I think it's fair to say that most posters on this site would like a Labour-led government, whether that were with FG, FF or some coailition of the left. Of course if wishes were ponies we'd all have ponies...

@ Michael,

I don't have access to this particular article but I think it's fair to say Martin Wolf wouldn't advocate fiscal expansion in Ireland. That being the case, and with private investment collapsing as you show, the only way to increase investment (in the Wolf/orthodox view where fiscal expansion is not viable here) is a big increase in public investment, presumably funded by both tax increases and cuts in government consumption or transfers.

The "increase public investment in face of collapse in private investment" part should be uncontroversial. Some but not all (possibly not even most) orthodox voices would reject the tax increase part. Most people at this site would seem to reject the cutting government consumption/transfers part, mostly because they would reject the rejection of fiscal expansion/stimulus.

I'm not really qualified to say who's right or wrong on this, just pointing out (what is perhaps obvious) that support for increasing public investment is not the same as support for fiscal expansion (and does not imply opposition to fiscal retrenchment).

Hi James

If you click on the 'interesting piece' phrase in the first paragraph, you can read the whole article.

Wolf does advocate increased government investment for all the highly-indebted countries, and Ireland is one of the most highly indebted.

Increasing government investment to plug the gap in private investment is highly controversial in Ireland where it matters; the government and its supporters. In response to the private sector's investment strike, the government has responded by cutting its own spending and investment.

This is entirely incorrect. It has depressed activity, driven up unemployment and reduced taxation. All of these things have increased the deficit, not reduced it, even with swingeing tax cuts.

The alternative is to increase spending, boost activity and taxes and reduce the deficit. I have no idea how much of this spending needs to be financed by increased taxation. Perhaps very little.

Taxation instead could be used to produce a fairer, better and less crisis-prone Ireland.

What is clear is that, if taxes were increased on some activities, like capital gains, other offsetting measures would need to be introduced to ensure that there was no net contraction in demand. Maybe, say, tax credits for anyone enrolling on a training course or credits for single parents' child care, or a return to free medical cards, this time for a much wider section of the population, etc.

Given the higher propensity to consume of the lower paid, these fiscally neutral tax changes would actually boost activity and therefore tax receipts, and lower other costs, leading to lower deficits.

Literally, the government cannot afford to carry on cutting.

If you click on the 'interesting piece' phrase in the first paragraph, you can read the whole article.

I think James may be referring to the fact that most people, as soon as they click on the article, will hit the FT paywall.

The way to get around it is to note the article title and search for the title in Google News and click through from there.

Michael, What I found most most interesting in Wolf's article is the graph which does not appear in downloaded version. It shows the increase in private sector financial balances. Ireland is the third highest of all OECD countries, after Iceland and Spain with a 16% increase between 2007-2010. In short, the private sector is on a spending strike. Wolf argues that states have to compensate. And Ireland's government, composed of anti-Keynesian Cameron Tories, is also on strike!

Private Spending Strike + Public Spending Strike = Deeper Deflation

Apologies all; the article is titled

The world economy has no easy way out of the mire, by Martin Wolf.

@ Anonymous

Exactly, if the government joins the private sector in increasing its savings final and intermediate demand collapse. And since all, including government, are dependent on the other sectors for their incomes, the decline in incomes worsens the debt problem.

As Mr Wolf points out regarding emerging economies much of the decisions regarding the extent of public investment may depend on the world you expect to awaken to after the recession.

An arguement i tried to articulate some months ago here was that the technological development that is coming in the next number of years is certainly considerable. The management of the financial aspects of all of these new technologies and areas of advancement, of course, will dictate whether or not we over stretch and lean towards the betterment of the few to yet another crisis or not, but what one can see with just a cursory glance at the tech, biotech, nanotech, genetic and robotic worlds is that we can certainly afford to invest.

In terms of just how exponential tech growth will be and remain in the future it seems (at the most conservative estimates) safe to liken the immediate future as a group (in their times) wondering if it would be wise to invest in these new rialroads, or combine harvesters or computers?

This, arguement is actually an aside to the deflationary aspect of current policy and whether public investing into a non-developing world would at least act as a counter balance to this negative cycle. I would argue that in light of what is coming we could and should borrow for the medium and long-terms even if it did not have the positive spin-offs that so many have elucidated here and elsewhere.

Post a Comment