Michael Taft: Just because some people don’t get it – that shouldn’t stop us from getting it. Colm ‘Digger’ McCarthy was at it again, calling upon the nation to dig an even deeper hole. We have engaged in deflationary policies in order to please the markets. This obviously isn’t working. What’s the solution? More deflationary policies.

‘ . . . the government needs to re-state as forcefully as possible its commitment to fiscal consolidation, and to ignore the irresponsible cacophony of demands for additional spending. We will be lucky if we can borrow enough to keep the show on the road.’

Along the way, certain facts have to be ignored and unsubstantiated assertions repeated. For instance, the deflationary interventions last year produced benefit to Irish borrowing costs. It didn’t – as shown here. Borrowing costs increased after each ‘budget’ the Government introduced (February pension levy/spending cuts, April emergency budget, 2010 budget).

Then we got the ‘We’re not Spain, Italy or Portugal’. No, we were worse, despite some commentators’ determination not to read the indices. Of course, they had to say this because admitting things were going south would beg questions about the efficacy of deflationary policies.

Now we’re getting a ‘We were doing the right thing, the markets knew we are doing the right thing but the Euro crisis was outside our control and we unfortunately got swept into the maelstrom.’

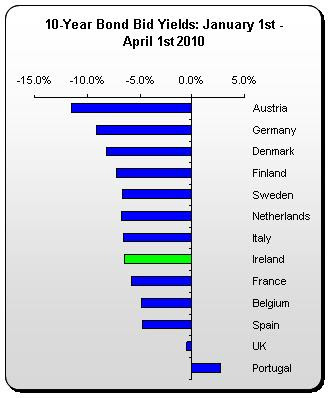

Under this narrative, Irish debt was improving up to April – proof that the markets were satisfied. The problem for this narrative is that all EU-15 countries debt was improving (save for Greece and Portugal); but Ireland was improving less than most other nations. And some of those countries whose debt didn’t improve as much in percentage terms as Ireland’s (e.g. Belgium and France) – well, their borrowing costs were much, much lower than ours to start with.

Still, the spin continues. Only this morning we have this gem from the Irish Independent:

‘ASIDE from bond yields that aren't as high as others in the eurozone, the rewards for Ireland's early frugality have been slow to come.’

What index could they possible be referring to? Excluding Greece (who’s not in the market), Irish 10-Year spreads are the worst in the EU-15. According to the Irish Times Saturday index Irish 10-spread came in at 2.53. Next in line is Portugal at 2.51. Every other country is well below.

False narrative, missed facts, bad prescriptions; at least some commentators are starting to express reservations. Peter Bacon said:

‘It is unclear if Europe can sustain fiscal consolidation in the medium term without a growth strategy running in parallel.’

Alan McQuaid said:

‘The 5% interest rate is going too high. My view is that the markets are not buying into the austerity strategy. Telling everybody to get to 3% in two or three years risks knocking the stuffing out of the economy.’

In addition, the Sunday Tribune reports:

‘Ben May, a European economist at Capital Economics in London, warned it would be tough for Ireland to meet the 3% target by 2014 because economic growth rates would unlikely rise back up to historical levels.’

And in the Sunday Business Post, David McWilliams posed the issue this way in arguing for an immediate close down of Anglo Irish:

‘The reason the markets will support closing down Anglo is that markets have no interest in an Ireland that turns itself into a debt-servicing machine to pay for the mistakes of yesterday . . The financial markets are investors who want growth, who want to invest in the real wealth of Ireland and the real wealth of this country . . No investor minds a government spending €20 billion on education and infrastructure because it means the balance sheet will have an asset opposite the debt. But on our national balance sheet opposite the €20 billion is Anglo, with its treasure chest of worthless land and sites. This simple accounting identity scares people.’

At least, in a few quarters, scepticism over deflationary policies is being raised.

We may not be reaching a consensus on a new macro-economic framework – one which emphasises investment, growth, employment, and tax-driven fiscal consolidation. But more and more are starting to ask the difficult questions.

That’s a start.

1 comment:

The deflation trap is a vicious one.

Ireland is the only Euro Area economy to have experienced outright deflation over 2008-10 (5% according to EU, 5.4% according to the more recent OECD assessment).

This means that Ireland's real yields have been soaring, way above even Greece.

This is not an accounting trick or of interest only to bond market geeks. It matters because government has to pay interest and repay debts out of actual taxes collected. If these suffer deflation, as they have, the interest burden rises and debt repayment becomes more onerous.

The self-congratulation on nominal yields is entirely misplaced. Taking deflation into account, it is a travesty.

Post a Comment