Sinéad Pentony: The publication of the preliminary results from the 2010 Survey of Income and Living Conditions (SILC) is very timely in the run up to the budget as it clearly illustrates the impact of austerity measures on the levels inequality and poverty. The results also confirm the findings from TASC’s Equality Audit of Budget 2011, which clearly shows that low income groups lost proportionately more of their income than higher income groups as result of the budgetary measures for 2011. These measures will exacerbate income inequality and lead to growing numbers being put ‘at risk of poverty’ and forced to live in poverty. Given that next week’s budget looks set to continue the failed austerity policies of previous budgets, we can expect to see these trends continue for the foreseeable future. However, there are alternatives, and the choices that are made next week will clearly illustrate the political priorities of the current government.

The headline SILC results show us that income inequality between 2009 and 2010 increased, with the average income of those in the highest income quintile 5.5 times that of those in the lowest income quintile. The ratio between 2008 and 2009 was 4.3 times. The ‘at risk of poverty’ threshold decreased from €12,064 to €10,831, reflecting declining incomes and cuts in social welfare payments over the last number of budgets, and this was accompanied by a sharp rise (12 per cent) in the number of people who are now classed as being ‘at risk of poverty’ - from 14.1 per cent in 2009 to 15.8 per cent in 2010. The proportion of the population ‘at risk of poverty’ is now back to 2006-2007 levels.

One of the most striking figures is the 30 per cent increase in the deprivation rate, which is defined as being deprived of two or more essential items that are deemed essential for meeting basic living requirements. The deprivation rate increased from 17.1 per cent to 22.5 per cent between 2009 and 2010 and the CSO has highlighted the fact that much of the increase has come from those who are NOT ‘at risk of poverty’. The combination of the deprivation rate and at risk of poverty rate gives us the measure of consistent poverty, and this increased from 5.5 per cent to 6.2 per cent. While this might not sound like a lot, the number of people in consistent poverty has increased by almost 50 per cent since 2008, the onset of the current crisis.

Once again, the SILC 2010 preliminary results show us that the groups identified as being most ‘at risk of poverty’ were children and single adult households with children. Almost one in five children were ‘at risk of poverty’ in 2010, with the rate increasing from 18.6 per cent to 19.5 per cent between 2009 and 2010. The ‘at risk of poverty’ rate for households composed of one adult with children was 20.5 per cent. When we look at the rate of consistent poverty, we see once again that children are the group most likely to experience consistent poverty.

The crucial role of social transfers in providing a large proportion of the population with income supports to meet basic needs is also evident, with the results showing us that over half of the population - 51 per cent - would be deemed to be’ at risk of poverty’ if social transfers were excluded from income. In 2004, this figure stood at 39.8 per cent.

These results show us the devastating effects of the policy responses to the crisis on children in particular and on single adult households with children. The burden of the adjustment has clearly been placed on those groups in society that are least able to absorb reductions in income and loss of access to vital public services. There are also strong economic arguments for protecting the incomes of those already on low incomes, particularly in relation to maintaining and boosting demand in the domestic economy.

The National Anti-Poverty Strategy is in tatters, and that there is a need for a complete shift in policy and how we formulate policies aimed at addressing poverty and inequality. All budget proposals should be equality proofed in advance of the budget, and this can only be achieved by undertaking a full distributional analysis to identify how different groups in society are likely to be affected. Budgetary measures should be audited for their effects on different groups after implementation.

We also need to change our system of taxation and benefits to increase the incomes of the low paid and those on welfare. This will have the dual impact of reducing poverty and inequality and protecting existing jobs in the local economy by maintaining aggregate demand. So we potentially have a win-win situation for the economy, and for the society which it should serve.

Wednesday, 30 November 2011

Tuesday, 29 November 2011

Let's see rationales behind Budget decisions

Tom McDonnell: When Minister Noonan stands up in the Dáil next Tuesday it would be helpful if the tax measures he is introducing were accompanied by a set of documents explaining the rationale for each choice being made.

What will be the impact on growth and employment? What about the impact on the most vulnerable in society? What other measures were considered? Why were they rejected and what were the expected impacts of the rejected measures?

The empirical literature strongly argues that taxing property is the least damaging form of taxation when it comes to economic growth and employment. By comparison taxes on labour are more damaging because they directly interfere with economically productive activity. Taxes on low-income workers are particularly damaging because of these worker's high propensity to consume.

Broadly speaking property taxes are composed of:

• Recurrent taxes on immovable property (residential property taxes/site valuation taxes)

• Recurrent taxes on net wealth

• Estate, inheritance and gift taxes (this is CAT in Ireland)

• Taxes on financial and capital transactions (e.g. Tobin Taxes and CGT)

The literature is consistent in its findings. OECD estimates are here.

A shorter document is here.

Table 1 on page 6 has the main results

Each year the European Commission compares the tax burden for all 27 EU countries. The Commission identifies property, environment and consumption taxes as the least damaging to growth (see Box 1 on pages 38-40 of the document)

As an aside you can compare tax burdens for all EU countries on page 282 of the European Commission document (Table 1) – it shows Ireland had the third lowest tax burden in the whole European Union in 2009 - we are a low tax regime (we rank 25th – only Romania and Latvia are lower).

This IMF paper highlights the causal role of growing inequality in generating both the current and the 1929 crises. The authors suggest moving away from taxing the labour of low-income workers, and instead increasing taxes on economic rents, including land, natural resources and financial sector rents.

Not only are property taxes the least damaging to growth and employment but if properly designed (i.e. not a flat rate charge) they are also some of the least regressive forms of taxation. In general, consumption taxes are by far the most regressive taxes and tend to disproportionately impact on lower income groups. On the other hand property taxes tend to impact on the wealthier cohorts.

The TASC Pre Budget Submission has strongly emphasised property taxes as being the most consistent with economic recovery and consistent with social solidarity.

What will be the impact on growth and employment? What about the impact on the most vulnerable in society? What other measures were considered? Why were they rejected and what were the expected impacts of the rejected measures?

The empirical literature strongly argues that taxing property is the least damaging form of taxation when it comes to economic growth and employment. By comparison taxes on labour are more damaging because they directly interfere with economically productive activity. Taxes on low-income workers are particularly damaging because of these worker's high propensity to consume.

Broadly speaking property taxes are composed of:

• Recurrent taxes on immovable property (residential property taxes/site valuation taxes)

• Recurrent taxes on net wealth

• Estate, inheritance and gift taxes (this is CAT in Ireland)

• Taxes on financial and capital transactions (e.g. Tobin Taxes and CGT)

The literature is consistent in its findings. OECD estimates are here.

A shorter document is here.

Table 1 on page 6 has the main results

Each year the European Commission compares the tax burden for all 27 EU countries. The Commission identifies property, environment and consumption taxes as the least damaging to growth (see Box 1 on pages 38-40 of the document)

As an aside you can compare tax burdens for all EU countries on page 282 of the European Commission document (Table 1) – it shows Ireland had the third lowest tax burden in the whole European Union in 2009 - we are a low tax regime (we rank 25th – only Romania and Latvia are lower).

This IMF paper highlights the causal role of growing inequality in generating both the current and the 1929 crises. The authors suggest moving away from taxing the labour of low-income workers, and instead increasing taxes on economic rents, including land, natural resources and financial sector rents.

Not only are property taxes the least damaging to growth and employment but if properly designed (i.e. not a flat rate charge) they are also some of the least regressive forms of taxation. In general, consumption taxes are by far the most regressive taxes and tend to disproportionately impact on lower income groups. On the other hand property taxes tend to impact on the wealthier cohorts.

The TASC Pre Budget Submission has strongly emphasised property taxes as being the most consistent with economic recovery and consistent with social solidarity.

Monday, 28 November 2011

Budget 2012 - Choices

Tom McDonnell: According to Eurostat, Ireland will have the lowest rate of gross fixed capital formation in the EU next year (see pages 68-69 of the pdf).

Fitch partially justified their downgrading of Portugal to junk status on the basis of Portugal's stygian and austerity related growth prospects. As austerity bites harder throughout Europe, the OECD is now forecasting the Eurozone and UK economies will enter recession again next year. In this context Tony Dolphin, the chief economist of the UK think-tank "the Institute for Public Policy Research" (IPPR), has released a short piece suggesting 10 ways to promote growth in the UK economy.

No one denies the Irish Government is heavily constrained in terms of its fiscal stance. However within those constraints the Government still has the ability to make choices. As Olli Rehn wrote today in the Irish Examiner:

“the programme leaves considerable policy discretion to the Government in terms of how to meet its key objectives. It is the Government, and not the so-called "troika", that is responsible for taking the key decisions that matter to the lives of Irish people.”

Ajai Chopra has expressed similar sentiments in the past.

Those who say we have no choices are not being honest. But has the Government chosen well?

The UK's Office of Budgetary Responsibility OBR has looked at the 'impact multipliers' of changes in different taxes and types of spending on growth.

OBR Estimates of fiscal multipliers - tax decreases/spending increases

- Changes in personal tax allowance and national insurance contributions 0.3

- Change in VAT 0.35

- Welfare measures 0.6

- Current spending 0.6

- Capital spending 1.0

What is crucial for policy is the relative efficacy of the measures. Changes in personal tax/social insurance are the least effective measures at stimulating growth while capital spending measures are the most effective. Of course capital spending has the additional advantage of adding to the economy's productive capacity over the longer term. See this discussion last year in the UK parliament on fiscal multipliers. Thus it was a curious decision by the Irish Government to choose to double the level of cuts to capital expenditure. Presumably this was to avoid the politically more difficult choices of increasing taxes and cutting current spending.

Best international evidence suggests the Irish Government's policy choice was the worst decision they could have made in terms of future economic growth and employment. For example see this IMF Position Paper on fiscal multipliers. The effects of the different policy measures can be seen in the Appendices of the document starting on page 22 of the pdf. The IMF paper shows capital spending to be the most effective measure for increasing growth.

Of course cuts to capital spending are politically easier than other choices. One wonders if political concerns are overriding sound economic policy. A lamentable start by the new Government.

Fitch partially justified their downgrading of Portugal to junk status on the basis of Portugal's stygian and austerity related growth prospects. As austerity bites harder throughout Europe, the OECD is now forecasting the Eurozone and UK economies will enter recession again next year. In this context Tony Dolphin, the chief economist of the UK think-tank "the Institute for Public Policy Research" (IPPR), has released a short piece suggesting 10 ways to promote growth in the UK economy.

No one denies the Irish Government is heavily constrained in terms of its fiscal stance. However within those constraints the Government still has the ability to make choices. As Olli Rehn wrote today in the Irish Examiner:

“the programme leaves considerable policy discretion to the Government in terms of how to meet its key objectives. It is the Government, and not the so-called "troika", that is responsible for taking the key decisions that matter to the lives of Irish people.”

Ajai Chopra has expressed similar sentiments in the past.

Those who say we have no choices are not being honest. But has the Government chosen well?

The UK's Office of Budgetary Responsibility OBR has looked at the 'impact multipliers' of changes in different taxes and types of spending on growth.

OBR Estimates of fiscal multipliers - tax decreases/spending increases

- Changes in personal tax allowance and national insurance contributions 0.3

- Change in VAT 0.35

- Welfare measures 0.6

- Current spending 0.6

- Capital spending 1.0

What is crucial for policy is the relative efficacy of the measures. Changes in personal tax/social insurance are the least effective measures at stimulating growth while capital spending measures are the most effective. Of course capital spending has the additional advantage of adding to the economy's productive capacity over the longer term. See this discussion last year in the UK parliament on fiscal multipliers. Thus it was a curious decision by the Irish Government to choose to double the level of cuts to capital expenditure. Presumably this was to avoid the politically more difficult choices of increasing taxes and cutting current spending.

Best international evidence suggests the Irish Government's policy choice was the worst decision they could have made in terms of future economic growth and employment. For example see this IMF Position Paper on fiscal multipliers. The effects of the different policy measures can be seen in the Appendices of the document starting on page 22 of the pdf. The IMF paper shows capital spending to be the most effective measure for increasing growth.

Of course cuts to capital spending are politically easier than other choices. One wonders if political concerns are overriding sound economic policy. A lamentable start by the new Government.

Ireland not an austerity role model ...

Michael Burke: This is an interesting piece from Martin Knijbbe on Ireland as a poster-boy for 'austerity' measures. In response to an article from Jurgen Stark extolling Ireland's export-led recovery, he examines that actual trends in the trade balances of key EU economies currently as well as the growth of both imports and exports. Stark remains a member of the board of the ECB for the time being and argues that 'internal devaluation', wage cuts are responsible for Irish export-led growth. This piece, which originarly appeared on Real World Economics, challenges each of those assumptions.

Crisis update

Tom McDonnell: FT Alphaville is reporting that Moody's is now talking about multiple defaults and a Eurozone break-up. See here for the Moody's press statement while the Guardian is reporting on the widespread market rumours of an impending IMF bailout of Italy. The success or failure of the Belgian, French, Italian and Spanish bond auctions this week should give us a clearer picture.

Wolfgang Munchau has taken a fevered turn and is talking about the Euro zone in terms of days to avoid collapse here. He does point out that technical solutions still exist. These solutions involve the introduction of Eurobonds, the ECB as ultimate lender for sovereigns, and the creation of a Eurozone treasury with oversight over fiscal policy.

Meanwhile Paul Krugman is having difficulty finding a plausible scenario under which the Euro survives.

Gawyn Davies looks at breakup scenarios here.

The EU Summit on December 9 may be the most important yet. This WSJ article provides clues as to the likely strategy from Germany and France. According to the IT Germany is considering elite 'AAA' bonds to be issued jointly with France, Finland, Netherlands, Luxembourg and Austria. Presumably this is predicated on France making it through the year as a AAA country.

One positive development is the increased pressure the ECB is coming under from national Governments to step up its bond buying.

Wolfgang Munchau has taken a fevered turn and is talking about the Euro zone in terms of days to avoid collapse here. He does point out that technical solutions still exist. These solutions involve the introduction of Eurobonds, the ECB as ultimate lender for sovereigns, and the creation of a Eurozone treasury with oversight over fiscal policy.

Meanwhile Paul Krugman is having difficulty finding a plausible scenario under which the Euro survives.

Gawyn Davies looks at breakup scenarios here.

The EU Summit on December 9 may be the most important yet. This WSJ article provides clues as to the likely strategy from Germany and France. According to the IT Germany is considering elite 'AAA' bonds to be issued jointly with France, Finland, Netherlands, Luxembourg and Austria. Presumably this is predicated on France making it through the year as a AAA country.

One positive development is the increased pressure the ECB is coming under from national Governments to step up its bond buying.

Friday, 25 November 2011

The Euro Crisis: is history repeating itself?

Jim Stewart: It is a “common view ... that the world was headed for a massive payments crisis in which several European countries would default on their debts, setting the stage for a general restructuring of all international commitments”.

So writes Liaquat Ahamed in his book ‘Lords of Finance’ (p. 326) in describing the prelude to a conference in 1929 called to reach a final settlement to the German Reparations issue. The conference succeeded in reaching agreement but on terms which eventually lead to financial chaos in Germany and helped precipitate the great depression of the 1930s. Policies that are now regarded as disastrous, were held widely by key decision makers and dogmatically argued. The analogy with policy making and events in the period preceding the great depression of the 1930s and today are striking.

Personal animosities, then as now, are widespread. In 1929 the Governor of the Federal Bank of New York and in effective control of The US central banking system described his German opposite number as an “.. ..exceedingly vain man. This does not take the form of boastfulness as it does a certain naive self assurance” (Ahamed, p. 281). For recent 2011 examples, see Lord Myner's comments on Michael Barnier, the Commissioner for internal regulation. Media reports often cite German annoyance with French Government policies and proposals, see for example here. At an EU summit in October, President Sarkozy is widely reported as telling The Prime Minister of the UK "You have lost a good opportunity to shut up.". Kauder (a leading member of the CDU) has described UK policy as irresponsible and self interested.

But the main problem is the prevailing consensus (held for example by the President of the ECB, the new Prime Minister of Italy, the Governor of the Irish Central Bank etc) that the solution to current economic problems is austerity plus maintaining the solvency of the banking sector at any cost. For short hand this can be termed the Goldman Sachs consensus. The increasing irrationality of such a policy is becoming obvious even to some former supporters. Some examples:-

(1) Ireland, even though it is dependent on IMF and EU loans, and has suffered a hugh recession and economic collapse, was required to pay bondholders in a failed bank even though these bondholders were not covered by any guarantee;

(2) The ECB intervenes in the sovereign bond market while at the same time stating such support will be limited and undesirable. The net effect is that those who wish to sell government bonds such as banks have been able to do so without any medium term effect on bond yields. In effect, such intervention is another support to the banking system.

(3) Where default is both desirable and certain, as in the case of Greece, policy makers perform numerous contortions to try to ensure such a default does not trigger an ‘event’ resulting in the payout on a Credit Default Swap Contract. A Credit Default Swap is similar to insurance on a bond. If the bond defaults the insurance is paid. Such contracts would appear to be one of the greatest financial frauds perpetrated in recent history. Given that policies to ensure debt write downs are not technically a default, buying a CDS contract on government debt, means that the contract will not pay up in the event of default. In any case, in the highly desirable event of a write down of Government debt generally in indebted countries (where Government debt was greater than 60% of GDP, as in the case of Belgium, Ireland, Italy and Portugal), CDS contracts would also not pay out because the counterparty would become insolvent. This is because it is most unlikely that, following the bailouts due to the subprime crisis of AIG and other financial firms, there could be a second massive transfer of resources from the state to the banking sector.

As in earlier periods of financial crisis, commentators assume rationality by decision makers. However key decision makers should be judged by what they say, as distinct from what we hope they think. Take the case of the recently appointed President of the Bundesbank . In a recent interview with the Financial Times, the Bundesbank President stated that the correct response to Greece is “implement what has been decided”. The problem is what has been decided cannot be implemented. Greece does not have the necessary administrative or technical skills, never mind the political will, to implement IMF/EU proposals. The problems with Italy are seen as a problem of “confidence”. Italy has many problems, both political and economic. These reforms will take many years to implement. The lack of confidence in Italian Government bonds is immediate. The Bundesbank President considers the key competitive strength of Germany results from labour market reform. The key strength of Germany relates to its innovative, high productive economy, with a skilled labour force, extensive infrastructure and success in tax compliance (for example using leaked information on deposits held in Swiss bank accounts by German nationals to ensure tax compliance).

There is widespread support for issuing Eurobonds. There are arguments for and against such a proposal (see for example the recent Green Paper on Stability Bonds (Annex 2). Issuing eurobonds could help in the current crisis if applied only to new bond issues, and if existing bonds were not converted into new bonds. Instead they could be transferred to a debt management agency for all or some of the most heavily indebted countries. These bonds could then be written down in value and held until redemption. This is in contrast to the proposals in the EU Green Paper on Stability Bonds, which does not envisage or discuss writing down the value of existing bonds. In addition, the Green Paper does not refer to or discuss the very different economic policies pursued by central banks in the US, UK and Japan, that is large scale intervention in the bond market referred to as ‘quantitative easing’, and the consequent effect on bond yields.

But comments by key decision makers on such a vital topic have been meaningless. For example, the President of the Bundesbank has dismissed arguments in favour of Eurobonds by stating such a policy would be “like drinking sea water to kill thirst”. These and other comments do not give any confidence that key economic policy makers are intellectually equipped to deal with the current crisis.

There is no modern equivalent to Keynes. As in the 1930s, we may have to wait until current policies have demonstrably failed, and are widely recognised to have failed, before there is a change in policy. The cost and problems created could be enormous.

The forthcoming Budget in Ireland is given much media attention. The forthcoming EU summit on 9th December could take decisions that will influence our economic destiny for the next decade.

So writes Liaquat Ahamed in his book ‘Lords of Finance’ (p. 326) in describing the prelude to a conference in 1929 called to reach a final settlement to the German Reparations issue. The conference succeeded in reaching agreement but on terms which eventually lead to financial chaos in Germany and helped precipitate the great depression of the 1930s. Policies that are now regarded as disastrous, were held widely by key decision makers and dogmatically argued. The analogy with policy making and events in the period preceding the great depression of the 1930s and today are striking.

Personal animosities, then as now, are widespread. In 1929 the Governor of the Federal Bank of New York and in effective control of The US central banking system described his German opposite number as an “.. ..exceedingly vain man. This does not take the form of boastfulness as it does a certain naive self assurance” (Ahamed, p. 281). For recent 2011 examples, see Lord Myner's comments on Michael Barnier, the Commissioner for internal regulation. Media reports often cite German annoyance with French Government policies and proposals, see for example here. At an EU summit in October, President Sarkozy is widely reported as telling The Prime Minister of the UK "You have lost a good opportunity to shut up.". Kauder (a leading member of the CDU) has described UK policy as irresponsible and self interested.

But the main problem is the prevailing consensus (held for example by the President of the ECB, the new Prime Minister of Italy, the Governor of the Irish Central Bank etc) that the solution to current economic problems is austerity plus maintaining the solvency of the banking sector at any cost. For short hand this can be termed the Goldman Sachs consensus. The increasing irrationality of such a policy is becoming obvious even to some former supporters. Some examples:-

(1) Ireland, even though it is dependent on IMF and EU loans, and has suffered a hugh recession and economic collapse, was required to pay bondholders in a failed bank even though these bondholders were not covered by any guarantee;

(2) The ECB intervenes in the sovereign bond market while at the same time stating such support will be limited and undesirable. The net effect is that those who wish to sell government bonds such as banks have been able to do so without any medium term effect on bond yields. In effect, such intervention is another support to the banking system.

(3) Where default is both desirable and certain, as in the case of Greece, policy makers perform numerous contortions to try to ensure such a default does not trigger an ‘event’ resulting in the payout on a Credit Default Swap Contract. A Credit Default Swap is similar to insurance on a bond. If the bond defaults the insurance is paid. Such contracts would appear to be one of the greatest financial frauds perpetrated in recent history. Given that policies to ensure debt write downs are not technically a default, buying a CDS contract on government debt, means that the contract will not pay up in the event of default. In any case, in the highly desirable event of a write down of Government debt generally in indebted countries (where Government debt was greater than 60% of GDP, as in the case of Belgium, Ireland, Italy and Portugal), CDS contracts would also not pay out because the counterparty would become insolvent. This is because it is most unlikely that, following the bailouts due to the subprime crisis of AIG and other financial firms, there could be a second massive transfer of resources from the state to the banking sector.

As in earlier periods of financial crisis, commentators assume rationality by decision makers. However key decision makers should be judged by what they say, as distinct from what we hope they think. Take the case of the recently appointed President of the Bundesbank . In a recent interview with the Financial Times, the Bundesbank President stated that the correct response to Greece is “implement what has been decided”. The problem is what has been decided cannot be implemented. Greece does not have the necessary administrative or technical skills, never mind the political will, to implement IMF/EU proposals. The problems with Italy are seen as a problem of “confidence”. Italy has many problems, both political and economic. These reforms will take many years to implement. The lack of confidence in Italian Government bonds is immediate. The Bundesbank President considers the key competitive strength of Germany results from labour market reform. The key strength of Germany relates to its innovative, high productive economy, with a skilled labour force, extensive infrastructure and success in tax compliance (for example using leaked information on deposits held in Swiss bank accounts by German nationals to ensure tax compliance).

There is widespread support for issuing Eurobonds. There are arguments for and against such a proposal (see for example the recent Green Paper on Stability Bonds (Annex 2). Issuing eurobonds could help in the current crisis if applied only to new bond issues, and if existing bonds were not converted into new bonds. Instead they could be transferred to a debt management agency for all or some of the most heavily indebted countries. These bonds could then be written down in value and held until redemption. This is in contrast to the proposals in the EU Green Paper on Stability Bonds, which does not envisage or discuss writing down the value of existing bonds. In addition, the Green Paper does not refer to or discuss the very different economic policies pursued by central banks in the US, UK and Japan, that is large scale intervention in the bond market referred to as ‘quantitative easing’, and the consequent effect on bond yields.

But comments by key decision makers on such a vital topic have been meaningless. For example, the President of the Bundesbank has dismissed arguments in favour of Eurobonds by stating such a policy would be “like drinking sea water to kill thirst”. These and other comments do not give any confidence that key economic policy makers are intellectually equipped to deal with the current crisis.

There is no modern equivalent to Keynes. As in the 1930s, we may have to wait until current policies have demonstrably failed, and are widely recognised to have failed, before there is a change in policy. The cost and problems created could be enormous.

The forthcoming Budget in Ireland is given much media attention. The forthcoming EU summit on 9th December could take decisions that will influence our economic destiny for the next decade.

Who will pay more and who will be protected in Budget 2012

Sinéad Pentony: Budget season is well and truly underway and the slow drip feed of information and kite flying continues. The broad thrust of the fiscal adjustment is presented as a fait acompli – ‘we have no choice’ but to continue on the long hard road of austerity, with those least able to absorb reductions in income and access to essential services being faced with bearing the brunt of the adjustment. TASC and others continue to point out that there is an alternative and this involves ensuring that those who can afford to make a greater contribution to the adjustment are made to do so.

Once again, child benefit appears to be in the firing line and it's filling plenty of column inches. There are also plans for a range of other savings across the Department of Social Protection In the area of health, the proposals being considered include the imposition of an annual fee of €50 for medical card holders along with increases in other user health charges covering prescriptions and access to A&E services.

Even if only some of these proposals make their way into the budget, when they are combined with the confirmation that the main rate of VAT will be increased by two percentage points, this year’s budget is looking very similar to last year’s budget.

In contrast to the debate about where the cuts should be made and by how much, last week Revenue provided details on the amount of tax that was collected through the ‘domicile levy’. This levy of €200,000 was introduced in Budget 2010 on Irish people who are domiciled in Ireland but non-resident for tax purposes. The levy is applied to individuals whose income and assets exceed certain thresholds.

Revenue reported that less than €1.5 million was collected and this was based on a average return of €147,000 by ten individuals who are liable for the levy. The returns are made on a self-assessment basis. Revenue also estimated that, in 2009, there were almost 6,000 individuals who were classed as non-resident for tax purposes and that 440 of these were considered to be very wealthy.

By anyone’s standard,s the domicile levy has failed to ensure that this particular group of Irish people is made to pay their fair share as part of the adjustment. The question is - will the up-coming budget send a clear message that this situation is not going to be tolerated any longer and that other measures are going to be put in place to ensure that the wealthiest Irish people will be made to contribute to the fiscal adjustment on a more equitable basis?

The Community Platform's taxation proposals have highlighted the types of measures used in other countries to tax wealthy non-residents – the US citizen-based tax and the French tax on global assets. The TASC proposals also include measures to increase the level of taxation on assets and passive income from assets held in Ireland, along with reducing the number of days that non-residents can be present in the State from 183 to 90 days.

The economic and equality arguments have been well rehearsed at this stage for targeting taxation measures high earners residing both inside and outside the country. TASC’s Equality Audit of Budget 2011 clearly illustrates who was made to pay more in the last budget. It will come down to the political choices and priorities in relation to who will be made to pay more and who will be protected this time around.

Once again, child benefit appears to be in the firing line and it's filling plenty of column inches. There are also plans for a range of other savings across the Department of Social Protection In the area of health, the proposals being considered include the imposition of an annual fee of €50 for medical card holders along with increases in other user health charges covering prescriptions and access to A&E services.

Even if only some of these proposals make their way into the budget, when they are combined with the confirmation that the main rate of VAT will be increased by two percentage points, this year’s budget is looking very similar to last year’s budget.

In contrast to the debate about where the cuts should be made and by how much, last week Revenue provided details on the amount of tax that was collected through the ‘domicile levy’. This levy of €200,000 was introduced in Budget 2010 on Irish people who are domiciled in Ireland but non-resident for tax purposes. The levy is applied to individuals whose income and assets exceed certain thresholds.

Revenue reported that less than €1.5 million was collected and this was based on a average return of €147,000 by ten individuals who are liable for the levy. The returns are made on a self-assessment basis. Revenue also estimated that, in 2009, there were almost 6,000 individuals who were classed as non-resident for tax purposes and that 440 of these were considered to be very wealthy.

By anyone’s standard,s the domicile levy has failed to ensure that this particular group of Irish people is made to pay their fair share as part of the adjustment. The question is - will the up-coming budget send a clear message that this situation is not going to be tolerated any longer and that other measures are going to be put in place to ensure that the wealthiest Irish people will be made to contribute to the fiscal adjustment on a more equitable basis?

The Community Platform's taxation proposals have highlighted the types of measures used in other countries to tax wealthy non-residents – the US citizen-based tax and the French tax on global assets. The TASC proposals also include measures to increase the level of taxation on assets and passive income from assets held in Ireland, along with reducing the number of days that non-residents can be present in the State from 183 to 90 days.

The economic and equality arguments have been well rehearsed at this stage for targeting taxation measures high earners residing both inside and outside the country. TASC’s Equality Audit of Budget 2011 clearly illustrates who was made to pay more in the last budget. It will come down to the political choices and priorities in relation to who will be made to pay more and who will be protected this time around.

Thursday, 24 November 2011

One more roll of the dice

Tom McDonnell: There seems to be a growing consensus (finally) that only the ECB has the capacity to end the immediate crisis in the Euro zone. The French are now pushing ECB intervention as indeed are the Spanish, Italian and Belgians. Our leaders will get maybe one more roll of the dice to save the Euro. Unfortunately the Merkel doctrine of "no lender of last resort", "no fiscal transfers", and no "countercyclical fiscal mechanism" may yet prevent a happy ending to this story. No number of agreed Treaty changes about interference in national budgets and imposing discipline is going to change that fact.

To prevent meltdown of the currency some form of Treaty change is required to alter the mandate of the ECB. Treaty change to make the ECB a lender of last resort and the introduction of Eurobonds should be expedited. If tighter fiscal oversight is the price then it is worth paying.

Treaty proposals and changes seem inevitable and in that context it is the responsibility of the Irish Government to fully engage with this process to ensure that the proposed new rules and decision making architecture are fit for purpose and consistent with long-term recovery. There is a danger that the events of the last eighteen months have permanently changed the decision making process in Europe in a way that excludes small countries. This is a disturbing development that needs to be reversed.

To prevent meltdown of the currency some form of Treaty change is required to alter the mandate of the ECB. Treaty change to make the ECB a lender of last resort and the introduction of Eurobonds should be expedited. If tighter fiscal oversight is the price then it is worth paying.

Treaty proposals and changes seem inevitable and in that context it is the responsibility of the Irish Government to fully engage with this process to ensure that the proposed new rules and decision making architecture are fit for purpose and consistent with long-term recovery. There is a danger that the events of the last eighteen months have permanently changed the decision making process in Europe in a way that excludes small countries. This is a disturbing development that needs to be reversed.

Monday, 21 November 2011

Let's Have More Budget Transparency

Nat O'Connor: Seán Whelan on RTÉ Six One News last Friday quipped that democratically elected representatives were the first to see Michael Noonan's budget proposals... except that they were not our elected representatives, but those of the German people.

It is unfortunate that the Dáil did not receive the draft papers before the Bundestag, but a more important lesson from the episode is that there is every reason to increase the transparency of budget documentation and proposals from now on.

Irish democracy did not collapse because draft proposals on VAT increases and other measures were circulated before the Government met to consider them. Instead, the democratic process was strengthened by their release.

Strong democracy is when everyone has the right to participate in the decisions affecting themselves and, crucially, the resources they need to do so. Information is just one of the essential resources people need to understand and meaningfully participate; through discussion, lobbying, etc.

Consider the traditional budget process, by way of contrast:

1. All proposals are initially developed in secret by the Department of Finance. (Drafts may or may not be circulated, but certainly not to Opposition spokespersons or the public).

2. Government Ministers are briefed by the Minister for Finance in a meeting of the Government, and may even be asked to agree proposals at the same meeting - without access to alternative expert opinion, advice, etc. Even if they do not agree them in the same meeting, they have only days to seek advice and cannot avail of a richer public discussion with analysis from all perspectives.

3. Some, all or none of the budget proposals may be discussed by Government Ministers with their colleagues on the backbenches of the Dáil. Advice from chosen experts may or may not be sought, at the discretion of each Minister.

4. The final Budget is kept secret until read out by the Minister for Finance on Budget Day. In fairness, the IMF/EU obligation to publish a four-year plan has created more openness.

5. Opposition spokespersons and economic commentators prepare most of their responses in the absence of information about the Budget proposals, often based on rumours or leaks. They are only given minutes to prepare a response to the actual proposals, and must make off-the-cuff responses without research or advice. This makes for shallow analysis that tends to highlight more immediate proposals, or more populist concerns, while neglecting deeper effects on the economy and society.

6. The Dáil votes on the Budget without most of the TDs having read the documents. Strictly speaking, TDs vote on a series of 'financial resolutions' based on the Budget speech. There will be (limited) time for discussion later when the annual Finance Bill, Social Welfare Bill, etc are introduced to make most the resolutions into law. However, votes on resolutions are sufficient for measures that come into effect at midnight. And legislation is sometimes rushed through the Dáil; like last year's Social Welfare Bill the very next day.

Traditional Budget secrecy is seriously flawed and undemocratic. It is also a hugely inefficient and impractical way to run the Government in an advanced economy!

For example, the proposal to raise VAT by 2 percentage points has a range of complex effects on the economy. It requires TDs to know what goods and services attract the standard rate of VAT, as well as to know that VAT dampens employment in the economy less than income tax but more than wealth taxes. The regressive nature of VAT also needs to be explained - that is, that people on lower incomes pay proportionately more of their incomes. It takes time to put together analysis and briefings for those making the decisions, let along for those whose lives will be affected by them.

This year by accident (and again because of the IMF/EU loan) we have a new and improved process:

1. Draft proposals from the Department of Finance are aired in public.

2. Economic analysts (including think-tanks), sectoral lobbyists and the general public are given time to reflect on these proposals and respond to them. An informed public debate is possible.

3. The members of the Government and TDs on both sides of the Dáil can learn from the public discussion and expert analysis. The Government has the option of fine-tuning or even changing proposals.

4. The Budget Day proposals are likely to be less of a surprise and Opposition spokespersons will have had access to information and advice to prepare more detailed and considered responses.

5. TDs have had the benefit of public discussion and contact from their constituents before voting on the Budget.

Does anyone have a problem with making this more open approach permanent?

There are a couple of issues raised by more openness, but in balance I don't think they outweigh the benefits.

The Government is not weakened in its ability to choose to accept or modify proposals. Getting more feedback from lobbies, experts and constituents can only be a good thing. The Government is not exhibiting weakness by changing proposals in the face of evidence, although they would have to justify decisions that appear to simply cave in to politically powerful lobby groups.

(In practice, capitulation to lobbyists tends to happen between Budget Day and the final Finance Act three months later, which often contains quite different proposals - especially on the minutae of tax law - than were in the Budget. However, media and public scrutiny of the Finance Act is very limited).

One tricky issue relates to the 'midnight' proposals: changes that will apply with near immediate effect. For example, excise might change at midnight to prevent people stocking up on alcohol beforehand.

Whether people should get more than a couple of hours warning on such changes is an open question. It may be more effective for raising revenue, but it is arguably more democratic if people know what's being proposed and have a chance to react to it (even if that reaction is a trip to the off-licence). After all, the Government can never fully predict the 'behavioural' effects of Budget changes. And the short-term loss of excise revenue may be off-set by longer-term public understanding and acceptance of how we pay for the services provided by our state.

And if there really are some new taxes that require secrecy before being announced 'with immediate effect', good quality analysis on the day can be preserved through 'lock ins'. They do this in Canada. Several hours before the budget announcements, a selection of Opposition spokespersons and their advisors are locked into a room without mobile phones but with a copy of the budget documents. In another room, a selection of journalists and economic analysts are likewise locked in with the budget. The result is that Opposition responses and expert analysis can be based on the detail of what's being proposed.

Voting on how public money is spent is one of the main purposes of parliament and the Constitution of Ireland makes it very clear that the Government can only spend money in line with budgets agreed by the Dáil.

There is every reason why the vital scrutiny of public money should be as open as possible.

It is unfortunate that the Dáil did not receive the draft papers before the Bundestag, but a more important lesson from the episode is that there is every reason to increase the transparency of budget documentation and proposals from now on.

Irish democracy did not collapse because draft proposals on VAT increases and other measures were circulated before the Government met to consider them. Instead, the democratic process was strengthened by their release.

Strong democracy is when everyone has the right to participate in the decisions affecting themselves and, crucially, the resources they need to do so. Information is just one of the essential resources people need to understand and meaningfully participate; through discussion, lobbying, etc.

Consider the traditional budget process, by way of contrast:

1. All proposals are initially developed in secret by the Department of Finance. (Drafts may or may not be circulated, but certainly not to Opposition spokespersons or the public).

2. Government Ministers are briefed by the Minister for Finance in a meeting of the Government, and may even be asked to agree proposals at the same meeting - without access to alternative expert opinion, advice, etc. Even if they do not agree them in the same meeting, they have only days to seek advice and cannot avail of a richer public discussion with analysis from all perspectives.

3. Some, all or none of the budget proposals may be discussed by Government Ministers with their colleagues on the backbenches of the Dáil. Advice from chosen experts may or may not be sought, at the discretion of each Minister.

4. The final Budget is kept secret until read out by the Minister for Finance on Budget Day. In fairness, the IMF/EU obligation to publish a four-year plan has created more openness.

5. Opposition spokespersons and economic commentators prepare most of their responses in the absence of information about the Budget proposals, often based on rumours or leaks. They are only given minutes to prepare a response to the actual proposals, and must make off-the-cuff responses without research or advice. This makes for shallow analysis that tends to highlight more immediate proposals, or more populist concerns, while neglecting deeper effects on the economy and society.

6. The Dáil votes on the Budget without most of the TDs having read the documents. Strictly speaking, TDs vote on a series of 'financial resolutions' based on the Budget speech. There will be (limited) time for discussion later when the annual Finance Bill, Social Welfare Bill, etc are introduced to make most the resolutions into law. However, votes on resolutions are sufficient for measures that come into effect at midnight. And legislation is sometimes rushed through the Dáil; like last year's Social Welfare Bill the very next day.

Traditional Budget secrecy is seriously flawed and undemocratic. It is also a hugely inefficient and impractical way to run the Government in an advanced economy!

For example, the proposal to raise VAT by 2 percentage points has a range of complex effects on the economy. It requires TDs to know what goods and services attract the standard rate of VAT, as well as to know that VAT dampens employment in the economy less than income tax but more than wealth taxes. The regressive nature of VAT also needs to be explained - that is, that people on lower incomes pay proportionately more of their incomes. It takes time to put together analysis and briefings for those making the decisions, let along for those whose lives will be affected by them.

This year by accident (and again because of the IMF/EU loan) we have a new and improved process:

1. Draft proposals from the Department of Finance are aired in public.

2. Economic analysts (including think-tanks), sectoral lobbyists and the general public are given time to reflect on these proposals and respond to them. An informed public debate is possible.

3. The members of the Government and TDs on both sides of the Dáil can learn from the public discussion and expert analysis. The Government has the option of fine-tuning or even changing proposals.

4. The Budget Day proposals are likely to be less of a surprise and Opposition spokespersons will have had access to information and advice to prepare more detailed and considered responses.

5. TDs have had the benefit of public discussion and contact from their constituents before voting on the Budget.

Does anyone have a problem with making this more open approach permanent?

There are a couple of issues raised by more openness, but in balance I don't think they outweigh the benefits.

The Government is not weakened in its ability to choose to accept or modify proposals. Getting more feedback from lobbies, experts and constituents can only be a good thing. The Government is not exhibiting weakness by changing proposals in the face of evidence, although they would have to justify decisions that appear to simply cave in to politically powerful lobby groups.

(In practice, capitulation to lobbyists tends to happen between Budget Day and the final Finance Act three months later, which often contains quite different proposals - especially on the minutae of tax law - than were in the Budget. However, media and public scrutiny of the Finance Act is very limited).

One tricky issue relates to the 'midnight' proposals: changes that will apply with near immediate effect. For example, excise might change at midnight to prevent people stocking up on alcohol beforehand.

Whether people should get more than a couple of hours warning on such changes is an open question. It may be more effective for raising revenue, but it is arguably more democratic if people know what's being proposed and have a chance to react to it (even if that reaction is a trip to the off-licence). After all, the Government can never fully predict the 'behavioural' effects of Budget changes. And the short-term loss of excise revenue may be off-set by longer-term public understanding and acceptance of how we pay for the services provided by our state.

And if there really are some new taxes that require secrecy before being announced 'with immediate effect', good quality analysis on the day can be preserved through 'lock ins'. They do this in Canada. Several hours before the budget announcements, a selection of Opposition spokespersons and their advisors are locked into a room without mobile phones but with a copy of the budget documents. In another room, a selection of journalists and economic analysts are likewise locked in with the budget. The result is that Opposition responses and expert analysis can be based on the detail of what's being proposed.

Voting on how public money is spent is one of the main purposes of parliament and the Constitution of Ireland makes it very clear that the Government can only spend money in line with budgets agreed by the Dáil.

There is every reason why the vital scrutiny of public money should be as open as possible.

Bad plan, false arguments

Michael Taft: The Minister for Finance’s comments justifying VAT increases are deeply worrying, for they evince either considerable unfamiliarity with basic economic facts; or considerable indifference to such facts in pursuit of a particular agenda. Here’s what he had to say on RTE (22 minutes in):

‘It (the VAT increase) will apply to everybody who purchases things but obviously rich people have a lot more disposable income than poor people and rich people will buy a lot more and will pay a lot more VAT. There’s no VAT of any sort on food and poor people spend a very large proportion of their budget on food so it will not impact as much on the poor as on the well-off people.’

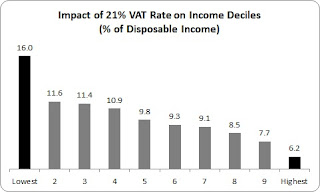

This is wrong. Full stop. It is well known that consumption taxes impact on lower income groups more as they consume most of their income. Indeed, the Minister (or his advisors) would be well aware of a recent study published in the Economic and Social Review in the summer, ‘The Distributional Effects of Value Added Tax in Ireland’ by ESRI researchers Eimear Leahy, Sean Lyons and Richard Tol. They studied the impact of VAT and VAT rises on income deciles – from the lowest 10 percent income to the top (this is a tabular estimate of Figure 10 in the report).

Unsurprisingly, the 21 percent VAT rate has a higher impact on the disposable income of the lowest income groups (16 percent), compared to the highest income groups (6.2 percent). Again, unsurprisingly, average income groups also face a higher burden than high income groups.

This is consistent with the findings from the study by the Combat Poverty Agency/ESRI, which showed that ten years ago total VAT and excise taxes made up more than 20 percent of the gross income of the lowest decile, compared to less than 10 percent of the highest income groups.

So the 21 percent VAT rate hits the lowest income households by more than two-and-a-half times the highest income groups. So much for the Minister’s claim.

But the ESRI researchers also measured the impact of increasing the VAT rate to 23 percent – as the Minister is proposing (again, a tabular estimate of Figure 10 in the report).

Increasing VAT will impact harder on lower income groups – by 1 percent compared to less than 0.4 percent for higher income groups. Again, so much for the Minister’s groundless claim that increasing VAT ‘will not impact as much on the poor as on the well-off people.’

Budget 2011 was bad enough. The low-paid were disproportionately hit through the introduction of the Universal Charge and the reduction of personal tax credits (which amounted to a flat-rate increase in income tax).

But the Minister’s planned VAT rate is even worse for it will not just hit people at work. It will hit everyone, including those on social protection payments (pensioners, widows/ers, unemployed, lone parents, etc.). And the lowest decile group is made up of people living in some of the worst forms of absolute deprivation.

All this has to be set in the wider context. This year, social protection recipients of working age (that is, excluding pensioners) saw their real payments – after inflation – fall by -5.2 percent. Whatever about the leaks regarding Budget 2012, we can reasonably assume that social protection payments will not increase. With the Government’s projected inflation rate, real payments will fall by -1.2 percent. That’s just a start.

Now add in the VAT increases and real incomes will fall further. And that’ s before the myriad of cuts and freezes are applied to child payments, rent and mortgage supplements, etc. It’s looking like another grim year for the poorest in society.

If I were Minister and wanted to protect the living standards of the highest income groups in the state, I would be doing exactly what Michael Noonan is doing – increasing VAT and introducing flat-rate taxes on households. That’s the ticket.

‘It (the VAT increase) will apply to everybody who purchases things but obviously rich people have a lot more disposable income than poor people and rich people will buy a lot more and will pay a lot more VAT. There’s no VAT of any sort on food and poor people spend a very large proportion of their budget on food so it will not impact as much on the poor as on the well-off people.’

This is wrong. Full stop. It is well known that consumption taxes impact on lower income groups more as they consume most of their income. Indeed, the Minister (or his advisors) would be well aware of a recent study published in the Economic and Social Review in the summer, ‘The Distributional Effects of Value Added Tax in Ireland’ by ESRI researchers Eimear Leahy, Sean Lyons and Richard Tol. They studied the impact of VAT and VAT rises on income deciles – from the lowest 10 percent income to the top (this is a tabular estimate of Figure 10 in the report).

Unsurprisingly, the 21 percent VAT rate has a higher impact on the disposable income of the lowest income groups (16 percent), compared to the highest income groups (6.2 percent). Again, unsurprisingly, average income groups also face a higher burden than high income groups.

This is consistent with the findings from the study by the Combat Poverty Agency/ESRI, which showed that ten years ago total VAT and excise taxes made up more than 20 percent of the gross income of the lowest decile, compared to less than 10 percent of the highest income groups.

So the 21 percent VAT rate hits the lowest income households by more than two-and-a-half times the highest income groups. So much for the Minister’s claim.

But the ESRI researchers also measured the impact of increasing the VAT rate to 23 percent – as the Minister is proposing (again, a tabular estimate of Figure 10 in the report).

Increasing VAT will impact harder on lower income groups – by 1 percent compared to less than 0.4 percent for higher income groups. Again, so much for the Minister’s groundless claim that increasing VAT ‘will not impact as much on the poor as on the well-off people.’

Budget 2011 was bad enough. The low-paid were disproportionately hit through the introduction of the Universal Charge and the reduction of personal tax credits (which amounted to a flat-rate increase in income tax).

But the Minister’s planned VAT rate is even worse for it will not just hit people at work. It will hit everyone, including those on social protection payments (pensioners, widows/ers, unemployed, lone parents, etc.). And the lowest decile group is made up of people living in some of the worst forms of absolute deprivation.

All this has to be set in the wider context. This year, social protection recipients of working age (that is, excluding pensioners) saw their real payments – after inflation – fall by -5.2 percent. Whatever about the leaks regarding Budget 2012, we can reasonably assume that social protection payments will not increase. With the Government’s projected inflation rate, real payments will fall by -1.2 percent. That’s just a start.

Now add in the VAT increases and real incomes will fall further. And that’ s before the myriad of cuts and freezes are applied to child payments, rent and mortgage supplements, etc. It’s looking like another grim year for the poorest in society.

If I were Minister and wanted to protect the living standards of the highest income groups in the state, I would be doing exactly what Michael Noonan is doing – increasing VAT and introducing flat-rate taxes on households. That’s the ticket.

Friday, 18 November 2011

Solving the Euro Crisis without Germany Paying More

Nat O'Connor: It seems that domestic politics in Germany are focused on dealing with a perception by German taxpayers that they are at risk of 'paying' for the euro crisis.

Yet, there seem to be obvious political institutional solutions, using the ECB, that could help resolve the immediate euro crisis without the Germans having to 'pick up the bill'.

First of all, and partially an aside, it is calculated by German development bank, Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (cited by the influential Hans Böckler Stiftung, bottom of page 5, in German), that Germany benefitted from having the euro, as a relatively weaker currency than the Deutschmark would have been. They argue Germany benefited by €50-60 billion in the last two years by not having their own currency (which would have been stronger and therefore raised the cost and lowered the competitiveness of their exports). Although this argument is circulating within Germany, it is not influencing the European debate as much as it should.

Secondly, even leaving aside this important line of argument about the less-often-calculated benefits to Germany, there is the obvious solution to any euro crisis: change the rules governing the European Central Bank (ECB). Currently the ECB is constrained to only focus on inflation. It should have a new mandate: to remain strongly independent, but to also focus on maximising employment and also act as a lender of last resort, which John Bruton spoke about very clearly on RTÉ Morning Ireland yesterday (17 Nov).

What the lender of last resort means is that the ECB would buy the government bonds of any state that is having a hard time getting a sustainable rate of interest on the private markets. Of course, if some countries benefit from this facility more than others, that would be effectively a form of fiscal transfer between eurozone members. The ECB would remain independent and could not be instructed when to buy bonds, but it would still be open to excess use.

The risk (to Germany and other stronger economies) is that currently weaker economies (like Italy, Greece or Ireland) might lean heavily on this facility instead of making the necessary (and politically difficult) structural reforms in their own economies and public spending.

One possible solution (and this is open to constructive criticism as I may have missed an equally obvious flaw!) is for a simple mechanism to be instated to resolve this: the ECB could simply keep track of how much each country benefits from it acting as lender of last resort. This record could in turn affect the annual contributions each country has to make to the EU. So although stronger countries like Germany would pay in the short term, this would be equalised in the long term by relatively poorer countries paying a little over the odds in their annual payments to the EU for a period of years (or decades if necessary). Such a mechanism should provide a disincentive for countries to lean too heavily on the lender of last resort and be obliged to make harder domestic decisions. Yet it would prevent the kind of unnessary crisis that Italy and others are facing at this time. (Note that Italy has been running a Government surplus, not a deficit - as I think John Bruton pointed out in the above interview).

The proposal of such an equalisation mechanism might also be the sugar-coating necessary for German voters to accept the need for the ECB to have as full a mandate as the Bank of England or US Federal Reserve.

Yet, there seem to be obvious political institutional solutions, using the ECB, that could help resolve the immediate euro crisis without the Germans having to 'pick up the bill'.

First of all, and partially an aside, it is calculated by German development bank, Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (cited by the influential Hans Böckler Stiftung, bottom of page 5, in German), that Germany benefitted from having the euro, as a relatively weaker currency than the Deutschmark would have been. They argue Germany benefited by €50-60 billion in the last two years by not having their own currency (which would have been stronger and therefore raised the cost and lowered the competitiveness of their exports). Although this argument is circulating within Germany, it is not influencing the European debate as much as it should.

Secondly, even leaving aside this important line of argument about the less-often-calculated benefits to Germany, there is the obvious solution to any euro crisis: change the rules governing the European Central Bank (ECB). Currently the ECB is constrained to only focus on inflation. It should have a new mandate: to remain strongly independent, but to also focus on maximising employment and also act as a lender of last resort, which John Bruton spoke about very clearly on RTÉ Morning Ireland yesterday (17 Nov).

What the lender of last resort means is that the ECB would buy the government bonds of any state that is having a hard time getting a sustainable rate of interest on the private markets. Of course, if some countries benefit from this facility more than others, that would be effectively a form of fiscal transfer between eurozone members. The ECB would remain independent and could not be instructed when to buy bonds, but it would still be open to excess use.

The risk (to Germany and other stronger economies) is that currently weaker economies (like Italy, Greece or Ireland) might lean heavily on this facility instead of making the necessary (and politically difficult) structural reforms in their own economies and public spending.

One possible solution (and this is open to constructive criticism as I may have missed an equally obvious flaw!) is for a simple mechanism to be instated to resolve this: the ECB could simply keep track of how much each country benefits from it acting as lender of last resort. This record could in turn affect the annual contributions each country has to make to the EU. So although stronger countries like Germany would pay in the short term, this would be equalised in the long term by relatively poorer countries paying a little over the odds in their annual payments to the EU for a period of years (or decades if necessary). Such a mechanism should provide a disincentive for countries to lean too heavily on the lender of last resort and be obliged to make harder domestic decisions. Yet it would prevent the kind of unnessary crisis that Italy and others are facing at this time. (Note that Italy has been running a Government surplus, not a deficit - as I think John Bruton pointed out in the above interview).

The proposal of such an equalisation mechanism might also be the sugar-coating necessary for German voters to accept the need for the ECB to have as full a mandate as the Bank of England or US Federal Reserve.

Thursday, 17 November 2011

Embracing "Deadly Sins"

Tom McDonnell: Eurointelligence is reporting that Wolfgang Franz, chairperson of the group of economic counsellors to the German government, is warning that...further ECB purchases of government bonds from the crisis countries would be “a deadly sin".

At a time when rational technocratic responses to the crisis are required, it is disturbing that this is the type of language being used by senior advisers. It may well be a sin to impose tens of billions of private banking debt on a workforce of 1.8 million people. And it may well be a sin to unleash chaos by allowing the Euro to fall because of a dogmatic and intransigent interpretation of the role of the ECB. But changing the mechanisms and protocols of the broken machine that is the currency union is not a sin.

The ECB is now the most important institution in the EU. Its ‘discretion‘ over when and how much it will buy sovereign bonds in the secondary market provides it with the power to topple democratic Governments. Its foolish decisions to increase interest rates earlier this year increased instability, and showed a willingness to put narrow price stability concerns above the wider health of the Euro zone economy and the well being of its citizens. The interest rate increases betrayed a breathtaking failure to understand the seriousness and systemic nature of the debt crisis. The bank has consistently blocked the write down of Irish banking debt. It argues against creating moral hazard and 'dangerous precedents'. Yet it refuses to acknowledge the moral hazard it itself is engendering, by dogmatically insisting reckless lenders escape the consequences of their own actions in contravention of the basic rules of the market. ECB policy effectively reduces the expected ‘cost’ of bad lending and therefore encourages less prudent lending in the future. It is one thing to have an independent central bank. It is quite another to have an incompetent central bank with the power and willingness to threaten and take down Governments it dislikes.

Turning the ECB into a guaranteed lender of last resort for sovereigns would greatly erode its discretionary power and would help end the short-term crisis by ensuring a guaranteed supply of affordable funding for troubled sovereigns. While this could arguably be accomplished through the express wish of the European Council in the short-run (under certain provisions of the Lisbon Treaty), it would almost certainly require treaty change in the medium to long term. Even in the short-run it is clear there is immense hostility to the idea. Jens Weidmann of the Bundesbank gives the German position here, and it is reflective of the view of many core countries. There is little appetite for a changed ECB mandate in the core.

This has existential implications for the Euro because the whole make-up of the Euro zone as it is currently designed is incoherent, fundamentally flawed, and ultimately unsustainable. Even if the ECB was transformed into a normal central bank tomorrow, that in itself would be insufficient to end the crisis. We would still require mechanisms to ensure the survival of systemically important financial institutions, while in the medium term we would need centralised and tighter regulation of the financial sector as well as protocols for winding up insolvent financial institutions.

If the currency union is to work successfully for all member countries in the long term there has to be mechanisms in place for the Europeanization of banking debt, as well as mechanisms for a centralised counter cyclical fiscal mechanism funded from a Euro zone wide tax, for example a Financial Transaction Tax. In a non-optimal currency area such as the Euro zone there must also be a mechanism for compensating less competitive economies for enduring the millstone of a too-strong currency they cannot devalue. This means fiscal transfers. These necessary changes are deeply unpalatable for many in Europe.

The quid pro quo to all these changes would be deeper fiscal integration, more intrusive fiscal oversight for all 17 countries and the creation of a Euro zone finance ministry. Governments could still, as they saw fit, retain the freedom to pursue a low tax/low spend agenda or a high tax/high spend agenda. However they would be required to refrain from running structural deficits. Sustainable fiscal policy should be a goal of Government in any case. Thus as long as a centralised fiscal mechanism is securely in place at the Euro zone level, both to counter-cyclically combat recessions and to provide funding for strategic investment, these fiscal constraints ought not be a major burden for a responsible Government.

Of course deeper integration within the Euro zone will force us to finally address head on the fraught political issue of the trilemma. That issue is beyond the scope of this particular blog post, but for an excellent discussion of the trilemma facing Europe you can read Kevin O'Rourke here and here.

At a time when rational technocratic responses to the crisis are required, it is disturbing that this is the type of language being used by senior advisers. It may well be a sin to impose tens of billions of private banking debt on a workforce of 1.8 million people. And it may well be a sin to unleash chaos by allowing the Euro to fall because of a dogmatic and intransigent interpretation of the role of the ECB. But changing the mechanisms and protocols of the broken machine that is the currency union is not a sin.

The ECB is now the most important institution in the EU. Its ‘discretion‘ over when and how much it will buy sovereign bonds in the secondary market provides it with the power to topple democratic Governments. Its foolish decisions to increase interest rates earlier this year increased instability, and showed a willingness to put narrow price stability concerns above the wider health of the Euro zone economy and the well being of its citizens. The interest rate increases betrayed a breathtaking failure to understand the seriousness and systemic nature of the debt crisis. The bank has consistently blocked the write down of Irish banking debt. It argues against creating moral hazard and 'dangerous precedents'. Yet it refuses to acknowledge the moral hazard it itself is engendering, by dogmatically insisting reckless lenders escape the consequences of their own actions in contravention of the basic rules of the market. ECB policy effectively reduces the expected ‘cost’ of bad lending and therefore encourages less prudent lending in the future. It is one thing to have an independent central bank. It is quite another to have an incompetent central bank with the power and willingness to threaten and take down Governments it dislikes.

Turning the ECB into a guaranteed lender of last resort for sovereigns would greatly erode its discretionary power and would help end the short-term crisis by ensuring a guaranteed supply of affordable funding for troubled sovereigns. While this could arguably be accomplished through the express wish of the European Council in the short-run (under certain provisions of the Lisbon Treaty), it would almost certainly require treaty change in the medium to long term. Even in the short-run it is clear there is immense hostility to the idea. Jens Weidmann of the Bundesbank gives the German position here, and it is reflective of the view of many core countries. There is little appetite for a changed ECB mandate in the core.

This has existential implications for the Euro because the whole make-up of the Euro zone as it is currently designed is incoherent, fundamentally flawed, and ultimately unsustainable. Even if the ECB was transformed into a normal central bank tomorrow, that in itself would be insufficient to end the crisis. We would still require mechanisms to ensure the survival of systemically important financial institutions, while in the medium term we would need centralised and tighter regulation of the financial sector as well as protocols for winding up insolvent financial institutions.

If the currency union is to work successfully for all member countries in the long term there has to be mechanisms in place for the Europeanization of banking debt, as well as mechanisms for a centralised counter cyclical fiscal mechanism funded from a Euro zone wide tax, for example a Financial Transaction Tax. In a non-optimal currency area such as the Euro zone there must also be a mechanism for compensating less competitive economies for enduring the millstone of a too-strong currency they cannot devalue. This means fiscal transfers. These necessary changes are deeply unpalatable for many in Europe.