Sunday, 27 February 2011

The Irish have suffered enough ...

Slí Eile: Interesting piece from today's editorial in the Observer via the Guardian website here.

Friday, 25 February 2011

Problems and Solutions

Sli Eile: Due to Blogger formatting problems, can't post this directly - but click here for a breakdown of the economic issues facing us, counterposing orthodox and unorthodox analyses and responses.

Wednesday, 23 February 2011

From tiger to bailout

Ireland’s deep financial and economic crisis results from failings in its growth model, policy mistakes and systemic failures within European Monetary Union. The bail-out agreement with the IMF and the European authorities and the associated austerity package will not resolve the problems faced by the country and must be renegotiated. Instead a package is needed to promote economic recovery and jobs growth involving elements including: sovereign debt rescheduling and a lower interest rate, fundamental tax reform, and an investment programme financed by the sovereign wealth fund. That's the opening of an ETUI Policy Brief co-authored by former TASC Director Paula Clancy and Policy Analyst Tom McDonnell. The full paper is available for download here.

Tuesday, 22 February 2011

Happy Birthday, Progressive Economy!

Slí Eile: Today, Progressive Economy is two years old. 872 posts later this blog site is learning to walk and talk economics in the market place of ideas. Are you a regular user of this site? What do you think of it? Do you think that it has played a useful role in informing public debate?

Progressive Economy (PE) was set up an alternative forum for debate about ‘progressive economics’. In one way it competes with Irish Economy (IE); in another it complements it. Many people follow Irish Economy and it is cited frequently in blogosphere, the media and elsewhere. While academic economists post for Irish Economy, its readership and commentariat is far and wide and contains not a few critics of the ‘existing order of things’. The focus of IE tends to be a lot on banking and fiscal debt.

Progressive Economy is not defined by what it is not. It seeks to create a different space where the focus of topics and some of the underlying values and assumptions of those post to this site are different. The use of the term ‘progressive’ does not necessarily imply that the views of the mainstream of applied political economy are always regressive. But, sometimes they are because they start from false assumptions, unsubstantiated assertions and a questionable set of values (like we are not short of compassion but cash as if money was a value in itself apart from human labour and society). Many contributors to PE have identified and analysed various data sources that escape mainstream media debates and commentary. One of the services that PE can offer is a commentary on trends, distributions and comparisons in regard to employment, spending, taxation, income, wealth, debt etc Many who continue to post to this Site provide a useful sounding board and criticism of views. This is a vital part of democratic and civil debate to clarify ideas, test assumptions and suggest that there is more than one of conceptualising a problem and certainly more than one way of finding solutions.

So, what conclusions can be drawn from the last two years and what pointers for the next two years? I suggest that:

- The contribution base needs to be expanded while retaining the focus on economics

- More guest posts, ‘head-to-head’ discussions and cross-posting with other sites should be considered.

- Issues around job-creation and industry/services development need greater attention.

At the launch of PE on 23rd February 2009, former Director of TASC Paula Clancy wrote:

Economics has been described as the 'dismal science'. Economists are often stereotyped as conservative, wallowing in bad news, unfeeling and sometimes allied to powerful financial, economic circles and interests…..TASC believes that it is time to reclaim 'economics' by rediscovering the political, social and cultural in 'economics'. We assert that economics is not, and cannot be, neutral. ….A new Political Economy must address the fundamental choices, values and alternative possible ways forward that the traditional practice of 'economics' shies away from. For this reason, TASC has created progressive-economy@tasc to provide a public forum for economic debate.

Progressive Economy (PE) was set up an alternative forum for debate about ‘progressive economics’. In one way it competes with Irish Economy (IE); in another it complements it. Many people follow Irish Economy and it is cited frequently in blogosphere, the media and elsewhere. While academic economists post for Irish Economy, its readership and commentariat is far and wide and contains not a few critics of the ‘existing order of things’. The focus of IE tends to be a lot on banking and fiscal debt.

Progressive Economy is not defined by what it is not. It seeks to create a different space where the focus of topics and some of the underlying values and assumptions of those post to this site are different. The use of the term ‘progressive’ does not necessarily imply that the views of the mainstream of applied political economy are always regressive. But, sometimes they are because they start from false assumptions, unsubstantiated assertions and a questionable set of values (like we are not short of compassion but cash as if money was a value in itself apart from human labour and society). Many contributors to PE have identified and analysed various data sources that escape mainstream media debates and commentary. One of the services that PE can offer is a commentary on trends, distributions and comparisons in regard to employment, spending, taxation, income, wealth, debt etc Many who continue to post to this Site provide a useful sounding board and criticism of views. This is a vital part of democratic and civil debate to clarify ideas, test assumptions and suggest that there is more than one of conceptualising a problem and certainly more than one way of finding solutions.

So, what conclusions can be drawn from the last two years and what pointers for the next two years? I suggest that:

- The contribution base needs to be expanded while retaining the focus on economics

- More guest posts, ‘head-to-head’ discussions and cross-posting with other sites should be considered.

- Issues around job-creation and industry/services development need greater attention.

At the launch of PE on 23rd February 2009, former Director of TASC Paula Clancy wrote:

Economics has been described as the 'dismal science'. Economists are often stereotyped as conservative, wallowing in bad news, unfeeling and sometimes allied to powerful financial, economic circles and interests…..TASC believes that it is time to reclaim 'economics' by rediscovering the political, social and cultural in 'economics'. We assert that economics is not, and cannot be, neutral. ….A new Political Economy must address the fundamental choices, values and alternative possible ways forward that the traditional practice of 'economics' shies away from. For this reason, TASC has created progressive-economy@tasc to provide a public forum for economic debate.

Michael O'Sullivan on need for a 'New Republic'

"As this week’s general election approaches, Irish voters look set to unceremoniously eject the incumbent Fianna Fáil government. But more than a simple change of party, Ireland needs a restructuring of its debt, and profound reckoning with its failed institutions. Only a second Irish Republic can achieve both tasks.

In the bond markets, Ireland’s error has been to take bank liabilities on to its national balance sheet. By then connecting this with entry into Europe’s bail-out fund, the country has set out on a road to serfdom, in which the scale of indebtedness is now likely to smother growth and curb policy flexibility. This week’s election ought to be about how to turn off this road, not how long it should be. Yet Ireland’s national debate still focuses on how to fund debt, rather than how to end insolvency."

You can read Michael O'Sullivan's full opinion piece in today's Financial Times here.

In the bond markets, Ireland’s error has been to take bank liabilities on to its national balance sheet. By then connecting this with entry into Europe’s bail-out fund, the country has set out on a road to serfdom, in which the scale of indebtedness is now likely to smother growth and curb policy flexibility. This week’s election ought to be about how to turn off this road, not how long it should be. Yet Ireland’s national debate still focuses on how to fund debt, rather than how to end insolvency."

You can read Michael O'Sullivan's full opinion piece in today's Financial Times here.

The manifestos and economic policy

Jim Stewart: The publication of the various party manifestos has not been accompanied by detailed scrutiny of many of the policies proposed. There are exceptions (see, for example,the analysis of Parties' proposals for pension reform by Gerard Hughes and Jim Stewart here). One reason for this may be that without expected electoral success, a party manifesto is irrelevant. It may also be because control over the budgetary process and much of economic policy is prescribed by the EU/IMF Memorandum of Economic and Financial Policies which is subject to extensive monitoring (weekly, monthly and quarterly reports). Nevertheless, in some areas there is discretion.

All parties propose renegotiating the terms of the EU/IMF agreement. Electoral change in Germany may make this more likely as the German Governments hard line stance is to some degree determined by electoral strategy (see Quentin Peel, Financial Times, February 21, 2011). As regional elections take place in Germany with defeats for the ruling government, electoral strategy may also lead to a change in economic strategy in relation to EU policies towards peripheral countries, and the role of the European Financial Stability Facility.

The Fine Gael manifesto is of particular interest, as Fine Gael is likely to form the largest party in the next Dail and may even have an outright majority.

Fine Gael Policy Areas/Statements that Require Analysis

The decision to sell state assets (Less Waste, Lower Taxes, Stronger Growth, p. 4) deserves considerable analysis. The assets to be privatised are listed as Bord Gais, ESB Power Generation, ESB Customer Supply Companies, and RTE Transmission Network (Working for Our Future p. 21). Fine Gael criticise (and rightly) the forced fire sale of bank assets (Credit Where Credit is Due, p. 6), yet any sale of Sate owned assets would amount to just that. The economic justification for privatising assets is poorly developed. In addition, the EU/IMF Memorandum of Understanding states “under the period of this financial assistance programme, any additional unplanned revenues must be allocated to debt reduction”. This means selling State assets will be used for debt reduction as in the case of Greece (see Guardian Newspaper 18/11/2019 ‘Greek PM denies plans to sell off national treasures’);

The statement that our effective corporate tax rate is actually higher than that of most EU countries (p. 7) is not supported by the most reliable data available, that is US Bureau of Economic Analysis data;

It is proposed to replace the HSE by new systems by 2016 (Less Waste, Lower Taxes, Stronger Growth, p. 13). In another document it is stated “that the big top down bureaucracies like FAS and the HSE will have been replaced by new systems” (Less Waste Lower taxes Stronger Growth, p. 13). The Manifesto (p. 47) states that the ‘dysfunctional HSE will be dismantled’. Is the fixation with structures really the solution? Are we facing into another five years of chaos while the health system is restructured at the expense of services? It is not clear what institutional structures would replace the HSE, how the new social insurance model will work and how budgets would be allocated.

The Department of Finance is criticised because “it failed to deliver good value for money for taxpayers through public service modernisation and because of the excessive breath of its responsibilities and its culture of centralised control and distrust of the front line” p. 20, See also Reinventing Government, p. 26)).

The Department of Finance can be criticised on many points, but the main failure in economic policy was the destructive policies pursued by McCreevy (decentralisation, deregulation, etc.). Avoiding the pursuit of catastrophic policies in future requires change at many levels, including the near ‘monopoly of the consensus’ in discussions/writing about economic policy, and the consequent silencing of alternative voices.

The formation of an ‘independent’, unelected, fiscal council to which the Minister for Finance will be obliged to either “comply or explain (p. 20) poses many questions. Are we not voting with the intention that those candidates with a majority will have a democratic mandate to form the next Government and be responsible for fiscal policy? Who will be appointed to this independent Council? Many ‘experts’ are not independent of vested interests and especially not independent of an outdated and failed ideology (see blog by Paul Sweeney, A Code of Ethics for Economists). How will such a body avoid being captured by the cosy consensus?

There are welcome proposals, such as the proposed introduction of a loan guarantee scheme. (Working for Our Future p. 265) - but why is it being introduced as a ‘temporary’ measure?

The proposal to use existing banks to administer such this scheme will largely neutralise the scheme and end up subsidising banks as existing loans will be displaced by loans issued under the guarantee scheme.

Note

(1) For example, there is an analysis of Fine Gael and other Parties proposals for pension reform by Gerard Hughes and Jim Stewart at http://www.tcd.ie/business/assets/pdfs/Pensions-Reform_&__Party_Manifestos%5B1%5D.pdf

All parties propose renegotiating the terms of the EU/IMF agreement. Electoral change in Germany may make this more likely as the German Governments hard line stance is to some degree determined by electoral strategy (see Quentin Peel, Financial Times, February 21, 2011). As regional elections take place in Germany with defeats for the ruling government, electoral strategy may also lead to a change in economic strategy in relation to EU policies towards peripheral countries, and the role of the European Financial Stability Facility.

The Fine Gael manifesto is of particular interest, as Fine Gael is likely to form the largest party in the next Dail and may even have an outright majority.

Fine Gael Policy Areas/Statements that Require Analysis

The decision to sell state assets (Less Waste, Lower Taxes, Stronger Growth, p. 4) deserves considerable analysis. The assets to be privatised are listed as Bord Gais, ESB Power Generation, ESB Customer Supply Companies, and RTE Transmission Network (Working for Our Future p. 21). Fine Gael criticise (and rightly) the forced fire sale of bank assets (Credit Where Credit is Due, p. 6), yet any sale of Sate owned assets would amount to just that. The economic justification for privatising assets is poorly developed. In addition, the EU/IMF Memorandum of Understanding states “under the period of this financial assistance programme, any additional unplanned revenues must be allocated to debt reduction”. This means selling State assets will be used for debt reduction as in the case of Greece (see Guardian Newspaper 18/11/2019 ‘Greek PM denies plans to sell off national treasures’);

The statement that our effective corporate tax rate is actually higher than that of most EU countries (p. 7) is not supported by the most reliable data available, that is US Bureau of Economic Analysis data;

It is proposed to replace the HSE by new systems by 2016 (Less Waste, Lower Taxes, Stronger Growth, p. 13). In another document it is stated “that the big top down bureaucracies like FAS and the HSE will have been replaced by new systems” (Less Waste Lower taxes Stronger Growth, p. 13). The Manifesto (p. 47) states that the ‘dysfunctional HSE will be dismantled’. Is the fixation with structures really the solution? Are we facing into another five years of chaos while the health system is restructured at the expense of services? It is not clear what institutional structures would replace the HSE, how the new social insurance model will work and how budgets would be allocated.

The Department of Finance is criticised because “it failed to deliver good value for money for taxpayers through public service modernisation and because of the excessive breath of its responsibilities and its culture of centralised control and distrust of the front line” p. 20, See also Reinventing Government, p. 26)).

The Department of Finance can be criticised on many points, but the main failure in economic policy was the destructive policies pursued by McCreevy (decentralisation, deregulation, etc.). Avoiding the pursuit of catastrophic policies in future requires change at many levels, including the near ‘monopoly of the consensus’ in discussions/writing about economic policy, and the consequent silencing of alternative voices.

The formation of an ‘independent’, unelected, fiscal council to which the Minister for Finance will be obliged to either “comply or explain (p. 20) poses many questions. Are we not voting with the intention that those candidates with a majority will have a democratic mandate to form the next Government and be responsible for fiscal policy? Who will be appointed to this independent Council? Many ‘experts’ are not independent of vested interests and especially not independent of an outdated and failed ideology (see blog by Paul Sweeney, A Code of Ethics for Economists). How will such a body avoid being captured by the cosy consensus?

There are welcome proposals, such as the proposed introduction of a loan guarantee scheme. (Working for Our Future p. 265) - but why is it being introduced as a ‘temporary’ measure?

The proposal to use existing banks to administer such this scheme will largely neutralise the scheme and end up subsidising banks as existing loans will be displaced by loans issued under the guarantee scheme.

Note

(1) For example, there is an analysis of Fine Gael and other Parties proposals for pension reform by Gerard Hughes and Jim Stewart at http://www.tcd.ie/business/assets/pdfs/Pensions-Reform_&__Party_Manifestos%5B1%5D.pdf

Monday, 21 February 2011

Sunday, 20 February 2011

Message for the undecided

Slí Eile: Its not all about economics but economics is a big part of what motivates people to vote or not vote and to vote for that party or candidate and not this. But economics is not a pure science. It is based on values and ideology. Yes, ideology. By this time next week we will know what the coming years will hold by way of Government. It is one part of a long-term process to change our priorities and values.

Election 2011 has been more about the economy than any previous election in living memory. Such strange and novel turns of phrase as burning bondholders, sovereign defaults, Government deficits, deleveraging, firesales, double-dip and 'sharing the pain' etc have become common place in the newspaper, twitter world, radio and some conversations (and people are not entirely switched off as it is claimed over 900,000 people watched some or all of the five-party leaders debate earlier this week).

Ironically, the people most affected by the outcome of this election will be the younger people who will carry the debts and scars of unemployment/emigration for a long time after some politicians have used up their pensions. Yet, the younger under 18 have no voice or say in this election and the sad fact is that in previous recent elections just less than 50% of 18-24 year olds voted and the figure was even lower again among young, male working class voters in urban areas - the very ones most hit by the great moral and economic crisis or our time.

Who would have thought, in 2007, that the nature of politics has changed at least to some extent: a wider choice of parties and candidates on the left, FG and LP arguing furiously over taxation and spending policies, talks of hard bargaining before the outcome of the ballot and the meltdown of that great institution founded in 1926 (but do not assume that death is imminent and do not rule out a recovery...). Who said in 2006 that Ireland was a shining example of the art of the possible in long-term economic policy making' (he is now chancellor of the exchequer across the water)?

What an extraordinary crisis this has been! Financial meltdown, mass unemployment, growing emigration, further and partial loss of national economic sovereignty despair, anger, uncertainty, hope, protest, fear, new expressions of alternative....Will election 2011 bring that much needed transformation of values, vision, policies and delivering of positive outcomes ? - especially for those who have suffered the most (so far) from this crisis (and certainly not those who caused the crisis and suffer much less because of where they lie in the HEAP).

Lets focus on what the 'key issues' are. Never try to answer a badly framed question until you have figured out the right questions first. These, I suggest, are the right questions to start from:

- What is the most effective way to enable people to create and find jobs and income in a way that sustains human life and dignity?

- How do we leave a legacy to the next generations of a cohesive society founded on justice, equality and sustainability?

- How do we as a society manage the distribution of opportunities, capabilities and outcomes relevant to peoples lives?

- How do we provide for a healthy, learning and flourishing society where individuals, families and communities can find their dynamic niche?

Motherhood and apple pie say some commentators, perhaps. Note the absence, so far, in the above list of questions of such terms as fiscal correction, economic growth, competitiveness, debt, borrowing, spending, taxation. Now, all of these latter issues are crucial and without taking a view and course of action on these we cannot properly achieve our individual and social goals. But, the Market, the State, the Economy are not ends in themselves. They are means towards an end - the development of a flourishing society of individuals, families and communities in where well-being comes before one narrow measure of one aspect of well-being, where the needs of the next generations count as much as those of the present, where human rights and needs come before the wants of a few in powerful economic and political positions. In other words people matter and that's the only reason politics, markets and institutions matter.

Election 2011 has been more about the economy than any previous election in living memory. Such strange and novel turns of phrase as burning bondholders, sovereign defaults, Government deficits, deleveraging, firesales, double-dip and 'sharing the pain' etc have become common place in the newspaper, twitter world, radio and some conversations (and people are not entirely switched off as it is claimed over 900,000 people watched some or all of the five-party leaders debate earlier this week).

Ironically, the people most affected by the outcome of this election will be the younger people who will carry the debts and scars of unemployment/emigration for a long time after some politicians have used up their pensions. Yet, the younger under 18 have no voice or say in this election and the sad fact is that in previous recent elections just less than 50% of 18-24 year olds voted and the figure was even lower again among young, male working class voters in urban areas - the very ones most hit by the great moral and economic crisis or our time.

Who would have thought, in 2007, that the nature of politics has changed at least to some extent: a wider choice of parties and candidates on the left, FG and LP arguing furiously over taxation and spending policies, talks of hard bargaining before the outcome of the ballot and the meltdown of that great institution founded in 1926 (but do not assume that death is imminent and do not rule out a recovery...). Who said in 2006 that Ireland was a shining example of the art of the possible in long-term economic policy making' (he is now chancellor of the exchequer across the water)?

What an extraordinary crisis this has been! Financial meltdown, mass unemployment, growing emigration, further and partial loss of national economic sovereignty despair, anger, uncertainty, hope, protest, fear, new expressions of alternative....Will election 2011 bring that much needed transformation of values, vision, policies and delivering of positive outcomes ? - especially for those who have suffered the most (so far) from this crisis (and certainly not those who caused the crisis and suffer much less because of where they lie in the HEAP).

Lets focus on what the 'key issues' are. Never try to answer a badly framed question until you have figured out the right questions first. These, I suggest, are the right questions to start from:

- What is the most effective way to enable people to create and find jobs and income in a way that sustains human life and dignity?

- How do we leave a legacy to the next generations of a cohesive society founded on justice, equality and sustainability?

- How do we as a society manage the distribution of opportunities, capabilities and outcomes relevant to peoples lives?

- How do we provide for a healthy, learning and flourishing society where individuals, families and communities can find their dynamic niche?

Motherhood and apple pie say some commentators, perhaps. Note the absence, so far, in the above list of questions of such terms as fiscal correction, economic growth, competitiveness, debt, borrowing, spending, taxation. Now, all of these latter issues are crucial and without taking a view and course of action on these we cannot properly achieve our individual and social goals. But, the Market, the State, the Economy are not ends in themselves. They are means towards an end - the development of a flourishing society of individuals, families and communities in where well-being comes before one narrow measure of one aspect of well-being, where the needs of the next generations count as much as those of the present, where human rights and needs come before the wants of a few in powerful economic and political positions. In other words people matter and that's the only reason politics, markets and institutions matter.

Wednesday, 16 February 2011

Guest post by Bruce Campbell: Death of the Tiger - a cautionary Irish tale

PE readers may remember that Bruce Campbell, Executive Director of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, spoke last year at the FEPS/TASC Autumn Conference. An edited version of this article, with input from another Autumn Conference speaker, Lawrence Mishel (President of the Washington-based Economic Policy Institute) has just appeared in The Huffington Post.

The Irish people go to the polls on February 25. The governing Fianna Fail party — that created the fallen Celtic Tiger economic model and is now the object of widespread public outrage — will almost certainly be banished to political wilderness, much like the conservative regime casualties of economic crisis in Greece and Iceland.

The Celtic Tiger went from boom to bust with breathtaking speed. In the wake of (in part because of) four austerity budgets—seen as the toughest in Europe-- Ireland is locked in depression with ten successive quarters of economic contraction.

Over the last three years Ireland has seen its national income plummet by over 17%–the deepest and most rapid collapse of any Western country since the Great Depression. Official unemployment climbed 10 points to 14%, and by some measures now exceeds 20%.

Canada’s Finance Minister Jim Flaherty made several trips to Ireland in recent years: pitching Canada-Ireland trade, flaunting his economic management credentials, and it would seem, promoting opportunities in Canada for Irish youth who have been leaving in growing numbers. When I was in Dublin last October, I happened upon a huge banner spanning an imposing building in one of Dublin’s main squares, advertising working holiday opportunities in Canada for Irish students (which I found odd in light of the fact the Canadian youth unemployment rate was hovering around14%.)

On a visit to Dublin in late August 2010, Flaherty—rightly proud of his Irish heritage praised the Irish government on Irish public radio for its draconian public sector budget cuts. “Ireland,” he enthused, “certainly has led the European Union in taking the necessary courageous decisions toward fiscal consolidation”

This was at odds with his government’s own policy of fiscal stimulus. Could it be that Flaherty, the self-professed friend of average working families, was unaware of the catastrophic impact of the savage cuts were having on the Irish population?

Flaherty also praised the Irish government’s decision to guarantee all the debts of its insolvent banks, and criticized the credit rating agencies for not responding positively to what he termed “a solid plan.” What was he thinking? Praising a bank bailout that absolved (mainly foreign) creditors from any liability for their reckless lending; a plan that ballooned the government’s deficit from 12% to 32% of GDP, and public debt to a crushing 130% of GDP.

Until its collapse, the Irish model was widely seen as the poster child of successful development in a globalized era. The darling of conservative policymakers and think tanks, the Heritage Foundation declared Ireland the third most “economically free” country in the world after Hong Kong and Singapore in 2008. George Osborne, now Britain's finance minister, praised Ireland in 2006 as “a shining example of the art of the possible in long-term economic policy making.

It also drew praise from policymakers in Canada, including then Finance Minister Paul Martin. Industry Canada commissioned Québec economist, Pierre Fortin, to do a study of the Irish model and how it could be adapted for Canada. The C.D. Howe Institute praised its positive effects on corporate tax revenue. And of course, its low tax, business friendly, “light touch” regulation aspects greatly appealed to the ideologically conservative Jim Flaherty.

For both men, it provided inspiration for their own corporate tax cut initiatives—Martin lowering the corporate rate (plus surtax) from 28% to 22%, and Flaherty continuing the downward slope from 22% to 15% by next year.

A key pillar of the Irish model was an ultra-low 12.5% corporate tax rate (reduced from more than 40% in the late 1980s) and other tax subsidies to entice high tech multinational corporations to set up bases in Ireland from which to export into the vast European market of which it was now part.

This is not unlike Flaherty’s plan to entice foreign corporations to establish export platforms targeting the US market, a strategy that continues to be hampered by the post-9/11 “thickening” of the Canada-US border. Despite adopting numerous to US security related practices, Canadian efforts to reverse border restrictions have had limited success. The latest of these attempts, the so-called North American Security Perimeter, currently under negotiation, is likely to meet the same fate as earlier efforts, short of a major surrender of Canadian control over, for example, immigration, refugee and information privacy policies.

The Irish model produced a stunning record of economic growth that dramatically reduced unemployment and reversed the historic outflow of Irish labour, and on paper, converted Ireland from Europe’s poor cousin to one of Europe’s richest members.

Foreign direct investment—led by the computer and pharmaceutical sectors--poured in. It became the preferred location of (mainly US) multinational corporations seeking to keep their profits out of reach of their home country tax authorities. (Google, for example, is reported to have saved $3.1 billion over the last three years by setting up shop in Ireland). Ireland became the largest jurisdiction outside the US for declared pretax profits by American firms. The transfer of profits out of Ireland accounts for 20% of Irish GDP.

While indigenous Irish industry expanded, it never lived up to expectations. The hallmark characteristics of an enclave economy--weak linkages to the domestic economy, benefits accruing to a narrow segment of society--were clearly in evidence. Industry remained dominated by a relatively small group of multinationals. Data from the Irish Development Agency, show that while the foreign and domestic sectors each employed about 150,000. The foreign-owned sector accounted for over 80% total output.

While it created a lot of employment—much of it in the form of low wage service jobs—the Irish boom accentuated income and wealth inequality. Rather than apportioning gains to strengthen the welfare state to be more in line with European norms, the Irish model gave precedence to the interests of foreign capital and to a small domestic elite that had successfully ridden the Irish prosperity wave.

The most recent phase of the Irish “miracle” was built on a tsunami-like surge of reckless lending by a loosely regulated banking sector to property developers and homebuyers. They drew on unlimited funds borrowed from willing European and U.S. banks at interest rates cut in half by its membership in the European Monetary Union, and spurred on by government subsidies.

A cozy cabal of politicians, bankers and property developers produced an orgy of speculation, which drove a monstrously unsustainable construction boom and real estate bubble.

At the height of the boom in 2006, construction accounted for 20% of GDP and a fifth of the workforce. Bank lending for construction and real estate rose 1730% from 1999 to 2007. House prices doubled from 2000 to 2006 as household debt soared to 80% of disposable income. Between 2003 in 2008, net foreign borrowing increased from 10% to 60% of GDP. Bank lending standards rivaled the US subprime mortgage fiasco.

Income and capital gains tax cuts left the government coffers with a narrower tax base much more vulnerable to collapse of the construction and real estate sectors.

When the global crisis hit, the bubble burst: foreign finance dried up, exports tanked, construction came to a halt and property values plunged, exposing the toxic debt at the heart of the Irish banks. Ireland’s budget surplus and low public debt turned bad with lightening speed.

It became increasingly clear during the fall of 2010, that the Irish state had sealed its own financial fate by bailing out its banks and now was at the mercy of the European Central bank. In late November, the government basically handed control over to the ECB and International Monetary Fund concluding a massive $110 billion “rescue” package, likened by some to the post-World War I German reparations accord.

The conditions of the loan were punishing: massive public spending cuts and tax increases whose impact would fall disproportionately on low income and vulnerable groups. Ireland’s National Pension Reserve Fund was thrown into the Agreement thereby greatly limiting its ability to make the strategic investments necessary for recovery. It clearly was not a rescue of the Irish taxpayers who were saddled with the entire cost of adjustment.

Those actually rescued by IMF-EU deal were foreign bondholders (mainly European and US banks) who suffered no loss whatsoever. Not a single cent of Irish private bank debt taken over by the government was written down, and the punitive 5.8% interest rates imposed meant that Ireland will be transferring 7% of its national income to foreign bondholders for years to come. Nor did the ECB admit its own culpability or pay any price for failing to rein European banks’ lending spree to the Irish banks.

The Irish think tank TASC reflected the view of many in its assessment of the EU-IMF agreement: “The deal is inequitable, won't work and will either lead to a sovereign default or will condemn the Irish people to a prolonged period of economic stagnation.”

In early December, the government implemented the IMF-EU directive with its fourth and most extreme austerity budget since the crisis began. Three quarters of the spending cuts were to social transfers and public services. They included a 4% cut to social welfare payments and a 12% cut in the minimum wage. The budget’s regressive tax increases fell hardest on middle and low-income workers. Significantly, under pressure from US multinationals and to the dismay of EU countries, the 12.5% corporate income tax rate was spared.

The budget’s cumulative (mainly) spending cuts and tax hikes are equivalent to an astonishing 18% of GDP; or put in a Canadian context, would amount to a $300 billion adjustment. Government officials are predicting this will be offset by rapid export growth. However, with its main markets—Europe and the US—in the doldrums, and no longer able to devalue its currency, this seems like wishful thinking.

The government’s bleeding-the-patient budgetary plan is doomed to failure. It will not produce recovery, create jobs, or restore public finances. And it will increase already high levels of inequality and poverty. As it stands, it condemns the country to years of economic stagnation and untold hardship. A blight on future generations, it accelerates the exodus of youth in search of jobs abroad.

The bank bailout and the ECB-IMF agreement are major issues in the election campaign. The new government will likely push for renegotiation of the Agreement, including a partial debt default or restructuring, perhaps legitimized by a referendum as occurred in Iceland. Failure by the European Central Bank respond to these demands, will raise calls for Ireland to exit the Eurozone, an option seen by many as the “nuclear option:” a cure worse than the disease.

Clearly the Irish model was deeply flawed. Its dynamism was highly dependent on foreign capital and strong export demand. Linkages from the foreign sector to indigenous industry were limited. The rapid accumulation of wealth during the boom years either flowed out of the country or, to the extent that it remained, benefited a small minority. Resources were not used to strengthen public services and distribute income widely. Cuts to personal income and capital gains taxes left the government coffers with a narrower tax base highly dependent property taxes, and hence on continued expansion of the construction and real estate sectors. And in the end, the boom surfed on a construction-real estate bubble in a sea of rotten debt.

All of these features made the Irish model highly vulnerable to collapse as events have shown. At its root was a free market economic orthodoxy that, despite being discredited by the global economic crisis and the failure of many of its star pupils around the world, is unfortunately far from dead.

Long term, the path out of the crisis will involve reconfiguring its development model in a way that more closely resembles the solidaristic Northern European model: greater emphasis on broad based internally generated income and wealth, and its wider distribution in a way that responds to the needs and aspirations of the Irish people.

In Canada, under the Conservative government, disturbing elements of the Irish model are in evidence: a dramatically smaller tax base available for social programs and public services, themselves further crowded out by increased military/security expenditures; a narrower tax base increasingly dependent on commodity (mainly oil) revenues which are vulnerable to major fluctuations in the external environment; a sluggish economy whose main private sector engine over the last two years has been a housing mini-boom that has pushed household debt to unprecedented levels; and historically high and growing levels of income and wealth inequality.

The result of moving down this path is more likely to be a slow motion economic decline than a spectacular flare out as occurred in Ireland. Regardless, continuing to extol the virtues of the now extinct Celtic Tiger will require more than a touch of blarney from our Finance Minister.

Thanks to Sinéad Pentony, head of policy at TASC, for her valuable comments and for making sure I didn’t say anything outrageous. TASC is CCPA’s sister think tank in Ireland.

The Irish people go to the polls on February 25. The governing Fianna Fail party — that created the fallen Celtic Tiger economic model and is now the object of widespread public outrage — will almost certainly be banished to political wilderness, much like the conservative regime casualties of economic crisis in Greece and Iceland.

The Celtic Tiger went from boom to bust with breathtaking speed. In the wake of (in part because of) four austerity budgets—seen as the toughest in Europe-- Ireland is locked in depression with ten successive quarters of economic contraction.

Over the last three years Ireland has seen its national income plummet by over 17%–the deepest and most rapid collapse of any Western country since the Great Depression. Official unemployment climbed 10 points to 14%, and by some measures now exceeds 20%.

Canada’s Finance Minister Jim Flaherty made several trips to Ireland in recent years: pitching Canada-Ireland trade, flaunting his economic management credentials, and it would seem, promoting opportunities in Canada for Irish youth who have been leaving in growing numbers. When I was in Dublin last October, I happened upon a huge banner spanning an imposing building in one of Dublin’s main squares, advertising working holiday opportunities in Canada for Irish students (which I found odd in light of the fact the Canadian youth unemployment rate was hovering around14%.)

On a visit to Dublin in late August 2010, Flaherty—rightly proud of his Irish heritage praised the Irish government on Irish public radio for its draconian public sector budget cuts. “Ireland,” he enthused, “certainly has led the European Union in taking the necessary courageous decisions toward fiscal consolidation”

This was at odds with his government’s own policy of fiscal stimulus. Could it be that Flaherty, the self-professed friend of average working families, was unaware of the catastrophic impact of the savage cuts were having on the Irish population?

Flaherty also praised the Irish government’s decision to guarantee all the debts of its insolvent banks, and criticized the credit rating agencies for not responding positively to what he termed “a solid plan.” What was he thinking? Praising a bank bailout that absolved (mainly foreign) creditors from any liability for their reckless lending; a plan that ballooned the government’s deficit from 12% to 32% of GDP, and public debt to a crushing 130% of GDP.

Until its collapse, the Irish model was widely seen as the poster child of successful development in a globalized era. The darling of conservative policymakers and think tanks, the Heritage Foundation declared Ireland the third most “economically free” country in the world after Hong Kong and Singapore in 2008. George Osborne, now Britain's finance minister, praised Ireland in 2006 as “a shining example of the art of the possible in long-term economic policy making.

It also drew praise from policymakers in Canada, including then Finance Minister Paul Martin. Industry Canada commissioned Québec economist, Pierre Fortin, to do a study of the Irish model and how it could be adapted for Canada. The C.D. Howe Institute praised its positive effects on corporate tax revenue. And of course, its low tax, business friendly, “light touch” regulation aspects greatly appealed to the ideologically conservative Jim Flaherty.

For both men, it provided inspiration for their own corporate tax cut initiatives—Martin lowering the corporate rate (plus surtax) from 28% to 22%, and Flaherty continuing the downward slope from 22% to 15% by next year.

A key pillar of the Irish model was an ultra-low 12.5% corporate tax rate (reduced from more than 40% in the late 1980s) and other tax subsidies to entice high tech multinational corporations to set up bases in Ireland from which to export into the vast European market of which it was now part.

This is not unlike Flaherty’s plan to entice foreign corporations to establish export platforms targeting the US market, a strategy that continues to be hampered by the post-9/11 “thickening” of the Canada-US border. Despite adopting numerous to US security related practices, Canadian efforts to reverse border restrictions have had limited success. The latest of these attempts, the so-called North American Security Perimeter, currently under negotiation, is likely to meet the same fate as earlier efforts, short of a major surrender of Canadian control over, for example, immigration, refugee and information privacy policies.

The Irish model produced a stunning record of economic growth that dramatically reduced unemployment and reversed the historic outflow of Irish labour, and on paper, converted Ireland from Europe’s poor cousin to one of Europe’s richest members.

Foreign direct investment—led by the computer and pharmaceutical sectors--poured in. It became the preferred location of (mainly US) multinational corporations seeking to keep their profits out of reach of their home country tax authorities. (Google, for example, is reported to have saved $3.1 billion over the last three years by setting up shop in Ireland). Ireland became the largest jurisdiction outside the US for declared pretax profits by American firms. The transfer of profits out of Ireland accounts for 20% of Irish GDP.

While indigenous Irish industry expanded, it never lived up to expectations. The hallmark characteristics of an enclave economy--weak linkages to the domestic economy, benefits accruing to a narrow segment of society--were clearly in evidence. Industry remained dominated by a relatively small group of multinationals. Data from the Irish Development Agency, show that while the foreign and domestic sectors each employed about 150,000. The foreign-owned sector accounted for over 80% total output.

While it created a lot of employment—much of it in the form of low wage service jobs—the Irish boom accentuated income and wealth inequality. Rather than apportioning gains to strengthen the welfare state to be more in line with European norms, the Irish model gave precedence to the interests of foreign capital and to a small domestic elite that had successfully ridden the Irish prosperity wave.

The most recent phase of the Irish “miracle” was built on a tsunami-like surge of reckless lending by a loosely regulated banking sector to property developers and homebuyers. They drew on unlimited funds borrowed from willing European and U.S. banks at interest rates cut in half by its membership in the European Monetary Union, and spurred on by government subsidies.

A cozy cabal of politicians, bankers and property developers produced an orgy of speculation, which drove a monstrously unsustainable construction boom and real estate bubble.

At the height of the boom in 2006, construction accounted for 20% of GDP and a fifth of the workforce. Bank lending for construction and real estate rose 1730% from 1999 to 2007. House prices doubled from 2000 to 2006 as household debt soared to 80% of disposable income. Between 2003 in 2008, net foreign borrowing increased from 10% to 60% of GDP. Bank lending standards rivaled the US subprime mortgage fiasco.

Income and capital gains tax cuts left the government coffers with a narrower tax base much more vulnerable to collapse of the construction and real estate sectors.

When the global crisis hit, the bubble burst: foreign finance dried up, exports tanked, construction came to a halt and property values plunged, exposing the toxic debt at the heart of the Irish banks. Ireland’s budget surplus and low public debt turned bad with lightening speed.

It became increasingly clear during the fall of 2010, that the Irish state had sealed its own financial fate by bailing out its banks and now was at the mercy of the European Central bank. In late November, the government basically handed control over to the ECB and International Monetary Fund concluding a massive $110 billion “rescue” package, likened by some to the post-World War I German reparations accord.

The conditions of the loan were punishing: massive public spending cuts and tax increases whose impact would fall disproportionately on low income and vulnerable groups. Ireland’s National Pension Reserve Fund was thrown into the Agreement thereby greatly limiting its ability to make the strategic investments necessary for recovery. It clearly was not a rescue of the Irish taxpayers who were saddled with the entire cost of adjustment.

Those actually rescued by IMF-EU deal were foreign bondholders (mainly European and US banks) who suffered no loss whatsoever. Not a single cent of Irish private bank debt taken over by the government was written down, and the punitive 5.8% interest rates imposed meant that Ireland will be transferring 7% of its national income to foreign bondholders for years to come. Nor did the ECB admit its own culpability or pay any price for failing to rein European banks’ lending spree to the Irish banks.

The Irish think tank TASC reflected the view of many in its assessment of the EU-IMF agreement: “The deal is inequitable, won't work and will either lead to a sovereign default or will condemn the Irish people to a prolonged period of economic stagnation.”

In early December, the government implemented the IMF-EU directive with its fourth and most extreme austerity budget since the crisis began. Three quarters of the spending cuts were to social transfers and public services. They included a 4% cut to social welfare payments and a 12% cut in the minimum wage. The budget’s regressive tax increases fell hardest on middle and low-income workers. Significantly, under pressure from US multinationals and to the dismay of EU countries, the 12.5% corporate income tax rate was spared.

The budget’s cumulative (mainly) spending cuts and tax hikes are equivalent to an astonishing 18% of GDP; or put in a Canadian context, would amount to a $300 billion adjustment. Government officials are predicting this will be offset by rapid export growth. However, with its main markets—Europe and the US—in the doldrums, and no longer able to devalue its currency, this seems like wishful thinking.

The government’s bleeding-the-patient budgetary plan is doomed to failure. It will not produce recovery, create jobs, or restore public finances. And it will increase already high levels of inequality and poverty. As it stands, it condemns the country to years of economic stagnation and untold hardship. A blight on future generations, it accelerates the exodus of youth in search of jobs abroad.

The bank bailout and the ECB-IMF agreement are major issues in the election campaign. The new government will likely push for renegotiation of the Agreement, including a partial debt default or restructuring, perhaps legitimized by a referendum as occurred in Iceland. Failure by the European Central Bank respond to these demands, will raise calls for Ireland to exit the Eurozone, an option seen by many as the “nuclear option:” a cure worse than the disease.

Clearly the Irish model was deeply flawed. Its dynamism was highly dependent on foreign capital and strong export demand. Linkages from the foreign sector to indigenous industry were limited. The rapid accumulation of wealth during the boom years either flowed out of the country or, to the extent that it remained, benefited a small minority. Resources were not used to strengthen public services and distribute income widely. Cuts to personal income and capital gains taxes left the government coffers with a narrower tax base highly dependent property taxes, and hence on continued expansion of the construction and real estate sectors. And in the end, the boom surfed on a construction-real estate bubble in a sea of rotten debt.

All of these features made the Irish model highly vulnerable to collapse as events have shown. At its root was a free market economic orthodoxy that, despite being discredited by the global economic crisis and the failure of many of its star pupils around the world, is unfortunately far from dead.

Long term, the path out of the crisis will involve reconfiguring its development model in a way that more closely resembles the solidaristic Northern European model: greater emphasis on broad based internally generated income and wealth, and its wider distribution in a way that responds to the needs and aspirations of the Irish people.

In Canada, under the Conservative government, disturbing elements of the Irish model are in evidence: a dramatically smaller tax base available for social programs and public services, themselves further crowded out by increased military/security expenditures; a narrower tax base increasingly dependent on commodity (mainly oil) revenues which are vulnerable to major fluctuations in the external environment; a sluggish economy whose main private sector engine over the last two years has been a housing mini-boom that has pushed household debt to unprecedented levels; and historically high and growing levels of income and wealth inequality.

The result of moving down this path is more likely to be a slow motion economic decline than a spectacular flare out as occurred in Ireland. Regardless, continuing to extol the virtues of the now extinct Celtic Tiger will require more than a touch of blarney from our Finance Minister.

Thanks to Sinéad Pentony, head of policy at TASC, for her valuable comments and for making sure I didn’t say anything outrageous. TASC is CCPA’s sister think tank in Ireland.

Economists on Ireland's export performance - more sad stories

Proinnsias Breathnach: One thing that has always struck me about Irish economists is that, despite the importance of foreign direct investment and international trade to Ireland’s economy, they actually know very little about the activities of the transnational firms in question, or the structure of Ireland’s foreign trade and, above all, about the factors which attract foreign firms to Ireland and allow them to use Ireland as a base for serving external markets.

Rather than conducting real research in these areas, most economists who write on these topics appear to draw on undergraduate textbook models of how markets operate – models which in turn were originally devised to explain the kinds of competitive markets for commodity-type products (clothing, food, furniture) which were fairly typical of the British and US economies in the 19th century. Subsequent developments, such as industrial concentration, globalisation, rising living and educational standards, advertising and marketing and technological change, appear to have bypassed many of these people entirely.

Thus, a few weeks ago, we had Anthony Leddin of the University of Limerick (writing in The Irish Times) postulating trends in Ireland’s foreign trade which anyone with knowledge of this area would have realised right away were completely wrong. More recently (January 28), and again writing in The Irish Times, former Central Bank Chief Economist Michael Casey wrote: “At present the only bright spot in the economy is the output and exportation of pharmaceutical products”. This is an extraordinarily uninformed statement for a person of this status to make. Of the nine broad product categories into which the CSO divides Ireland’s merchandise exports, eight experienced growth in nominal export value in the first ten months of 2010 compared with the same period in 2009. Of the total growth in these eight categories, pharmaceutical products accounted for less than half (46.5%).

The growth in total merchandise exports, in turn, accounted for only one half of the overall growth in exports (including services) in the first three quarters of 2010. The growth in exports of computer services in this period exceeded that in pharmaceutical products by 24 per cent. Many economists have been unable to internalise the fact that services exports exist at all, never mind that they have been the main growth sector in Irish exports for many years and, in 2009, accounted for 46.5% of total exports. In the five years to 2009, exports of both computer services and business services grew much more strongly than exports of pharmaceuticals. In 2009, exports of both computer services and business services exceeded exports of pharmaceutical products in value terms.

In that year, these three sectors, along with organic chemicals, accounted for over half of Ireland’s total exports. If we throw in insurance & financial services, food & beverages and office & data processing machinery, the proportion rises to almost three quarters. If one were seeking the key to Ireland’s international competitiveness, one should be looking at why these seven very disparate sectors are able to use Ireland as a successful base for serving external markets.

But this would require some real research. Instead, our economists reach for simplistic and largely irrelevant statistics which are both readily available and tend to confirm deeply-entrenched prejudices. We got a good example of this in an article on Ireland’s competitiveness by The Irish Times’s chief economics journalist, Dan O’Brien, in the issue of February 4 last. While acknowledging that there are many ways of measuring competitiveness and that the National Competitiveness Council employs more than 100 competitiveness indicators in its annual reports,O’Brien then devotes most of the rest of his article to the old diehards – prices and labour costs.

Irish economists have an extraordinary tendency to rely on the EU’s harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP) as a measure of competitiveness, even though its relevance to Ireland’s export competitiveness is not immediately obvious – it is hard to see what bearing the price of a meal or a CD player has on the competitiveness of the organic chemicals or software sectors. Nevertheless, O’Brien regards the fact that Ireland’s HICP fell relative to the rest of the EU between late 2008 and early 2010 as evidence of Ireland “regaining” competitiveness.

O’Brien then suggests that trends in economy-wide unit labour costs (the ratio of wages to net output) are a better indication of Ireland’s improved competitiveness. However, the fact is that the vast majority of the Irish workforce are not engaged in export activity and, again, it is hard to see how the unit labour costs of a waitress or CD player salesperson have a bearing on the competitiveness of the main export sectors identified above. While Ireland’s economy-wide unit labour costs have tended to rise relative to the rest of the EU over the last ten years, the opposite has been the case in unit labour costs in manufacturing, the great bulk of whose output is exported. Yet, while the latter are to be found in the same page in the OECD website as the former, they are rarely, if ever, quoted by Irish economists.

There are no comparable data for export services, but the Forfás Economic Impact surveys indicate that payroll costs as a proportion of value added in foreign-owned export services (which account for 95% of the total) fell from 19% in 2000 to 9% in 2008 – a fall of over 50% in unit labour costs.

This is not to say that labour costs are important (never mind crucial) in the competitiveness of Ireland’s main export sectors. If general labour costs were a key determinant of competitiveness, then one should expect exports in all sectors to be influenced by labour cost trends. However, Ireland’s main export sectors have been very variable in their export performance, and there is no evidence that this variability has been influenced in any way by labour cost trends. Between 2000-2006 (the last year for which the relevant data are available), the chemicals & pharmaceuticals sector experienced volume output growth of 50%, despite a rise of 50% in the share of costs accounted for by pay (up from 12.6% to 18%). In the electronic components sector, there was a more modest rise in the labour share of costs from a lower base (up from 13.1% to 16.4%) yet production volume fell by 7%. In the office machines and computers sector, a fall in labour’s already very low share of total costs (down from 4.1% to 3.5%) produced volume growth of 22% - much more modest than that experienced by chemicals & pharmaceuticals.

The key point is that the idea of Ireland Inc. gaining or losing competitiveness is meaningless. Ireland’s exports are dominated by a small number of sectors whose characteristics are extremely varied and whose export performances are equally varied. Adding up these performances and then concluding from the total that Ireland is becoming more or less competitive is pointless. Over the last ten years Ireland has experienced strong export growth in a range of export services, and in pharmaceuticals and medical devices, modest growth in chemicals, and, overall, a sharp fall in exports of electronics hardware. A wide range of factors account for this export variability, of which labour costs play, at most, a minor role. In compiling its Global Competitiveness Index, the World Economic Forum employes no less than 113 quantitative criteria; in Ireland’s case labour cost factors account for less than two per cent of the total value of the competitiveness index.

The economists’ disconnect from the real world is nicely demonstrated from a passage towards the end of Dan O’Brien’s article. Referring to evidence that average productivity in Ireland has been raised by the collapse of the low-productivity construction sector, he suggested as an example that “a bricklayer produces less than the average assembly-line worker or office drone (sic)”. Productivity in the construction industry is indeed low when compared with manufacturing or business services, but O’Brien’s choice of bricklayers for his example was surely unfortunate. Assuming that earnings bear some relationship to productivity, in 2006, when industrial production workers were earning €601 per week, clerical and secretarial workers €540 and administrative civil servants €819, the average weekly earnings of all skilled construction workers came to €877 and there was one report of bricklayers at that stage earning over €3000 per week! The company making these payments was also reportedly paying its Turkish labourers €2.50 per hour. They might have been a better choice for O’Brien’s example.

Rather than conducting real research in these areas, most economists who write on these topics appear to draw on undergraduate textbook models of how markets operate – models which in turn were originally devised to explain the kinds of competitive markets for commodity-type products (clothing, food, furniture) which were fairly typical of the British and US economies in the 19th century. Subsequent developments, such as industrial concentration, globalisation, rising living and educational standards, advertising and marketing and technological change, appear to have bypassed many of these people entirely.

Thus, a few weeks ago, we had Anthony Leddin of the University of Limerick (writing in The Irish Times) postulating trends in Ireland’s foreign trade which anyone with knowledge of this area would have realised right away were completely wrong. More recently (January 28), and again writing in The Irish Times, former Central Bank Chief Economist Michael Casey wrote: “At present the only bright spot in the economy is the output and exportation of pharmaceutical products”. This is an extraordinarily uninformed statement for a person of this status to make. Of the nine broad product categories into which the CSO divides Ireland’s merchandise exports, eight experienced growth in nominal export value in the first ten months of 2010 compared with the same period in 2009. Of the total growth in these eight categories, pharmaceutical products accounted for less than half (46.5%).

The growth in total merchandise exports, in turn, accounted for only one half of the overall growth in exports (including services) in the first three quarters of 2010. The growth in exports of computer services in this period exceeded that in pharmaceutical products by 24 per cent. Many economists have been unable to internalise the fact that services exports exist at all, never mind that they have been the main growth sector in Irish exports for many years and, in 2009, accounted for 46.5% of total exports. In the five years to 2009, exports of both computer services and business services grew much more strongly than exports of pharmaceuticals. In 2009, exports of both computer services and business services exceeded exports of pharmaceutical products in value terms.

In that year, these three sectors, along with organic chemicals, accounted for over half of Ireland’s total exports. If we throw in insurance & financial services, food & beverages and office & data processing machinery, the proportion rises to almost three quarters. If one were seeking the key to Ireland’s international competitiveness, one should be looking at why these seven very disparate sectors are able to use Ireland as a successful base for serving external markets.

But this would require some real research. Instead, our economists reach for simplistic and largely irrelevant statistics which are both readily available and tend to confirm deeply-entrenched prejudices. We got a good example of this in an article on Ireland’s competitiveness by The Irish Times’s chief economics journalist, Dan O’Brien, in the issue of February 4 last. While acknowledging that there are many ways of measuring competitiveness and that the National Competitiveness Council employs more than 100 competitiveness indicators in its annual reports,O’Brien then devotes most of the rest of his article to the old diehards – prices and labour costs.

Irish economists have an extraordinary tendency to rely on the EU’s harmonised index of consumer prices (HICP) as a measure of competitiveness, even though its relevance to Ireland’s export competitiveness is not immediately obvious – it is hard to see what bearing the price of a meal or a CD player has on the competitiveness of the organic chemicals or software sectors. Nevertheless, O’Brien regards the fact that Ireland’s HICP fell relative to the rest of the EU between late 2008 and early 2010 as evidence of Ireland “regaining” competitiveness.

O’Brien then suggests that trends in economy-wide unit labour costs (the ratio of wages to net output) are a better indication of Ireland’s improved competitiveness. However, the fact is that the vast majority of the Irish workforce are not engaged in export activity and, again, it is hard to see how the unit labour costs of a waitress or CD player salesperson have a bearing on the competitiveness of the main export sectors identified above. While Ireland’s economy-wide unit labour costs have tended to rise relative to the rest of the EU over the last ten years, the opposite has been the case in unit labour costs in manufacturing, the great bulk of whose output is exported. Yet, while the latter are to be found in the same page in the OECD website as the former, they are rarely, if ever, quoted by Irish economists.

There are no comparable data for export services, but the Forfás Economic Impact surveys indicate that payroll costs as a proportion of value added in foreign-owned export services (which account for 95% of the total) fell from 19% in 2000 to 9% in 2008 – a fall of over 50% in unit labour costs.

This is not to say that labour costs are important (never mind crucial) in the competitiveness of Ireland’s main export sectors. If general labour costs were a key determinant of competitiveness, then one should expect exports in all sectors to be influenced by labour cost trends. However, Ireland’s main export sectors have been very variable in their export performance, and there is no evidence that this variability has been influenced in any way by labour cost trends. Between 2000-2006 (the last year for which the relevant data are available), the chemicals & pharmaceuticals sector experienced volume output growth of 50%, despite a rise of 50% in the share of costs accounted for by pay (up from 12.6% to 18%). In the electronic components sector, there was a more modest rise in the labour share of costs from a lower base (up from 13.1% to 16.4%) yet production volume fell by 7%. In the office machines and computers sector, a fall in labour’s already very low share of total costs (down from 4.1% to 3.5%) produced volume growth of 22% - much more modest than that experienced by chemicals & pharmaceuticals.

The key point is that the idea of Ireland Inc. gaining or losing competitiveness is meaningless. Ireland’s exports are dominated by a small number of sectors whose characteristics are extremely varied and whose export performances are equally varied. Adding up these performances and then concluding from the total that Ireland is becoming more or less competitive is pointless. Over the last ten years Ireland has experienced strong export growth in a range of export services, and in pharmaceuticals and medical devices, modest growth in chemicals, and, overall, a sharp fall in exports of electronics hardware. A wide range of factors account for this export variability, of which labour costs play, at most, a minor role. In compiling its Global Competitiveness Index, the World Economic Forum employes no less than 113 quantitative criteria; in Ireland’s case labour cost factors account for less than two per cent of the total value of the competitiveness index.

The economists’ disconnect from the real world is nicely demonstrated from a passage towards the end of Dan O’Brien’s article. Referring to evidence that average productivity in Ireland has been raised by the collapse of the low-productivity construction sector, he suggested as an example that “a bricklayer produces less than the average assembly-line worker or office drone (sic)”. Productivity in the construction industry is indeed low when compared with manufacturing or business services, but O’Brien’s choice of bricklayers for his example was surely unfortunate. Assuming that earnings bear some relationship to productivity, in 2006, when industrial production workers were earning €601 per week, clerical and secretarial workers €540 and administrative civil servants €819, the average weekly earnings of all skilled construction workers came to €877 and there was one report of bricklayers at that stage earning over €3000 per week! The company making these payments was also reportedly paying its Turkish labourers €2.50 per hour. They might have been a better choice for O’Brien’s example.

Tuesday, 15 February 2011

'Job Pact', not 'Competitiveness Pact'

Tom McDonnell: Useful post (here) from Andrew Watt. He looks at the latest uninspiring growth figures in Europe (0.3% quarter-on-quarter in the euro area and just 0.2% in the wider EU27). We cannot assume such anaemic growth will be improved upon as austerity bites down in 2011. Weak employment growth will be the upshot.

One interesting point relates to the newly fashionable idea that increased ‘competitiveness’ is the solution to the jobs crisis. Andrew notes that the Euro area has actually maintained a balanced trade account virtually throughout its existence and achieved a trade surplus in 2010. If the Euro area had a severe competitiveness problem it would surely be reflected in the trade statistics.

Ireland of course has the second highest (http://www.finfacts.ie/irishfinancenews/article_1021642.shtml) trade surplus in the whole of the EU. Ireland has many problems but competitiveness does not appear to be at the top of the list. Worth bearing in mind as the attacks on the minimum wage and other wage floors continue...

One interesting point relates to the newly fashionable idea that increased ‘competitiveness’ is the solution to the jobs crisis. Andrew notes that the Euro area has actually maintained a balanced trade account virtually throughout its existence and achieved a trade surplus in 2010. If the Euro area had a severe competitiveness problem it would surely be reflected in the trade statistics.

Ireland of course has the second highest (http://www.finfacts.ie/irishfinancenews/article_1021642.shtml) trade surplus in the whole of the EU. Ireland has many problems but competitiveness does not appear to be at the top of the list. Worth bearing in mind as the attacks on the minimum wage and other wage floors continue...

Thursday, 10 February 2011

Who benefits?

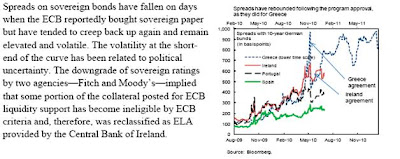

Michael Burke: This is from the IMF’s latest Interim Staff Report (in effect making sure the Dublin government is doing as it’s told). To quote one section of the IMF Report: [click to enlarge]

Two points:

• According to IMF, Irish yields have only been falling because the ECB have been buying bonds- other market participants don’t want to touch them (as of yesterday 10yr yields are back over 9% and closing in on the previous high). This deal is making any future market access less, not more likely

• The chart shown is the IMF’s and suggests that Irish debt yields are going the same way as Greece did after its EU/IMF programme was announced

Market yields reflect an underlying truth. Ireland is becoming less creditworthy as its resources are depleted. This economy is no being bailed out- if it were yields would be falling as the outlook improved. Irish taxpayers are bailing out EU banks – and the outlook is deteriorating because of it.

Two points:

• According to IMF, Irish yields have only been falling because the ECB have been buying bonds- other market participants don’t want to touch them (as of yesterday 10yr yields are back over 9% and closing in on the previous high). This deal is making any future market access less, not more likely

• The chart shown is the IMF’s and suggests that Irish debt yields are going the same way as Greece did after its EU/IMF programme was announced

Market yields reflect an underlying truth. Ireland is becoming less creditworthy as its resources are depleted. This economy is no being bailed out- if it were yields would be falling as the outlook improved. Irish taxpayers are bailing out EU banks – and the outlook is deteriorating because of it.

Tuesday, 8 February 2011

Credit cards in December

An Saoi: The Central Bank provides an analysis of credit cards as part of its monthly statistical report. It is the very final Table in the monthly report. It is of interest because expenditure on credit cards follows the trend of movement in retail sales, excluding motor vehicles (a person is unlikely to buy a car on a credit card.).

The December figures don't disappoint, and reflect the trend CSO estimates for December (Table 2). Helpfully, the report provides a split between cards held personally and those held for business purposes. The new expenditure on business cards is holding steady, but expenditure on personal cards fell by 11.3% against December 2009 & 27.5% against December 2007, when the Irish recession was getting going. Seamus Coffey has a vey good review, complete with numerous graphs, of the December retail sales available here.

The report also shows an extraordinary decline in the number of personal credit cards issued in Ireland, a drop of 36,000 cards in just one month and a drop of 103,000 in the last twelve, leaving just 2,072,000 in use, still a huge number by continental European standards. This fall is significant in itself as it reflects the closing off of access to short-term borrowing for a very large number of people.

New personal expenditure on the cards has fallen back to the levels of December 2004 and indebtedness is also falling albeit at an excruciatingly slow pace. The balance outstanding (owed) is now “just” 3.37 times the monthly expenditure

It would be interesting to know how many of the cards were cancelled by the issuer or voluntarily handed back. Also how much outstanding debt was written off or converted or “consolidated” into loans on cancellation.

However if we look at the trend, then it is clear that activity in the economy will continue to fall for sometime yet. Credit cards are used by many Irish people for their regular out of pocket purchases. This is called "Froopp" in the language of Eurostat (Frequent Out Of Pocket Purchases), which represent a large proportion of personal expenditure. A drop in credit card activity represents a decline in overall consumer activity. A decline in credit card numbers represents a serious decline in the confidence levels of both the issuing banks and consumers for the future.

Credit card spending is not restricted by weather, indeed bad weather is a boon for internet shopping, for which a credit card is a pre-requisite. The bad weather should be reflected by greater use of credit cards, not less as people used the internet instead of venturing from their homes.

Unless we see some upturn in the domestic economy very soon, the Central Bank's recent gloomy forecasts will begin to look overly optimistic.

The December figures don't disappoint, and reflect the trend CSO estimates for December (Table 2). Helpfully, the report provides a split between cards held personally and those held for business purposes. The new expenditure on business cards is holding steady, but expenditure on personal cards fell by 11.3% against December 2009 & 27.5% against December 2007, when the Irish recession was getting going. Seamus Coffey has a vey good review, complete with numerous graphs, of the December retail sales available here.

The report also shows an extraordinary decline in the number of personal credit cards issued in Ireland, a drop of 36,000 cards in just one month and a drop of 103,000 in the last twelve, leaving just 2,072,000 in use, still a huge number by continental European standards. This fall is significant in itself as it reflects the closing off of access to short-term borrowing for a very large number of people.

New personal expenditure on the cards has fallen back to the levels of December 2004 and indebtedness is also falling albeit at an excruciatingly slow pace. The balance outstanding (owed) is now “just” 3.37 times the monthly expenditure