Tuesday, 28 February 2012

Referendum on the Austerity Pact

Tom Healy: With at least one Referendum on the Austerity Pact imminent over the coming months one looks forward in hope to a debate that will draw on values, facts, evidence and reasoned analysis. We can look forward to discussions on cyclically adjusted current balance. Macroeconomics may yet flourish. It would be interesting to hear from at least one macroeconomist anywhere who thinks that the Pact makes economic sense. The debate will be, rather, about choices and options.

Monday, 27 February 2012

As 'austerity' isn't working, what's the alternative?

Michael Burke: Tom Healey has made some very good points in debunking the myth that ‘austerity’ is working. In general the EU governments that have embraced the ‘austerity’ model – the transfer of incomes from labour and the poor to capital and the rich – are currently engaged in a game of blame the foreigner. The economic argument is that it is the turmoil in the EU which has caused the respective slowdowns. The British government repeats this mantra endlessly, even though British growth in 2011 was half of that both in the Euro Area and in EU as a whole.

The ESRI repeats this misdirected criticism. As the latest quarterly report shows, the growth rate of GDP was 0.9% in 2011. The Euro Area economy and the EU economy growth rates were significantly higher in 2011, at 1.5% and 1.6% respectively. Irish exports grew by 4.4% in 2011, according to ESRI projections. If they are right, exports will have risen by approximately €7bn last year in real terms. Without that rise GDP would have fallen by 3.5% in 2011. Clearly, the idea that the EU is the cause of the renewed Irish contraction is a fiction.

The actual cause of the renewed downturn is the policy of ‘austerity’. Household spending, government spending and investment (Gross Fixed Capital Formation) all reached new lows in the Q3 2011 national accounts data. The biggest single contributor remains the decline in investment. On an annualised basis investment has fallen by €26bn in the course of the recession (although it actually began before GDP ell). This compares to a decline of €17bn in GDP and €23.4bn in GNP. Declining investment accounts for more than the entire downturn.

For most Irish business this is entirely logical. Their two main customers are either the good or services they supply to government, or to the household sector. If both these sectors are cutting their own spending, why would businesses invest?

But this is not to say there is no capacity to invest, or to repeat the foolish mantra that “there is no money left”. In 2010, even as the economy was contracting by 0.4%, the Gross Operating Surplus (akin to profits) of Irish businesses rose to €71.2bn from €69.4bn in 2009 in nominal terms. Yet investment fell from €25.3bn to €19bn. Clearly there is plenty of money left. In fact, the entire contraction in both the economy and in investment could be made good just by accessing a proportion of those profits.

If the logjam of business’ unwillingness to invest is broken by higher growth, they will then willingly invest on their own account. All that is required is to break the logjam, which means the government taking control of some of those profits to invest them.

These temporary measures could be labelled windfall taxes, solidarity taxes, an ‘all in this together levy’ or whatever. But the money is there, and growing. Businesses are refusing to invest the profits they are generating. Government action is needed to reallocate these corporate savings towards investment. None of this contradicts the impositions of the Troika, as the terms Gross Operating Surplus or profits aren’t even mentioned in all the documents, bilateral arrangements, MoUs etc.

This is an Irish solution to the crisis. A national recovery based on the resources that are in this economy, and not beholden to foreign powers.

The ESRI repeats this misdirected criticism. As the latest quarterly report shows, the growth rate of GDP was 0.9% in 2011. The Euro Area economy and the EU economy growth rates were significantly higher in 2011, at 1.5% and 1.6% respectively. Irish exports grew by 4.4% in 2011, according to ESRI projections. If they are right, exports will have risen by approximately €7bn last year in real terms. Without that rise GDP would have fallen by 3.5% in 2011. Clearly, the idea that the EU is the cause of the renewed Irish contraction is a fiction.

The actual cause of the renewed downturn is the policy of ‘austerity’. Household spending, government spending and investment (Gross Fixed Capital Formation) all reached new lows in the Q3 2011 national accounts data. The biggest single contributor remains the decline in investment. On an annualised basis investment has fallen by €26bn in the course of the recession (although it actually began before GDP ell). This compares to a decline of €17bn in GDP and €23.4bn in GNP. Declining investment accounts for more than the entire downturn.

For most Irish business this is entirely logical. Their two main customers are either the good or services they supply to government, or to the household sector. If both these sectors are cutting their own spending, why would businesses invest?

But this is not to say there is no capacity to invest, or to repeat the foolish mantra that “there is no money left”. In 2010, even as the economy was contracting by 0.4%, the Gross Operating Surplus (akin to profits) of Irish businesses rose to €71.2bn from €69.4bn in 2009 in nominal terms. Yet investment fell from €25.3bn to €19bn. Clearly there is plenty of money left. In fact, the entire contraction in both the economy and in investment could be made good just by accessing a proportion of those profits.

If the logjam of business’ unwillingness to invest is broken by higher growth, they will then willingly invest on their own account. All that is required is to break the logjam, which means the government taking control of some of those profits to invest them.

These temporary measures could be labelled windfall taxes, solidarity taxes, an ‘all in this together levy’ or whatever. But the money is there, and growing. Businesses are refusing to invest the profits they are generating. Government action is needed to reallocate these corporate savings towards investment. None of this contradicts the impositions of the Troika, as the terms Gross Operating Surplus or profits aren’t even mentioned in all the documents, bilateral arrangements, MoUs etc.

This is an Irish solution to the crisis. A national recovery based on the resources that are in this economy, and not beholden to foreign powers.

Friday, 24 February 2012

'Austerity is working' - not

Tom Healy: In its latest Quarterly Economic Commentary the ESRI QEC authors observe that 'The euro zone economy is slipping into recession due to the impact of both the austerity measures and the effect of policy uncertainty in the euro zone on investment, consumer spending and employment.'

Nothing surprising there. Most commentators expect a flatlining in the EZ economy at best and a new recession at worst - thanks to a combination of factors including coordinated pan-European fiscal austerity. The QEC goes on to say that

'The austerity measures currently being undertaken, and those implemented over the past four years, are having an impact, as evidenced by the improvement in the public finances. However, while these measures correct the public finances they have a dampening effect on economic activity.'

Following €25bn in discretionary fiscal adjustments since 2008 the public sector deficit is still above 10% of GDP, down from 11.8% previously.

Evidence that it is dampening economic activity is the projection by the QEC that private consumer spending will decline in real terms of 1.8% this year and invetment will decline by 3.3%. No hope there for a turnround in the domestic economy any time soon. The QEC projects a further contraction in the domestic economy in 2013. Contrast that with the latest Economic and Fiscal Outlook by the Department of Finance in November which had no volume change in private consumer spending and a 3.2% increase in investment in 2013. It will be argued that the slowdown in internatinal trade explains the downgrading of economic forceasts more generally. But the truth is that the domestic economy is continuing to contract at a faster rate than had been forecasted and all the signals are that fiscal austerity in recent Budgets have driven that decline.

But, the QEC comments as do most economic commentators at least within Ireland that 'there is no other way':

There are very few policy options open to the government to stimulate growth as the traditional instruments of macro policy are either not available (monetary and exchange rate policy) or completely constrained (fiscal policy).

This line is accepted uncritically by most mainstream economic and media commentators. Next month a new economic research institute established under the umbrella of the ICTU will challenge that view and propose an alternative focussed on growth-enhancing strategic investment in much-needed infastructural development.

Nothing surprising there. Most commentators expect a flatlining in the EZ economy at best and a new recession at worst - thanks to a combination of factors including coordinated pan-European fiscal austerity. The QEC goes on to say that

'The austerity measures currently being undertaken, and those implemented over the past four years, are having an impact, as evidenced by the improvement in the public finances. However, while these measures correct the public finances they have a dampening effect on economic activity.'

Following €25bn in discretionary fiscal adjustments since 2008 the public sector deficit is still above 10% of GDP, down from 11.8% previously.

Evidence that it is dampening economic activity is the projection by the QEC that private consumer spending will decline in real terms of 1.8% this year and invetment will decline by 3.3%. No hope there for a turnround in the domestic economy any time soon. The QEC projects a further contraction in the domestic economy in 2013. Contrast that with the latest Economic and Fiscal Outlook by the Department of Finance in November which had no volume change in private consumer spending and a 3.2% increase in investment in 2013. It will be argued that the slowdown in internatinal trade explains the downgrading of economic forceasts more generally. But the truth is that the domestic economy is continuing to contract at a faster rate than had been forecasted and all the signals are that fiscal austerity in recent Budgets have driven that decline.

But, the QEC comments as do most economic commentators at least within Ireland that 'there is no other way':

There are very few policy options open to the government to stimulate growth as the traditional instruments of macro policy are either not available (monetary and exchange rate policy) or completely constrained (fiscal policy).

This line is accepted uncritically by most mainstream economic and media commentators. Next month a new economic research institute established under the umbrella of the ICTU will challenge that view and propose an alternative focussed on growth-enhancing strategic investment in much-needed infastructural development.

Wednesday, 22 February 2012

The false economy of selling state assets to fund job creation

Sinéad Pentony: Today’s announcement provides us with some more details on the government’s thinking in relation to the role of state assets in our economy. The position has become more nuanced in some regards, as the sale of the ESB appears to the off the table (with the exception of some power generators) along with the sale of Bord Gais’s transmission and distribution systems. However, privatisation remains a clear policy focus for the government and a bitter pill is being sweetened with the promise of the proceeds of privatisation being used to fund job creation. But this is false economy.

We are hearing a lot about supporting job creation at the moment. Last week it was the Action Plan for Jobs, this week the sale of state assets will be used to support job creation and tomorrow the government will launch its Pathways to Work - the Government Policy Statement on Labour Market Activation.

Last week's TASC report on the Strategic Role of State Assets, along with today’s statement, clearly articulate the trade-off between short term and longer term investment priorities, with the latter increasing the capacity of the economy to grow and compete with other advanced knowledge-based economies. So the sale of strategic assets is a critical issue because it could actually cost us jobs in the medium-long term if we don’t have the infrastructure that facilitates and supports the functions of a dynamic advanced economy competing globally.

Last week the Action Plan for Jobs was announced. Any initiative aimed at promoting job creation is to be welcomed, and the focus of the Plan is on improving the conditions for doing business in Ireland. While ‘bold ambitions’ are to be admired, it’s difficult to see how the target of increasing the number of people in work by 100,000 – from 1.8 million to 1.9 million jobs by 2016 - can be realised, when the next three budgets are expected to take a further €9 billion out of the economy by 2016. One can only imagine the sorry state that the country will be in, in three years time - if we continue on the current path of austerity piled on top of more austerity.

On Monday night the Frontline programme was devoted to discussing the Action Plan. One of the panellists was businesswoman Glenna Lynch whose business has been struggling since the onset of the crisis and she has been forced to let people go. When asked what she thought about the Action Plan, she said that there was very little in it for her and that the problems she faces relate to the fact that successive austerity budgets are sucking money, demand and confidence out of the economy.

Pathways to Work is being launched tomorrow, the objective of which is to “drive the introduction of measures to improve the conditions for job creation across the economy and to ensure that the creation of these jobs feeds into a reduction in unemployment”. Our labour market activation policies have long been in need of reform, and they must reflect the complexities of the labour market in a modern economy.

In general the Action Plan for Jobs and Pathways to Work can be described as ‘supply-side’ measures, aimed at creating the conditions for businesses to create jobs and for people to be in a position to the take up jobs.

But how can businesses create jobs when the demand for their goods and services is static or shrinking because of budgetary measures?

What’s needed are a series of ‘demand-side’ measures aimed at creating demand for labour, and this requires investment. But this investment should not be financed from the sale of state assets, which should rather be used to support investment in the medium term. Instead, much needed short-term investment should be financed through the €4.7billion remaining in the NPRF, along with an initiative that allows part of the €5.3 billion held by Irish pension funds to be invested in infrastructural projects.

We are hearing a lot about supporting job creation at the moment. Last week it was the Action Plan for Jobs, this week the sale of state assets will be used to support job creation and tomorrow the government will launch its Pathways to Work - the Government Policy Statement on Labour Market Activation.

Last week's TASC report on the Strategic Role of State Assets, along with today’s statement, clearly articulate the trade-off between short term and longer term investment priorities, with the latter increasing the capacity of the economy to grow and compete with other advanced knowledge-based economies. So the sale of strategic assets is a critical issue because it could actually cost us jobs in the medium-long term if we don’t have the infrastructure that facilitates and supports the functions of a dynamic advanced economy competing globally.

Last week the Action Plan for Jobs was announced. Any initiative aimed at promoting job creation is to be welcomed, and the focus of the Plan is on improving the conditions for doing business in Ireland. While ‘bold ambitions’ are to be admired, it’s difficult to see how the target of increasing the number of people in work by 100,000 – from 1.8 million to 1.9 million jobs by 2016 - can be realised, when the next three budgets are expected to take a further €9 billion out of the economy by 2016. One can only imagine the sorry state that the country will be in, in three years time - if we continue on the current path of austerity piled on top of more austerity.

On Monday night the Frontline programme was devoted to discussing the Action Plan. One of the panellists was businesswoman Glenna Lynch whose business has been struggling since the onset of the crisis and she has been forced to let people go. When asked what she thought about the Action Plan, she said that there was very little in it for her and that the problems she faces relate to the fact that successive austerity budgets are sucking money, demand and confidence out of the economy.

Pathways to Work is being launched tomorrow, the objective of which is to “drive the introduction of measures to improve the conditions for job creation across the economy and to ensure that the creation of these jobs feeds into a reduction in unemployment”. Our labour market activation policies have long been in need of reform, and they must reflect the complexities of the labour market in a modern economy.

In general the Action Plan for Jobs and Pathways to Work can be described as ‘supply-side’ measures, aimed at creating the conditions for businesses to create jobs and for people to be in a position to the take up jobs.

But how can businesses create jobs when the demand for their goods and services is static or shrinking because of budgetary measures?

What’s needed are a series of ‘demand-side’ measures aimed at creating demand for labour, and this requires investment. But this investment should not be financed from the sale of state assets, which should rather be used to support investment in the medium term. Instead, much needed short-term investment should be financed through the €4.7billion remaining in the NPRF, along with an initiative that allows part of the €5.3 billion held by Irish pension funds to be invested in infrastructural projects.

The EU-IMF Deal Does Not Require Privatisation

Michael Taft: Whatever about the case-by-case merits of the Government’s announcement today regarding the sell-off of state assets, we should be clear: the EU-IMF Memorandum of Understanding does not require privatisation, in whole or in part. In addition, the discussion of the sale of state assets in the Memorandum does not take place in the fiscal section but rather in the section regarding obstacles to competitiveness. In other words, if there is to be a sale of state assets, the objective is not to write down debt but to improve competitiveness. Indeed, it is hardly likely that the Troika would demand that state assets be sold in order to reduce the projected debt of 115 percent in 2015 down to 114 percent (which is what the Government’s announcement today would do).

The quarterly reviews conducted by the Troika make it clear that the provision for selling state assets did not come from them – it came from the Government and its Programme for Government. And it was Fine Gael that was the driver of the privatisation provision in the Programme – Labour campaigned against privatisation in the last general election.

What we have had is an elaborate choreography around the issue of privatisation, shifting blame and inventing targets which have had the effect of obfuscating the issue. Nonetheless, this should not blind us to where the demand for privatisation is coming from. Senator Shane Ross, writing about the meeting between the Troika and the Technical Group of TDs, reported this exchange on the subject:

‘The troika delegates insisted that they had not prescribed any privatisations. They wanted to see certain semi-states "restructured" and competition in the market. Contrary to media perceptions, they were not pressing the Government to raise any specific amount from the sale of State assets. The figures in the public arena of between €2bn and €6bn did not come from them.’

That this is confirmed by Sinn Fein, from their meeting with the Troika, only reinforces this point.

The demand for privatisation – and the paying down of debt – does not come from the Troika. It comes from our own Government.

For a detailed overview of this issue you can read this post I wrote back in October.

The quarterly reviews conducted by the Troika make it clear that the provision for selling state assets did not come from them – it came from the Government and its Programme for Government. And it was Fine Gael that was the driver of the privatisation provision in the Programme – Labour campaigned against privatisation in the last general election.

What we have had is an elaborate choreography around the issue of privatisation, shifting blame and inventing targets which have had the effect of obfuscating the issue. Nonetheless, this should not blind us to where the demand for privatisation is coming from. Senator Shane Ross, writing about the meeting between the Troika and the Technical Group of TDs, reported this exchange on the subject:

‘The troika delegates insisted that they had not prescribed any privatisations. They wanted to see certain semi-states "restructured" and competition in the market. Contrary to media perceptions, they were not pressing the Government to raise any specific amount from the sale of State assets. The figures in the public arena of between €2bn and €6bn did not come from them.’

That this is confirmed by Sinn Fein, from their meeting with the Troika, only reinforces this point.

The demand for privatisation – and the paying down of debt – does not come from the Troika. It comes from our own Government.

For a detailed overview of this issue you can read this post I wrote back in October.

Thursday, 16 February 2012

TASC issues new report on State Assets

Click here to download TASC's new report, The Strategic Role of State Assets - Reframing the Privatisation Debate. Comments?

Wednesday, 15 February 2012

Karl Whelan's briefing paper for Oireachtas Finance Committee

Karl Whelan, Brian Lucey and Stephan Kinsella are appearing before the Oireachtas Finance Committee this afternoon to discuss ELA and promissory notes. Click here for links to Prof Whelan's briefing paper and opening remarks.

Tuesday, 14 February 2012

A taxing fable

David Jacobson: In Monday’s Irish Times business editor John McManus speculated about why there had not been more response from disgruntled, low-earning tax payers to the government tax-cut for the rich. This is the tax relief on 30 per cent of earnings between €75,000 and €500,000 of foreign employees of multinationals transferring to Ireland for the medium term. Among other explanations, he suggested “fatigue”, “restraint” and “social cohesion”. Here is the truth:

There is a religion in Ireland the main mantra of which is “12.5 per cent corporate profit tax rate”. The elaborate accoutrements of the religion involve doing anything that the multinationals require, or claim that they require, and avoiding anything that could be interpreted to be troubling them. The high priests of the religion are the IDA. Among the staunch upholders of the religion are tax advisers, who are paid far more than the state receives in tax from multinationals.

Now it came to pass that a tax adviser and an executive from a multinational were having lunch (not free, of course). They came up with the idea of getting more net pay for multinational executives and worked out a plan as to how to justify this to the high priests. “We can tell them that it will be narrow and focused, but will encourage more job creation” said the tax adviser. “But once the measure has been passed, we’ll find loopholes and other ways to extend it.”

They then proposed it to the high priests, who saw it in terms of zeal in support of what they propagate, and in turn decided to sell the idea to the state. There is apparent separation of church and state in Ireland, of course, but there is not a member of the government who would admit publicly to being even agnostic about, never mind against, the religion’s main mantra.

The government thus, naturally, accepted the proposal. It has been accepted by the instruments of the media, both those in favour and critical of government, because of the risks involved in contradicting the fundamental dogma of the religion. And the people of the state, with no leadership into alternative paths, have also gone along with it.

And that is the true story of why the low-earning tax payers of Ireland have accepted the proposal to cut taxes for the rich.

There is a religion in Ireland the main mantra of which is “12.5 per cent corporate profit tax rate”. The elaborate accoutrements of the religion involve doing anything that the multinationals require, or claim that they require, and avoiding anything that could be interpreted to be troubling them. The high priests of the religion are the IDA. Among the staunch upholders of the religion are tax advisers, who are paid far more than the state receives in tax from multinationals.

Now it came to pass that a tax adviser and an executive from a multinational were having lunch (not free, of course). They came up with the idea of getting more net pay for multinational executives and worked out a plan as to how to justify this to the high priests. “We can tell them that it will be narrow and focused, but will encourage more job creation” said the tax adviser. “But once the measure has been passed, we’ll find loopholes and other ways to extend it.”

They then proposed it to the high priests, who saw it in terms of zeal in support of what they propagate, and in turn decided to sell the idea to the state. There is apparent separation of church and state in Ireland, of course, but there is not a member of the government who would admit publicly to being even agnostic about, never mind against, the religion’s main mantra.

The government thus, naturally, accepted the proposal. It has been accepted by the instruments of the media, both those in favour and critical of government, because of the risks involved in contradicting the fundamental dogma of the religion. And the people of the state, with no leadership into alternative paths, have also gone along with it.

And that is the true story of why the low-earning tax payers of Ireland have accepted the proposal to cut taxes for the rich.

Guest post by Martin O'Dea: Rebalancing the power

Martin O'Dea lectures in Management and Human Resource Management at the Dublin Business School: There are many levels at which to assess the current financial crisis in Europe. One of those at the higher level involves the discord between political bodies and financial markets and how this power battle is playing out. There has been talk of financial transaction taxes from Angela Merkel and finance ministers from Austria and Belgium as well as France. The concept is seen to originate with John Keynes in 1936 and was applied particularly in 1972 by Nobel winning economist Jim Tobin. There have been alterations in the interim as analysts try to find ways to minimise the impact on market activities and to dissuade companies from fleeing to destinations where any such tax does not exist. There seems a reasonable chance developing over the last decade or so that a global financial transaction tax could be employed to attempt to bridge growing income inequality, somewhat, and also to provide a fund to deal with many major social issues; though, of course, this remains to be seen.

European countries have pushed hard for the introduction of a F.T.T. tax since 2008 and, in fact, Sarkozy of France has recently introduced a 0.1% on certain transactions (though not on bonds) in the hope that others will follow. The G20 did not reach agreement on a universal Tobin Tax, and so Europe proposed to move ahead within its own ‘borders’. The proposed E.U. F.T.T. will apply to the country where the financial operator is based, and so for example a German bank could not avoid the tax by having transactions take place from a different base. The U.K., despite two-thirds support for this type of tax among its citizens has opted out, and so the outcome of this issue remains unresolved. In as much as the ‘market’ can be seen as a singular entity, there must be disquiet at this concept and some of the negotiations around indebted sovereigns must hinge on some brinkmanship in this battle. The investors and fund managers, in the most, whose jobs entail achieving maximum return for their clients will naturally look at this tax as an unwelcome proposal for their balance sheets. They also look at burden sharing on debts in a similar way

It is easy enough to feel that the markets have all the cards here – it is certainly what the Irish government state quite openly; i.e. that they have no choice but to follow instructions from the ECB and commission and that they are behaving in the only way that they can as markets would not allow any deviation; and so ‘Armageddon’, ‘bombs going off’ etc is the language that is suggested if we force the issue of debt clearance with Europe or if Europe generally pushes the issue with the markets.

There is a very strong argument of logic put forward by David McWilliams and others for a long time now that, in fact, this position is inherently wrong, that markets can only invest in what is coming and so would quickly reinvest in countries that shed unbearable debt burdens, because this gives them a chance to grow and makes them more worthy of investment. Iceland seems to provide some support to this argument, as they took a massive hit when declaring bankruptcy and saw fairly immediate growth thereafter as the issues were ‘dealt with’ and the country and economy reeled but then began to move on.

There are obviously many others who say that this is too big a risk and what happens if the speculators bring down the house. It is easy to sit and think, how did we come to this, how did we find ourselves in a system where the markets dictate to the politicians.

The context of all of this is truly of astounding proportions now. Even a cursory glance at twentieth century politico-economic history shows the dangers in economically disenfranchising a people and how when all moderate options point to economic oblivion there is provided a breeding ground for extremism. These arguments seemed extreme themselves just a few years ago, but an objective look at Europe and Greece particularly as well as the local Irish example of incredibly damaging social impositions under the somehow surreal stipulation to pay banking debts with taxpayers money to a value such as currently taking place, one can see the potential hazards. Anger will continue to mount as the drip feeding of the shocks of 3.1 billion to Anglo promissory notes comes again in March and again and again for a decade. And, of course, in the context of a comment from a slightly heady Taosieach at Davos implying that ‘we all went “mad with borrowing”’ and people reel from the frustration that whatever they have borrowed they have to pay back while also covering these banks borrowings, really makes it beyond a serious issue for Europe, and an imperative one for the maintenance of order at this point.

Regarding this seeming stranglehold of the markets then - this is one of the major difficulties, but it can also be the source of the solution, for we seem to have collectively forgotten that politicians (representing us the majority) actually hold the strongest hand. They make the laws. They have national judiciaries, police and militaries ensuring their ability to do so as well as many international fora with domestic popular support to resist the market influence (and if McWilliams etc are right – even the markets themselves would support governments eventually standing up for themselves).

So bearing in mind all of this, what could politicians do? Well, they might put the following financial logic forward to the key financial institutes as matters of fact. It is already planned by the European commission that there will be a financial transaction tax in 2014. It will be 0.1% against the exchange of shares and bonds and 0.01% across derivative contracts. It is forecasted to raise €55 billion per anum. A European treaty must allow governments to tell markets that if massive write downs of government debts are not now taken as we dictate the financial transaction tax will be 0.3% against the exchange of shares and bonds and 0.03% across derivative contracts.

Markets are not really thinking entities; people go to work and do what their bosses wish in an attempt to continue to pay their own mortgages and care for their dependents as well as progress in their own careers. Their bosses pressurise them for return as a means of passing on the systemic pressure that comes on their jobs and performances from shareholders. Shareholders can be a whole myriad of personas often financial institutes themselves and pension, insurance funds etc. So it is clear that markets cannot, as currently constructed, grow social consciences. By definition there is only one motive that markets can comprehend. The future of technological development and better informed and educated populations and the peace and prosperity that can arise from that await resolution of this crisis. The resolution of the crisis awaits massive write down of debts, and in the Irish case the allowing of bankrupt banks to go bankrupt. European leaders must speak the language of the markets but explain in that language that they are in charge and that they will not allow continuing social collapse on their watch.

European countries have pushed hard for the introduction of a F.T.T. tax since 2008 and, in fact, Sarkozy of France has recently introduced a 0.1% on certain transactions (though not on bonds) in the hope that others will follow. The G20 did not reach agreement on a universal Tobin Tax, and so Europe proposed to move ahead within its own ‘borders’. The proposed E.U. F.T.T. will apply to the country where the financial operator is based, and so for example a German bank could not avoid the tax by having transactions take place from a different base. The U.K., despite two-thirds support for this type of tax among its citizens has opted out, and so the outcome of this issue remains unresolved. In as much as the ‘market’ can be seen as a singular entity, there must be disquiet at this concept and some of the negotiations around indebted sovereigns must hinge on some brinkmanship in this battle. The investors and fund managers, in the most, whose jobs entail achieving maximum return for their clients will naturally look at this tax as an unwelcome proposal for their balance sheets. They also look at burden sharing on debts in a similar way

It is easy enough to feel that the markets have all the cards here – it is certainly what the Irish government state quite openly; i.e. that they have no choice but to follow instructions from the ECB and commission and that they are behaving in the only way that they can as markets would not allow any deviation; and so ‘Armageddon’, ‘bombs going off’ etc is the language that is suggested if we force the issue of debt clearance with Europe or if Europe generally pushes the issue with the markets.

There is a very strong argument of logic put forward by David McWilliams and others for a long time now that, in fact, this position is inherently wrong, that markets can only invest in what is coming and so would quickly reinvest in countries that shed unbearable debt burdens, because this gives them a chance to grow and makes them more worthy of investment. Iceland seems to provide some support to this argument, as they took a massive hit when declaring bankruptcy and saw fairly immediate growth thereafter as the issues were ‘dealt with’ and the country and economy reeled but then began to move on.

There are obviously many others who say that this is too big a risk and what happens if the speculators bring down the house. It is easy to sit and think, how did we come to this, how did we find ourselves in a system where the markets dictate to the politicians.

The context of all of this is truly of astounding proportions now. Even a cursory glance at twentieth century politico-economic history shows the dangers in economically disenfranchising a people and how when all moderate options point to economic oblivion there is provided a breeding ground for extremism. These arguments seemed extreme themselves just a few years ago, but an objective look at Europe and Greece particularly as well as the local Irish example of incredibly damaging social impositions under the somehow surreal stipulation to pay banking debts with taxpayers money to a value such as currently taking place, one can see the potential hazards. Anger will continue to mount as the drip feeding of the shocks of 3.1 billion to Anglo promissory notes comes again in March and again and again for a decade. And, of course, in the context of a comment from a slightly heady Taosieach at Davos implying that ‘we all went “mad with borrowing”’ and people reel from the frustration that whatever they have borrowed they have to pay back while also covering these banks borrowings, really makes it beyond a serious issue for Europe, and an imperative one for the maintenance of order at this point.

Regarding this seeming stranglehold of the markets then - this is one of the major difficulties, but it can also be the source of the solution, for we seem to have collectively forgotten that politicians (representing us the majority) actually hold the strongest hand. They make the laws. They have national judiciaries, police and militaries ensuring their ability to do so as well as many international fora with domestic popular support to resist the market influence (and if McWilliams etc are right – even the markets themselves would support governments eventually standing up for themselves).

So bearing in mind all of this, what could politicians do? Well, they might put the following financial logic forward to the key financial institutes as matters of fact. It is already planned by the European commission that there will be a financial transaction tax in 2014. It will be 0.1% against the exchange of shares and bonds and 0.01% across derivative contracts. It is forecasted to raise €55 billion per anum. A European treaty must allow governments to tell markets that if massive write downs of government debts are not now taken as we dictate the financial transaction tax will be 0.3% against the exchange of shares and bonds and 0.03% across derivative contracts.

Markets are not really thinking entities; people go to work and do what their bosses wish in an attempt to continue to pay their own mortgages and care for their dependents as well as progress in their own careers. Their bosses pressurise them for return as a means of passing on the systemic pressure that comes on their jobs and performances from shareholders. Shareholders can be a whole myriad of personas often financial institutes themselves and pension, insurance funds etc. So it is clear that markets cannot, as currently constructed, grow social consciences. By definition there is only one motive that markets can comprehend. The future of technological development and better informed and educated populations and the peace and prosperity that can arise from that await resolution of this crisis. The resolution of the crisis awaits massive write down of debts, and in the Irish case the allowing of bankrupt banks to go bankrupt. European leaders must speak the language of the markets but explain in that language that they are in charge and that they will not allow continuing social collapse on their watch.

Monday, 13 February 2012

Guest post by Arthur Doohan: Loose lips sink ships

Arthur Doohan: The "grown-up's" will remember the opening sequence to the 'Mission Impossible' TV series, where the tape self destructs a few seconds after being played.

I have sad news for you. That technology has not been perfected.

So ... There is no way for Draghi, Barroso, Van Rompuy or Merkozy to make your Euro notes or those in the bank's ATMS disappear in a puff of smoke.

As we teeter on the brink of a possible debt crisis, there is a lot of loose talk flying around about the death of the Euro and about Ireland being thrown out of the "Euro". Such talk is ill-informed, ignorant and, at a time of distress and fear, it is scaremongering, if not actually amounting to "shouting 'Fire!' in a crowded cinema".

Money is …..whatever people deem it to be. In the past money has been: cowrie shells, temple vouchers, unopened packs of "fags" and bits of metal. Today, money is mainly electrons, some paper and a few bits of base metal "dressed as lamb". We worked hard, jointly with our European partners, to re-denominate our money into a jointly held and managed currency called the Euro.

And now, there is nothing, NOTHING, that can stop the Euro being our currency.

Firstly, we are an equal partner in the Target2 payments system that the ECB uses as a clearing house for the Central Banks of the Euro-system to make and receive payments. Further, no authority in either the EU or the ECB has said that anyone can or will be kicked out of the Euro. There is no process for so doing and there can not be under the current treaties. Again, with respect to the currency, there is, quite deliberately and by design, no way of telling a Greek from an Irish from a French Euro.

Secondly, when Argentina defaulted on her US dollar debts it did not stop the dollar being a valid currency in Japan or in the US. It did not stop the majority of Argentinian business being conducted in US dollars. It weakened the Argentinian Peso and made the overall debt burden greater. But that can't happen to us because our debts are denominated in our own currency (the Euro). Even if Ireland decided to default on some of her sovereign obligations, it would make no difference to your usage of the currency or to a German person's usage of it or to the French Government's usage.

Finally, the concept of 'leaving the Euro' is often referred to as some form of solution, as if our troubles would be over if we cast off the yoke of Euro-usage. Nothing could be further from reality and the truth.

If we left the Euro we would have to 1) print and distribute a new currency, 2) institute capital controls (in a vain attempt to stop money leaving the State, and which might now be un-Constitutional), 3)attempt to establish and then defend a value in Euro terms for this currency (with all the interest rate volatility that implies and requires), 4) institute import and export controls in order to prop up the capital controls (with all the extra costs and delays for business that implies).

Further, just who would be leaving the Euro? Probably just the State in terms of redefining exactly what 'legal tender' would be for tax and contract purposes. But the State could not seize the Euros in your bank account and force them to be changed to 'NewPunts' or whatever. So we would become like Argentina with a weak official currency for State and tax related transactions and civil service pay and an external currency (Dollars for them, Euros in our case) for 'real stuff'.

And what would we get in exchange for all that trouble? Only the opportunity to say 'We can't pay you back everything we owe you'.

I am not recommending, in this post, any particular course of action. I just want to see an end to the loose talk and the propagation of fear, uncertainty and doubt as a means for ill informed politicians to bludgeon people into agreeing with them. I have in mind particularly suggestions that our ATMs would 'run dry' if there were to be a default.

To suggest that anyone in Europe would attempt or even think of stopping Irish citizens from buying their daily bread in reaction to a problem created by Irish politicians is to display an ignorance of how such systems work, and to the people and the Commission of the EU.

The Euro is not the problem. The Euro works, and works tremendously well as its endurance of the upheavals and stresses of the last few years have shown.

The design of the 'Growth and Stability Pact' is not the problem. Since it was never enforced (and Germany was the worst and longest rule breaker) it cannot be said to have failed and all of the debt problems we now have are the exact things the GSP was designed to prevent.

The problem is the level of debt some countries are carrying. This is an old problem, and the old answer was always a currency devaluation. Since we all have the same currency now we can't do that. But a debt 'haircut' amounts to the same thing.

So, can we please take a haircut now before we all go bald?

Arthur Doohan is a former banker currently promoting a public policy debate on alternative solutions to the debt crisis in Ireland and to bank restructuring

I have sad news for you. That technology has not been perfected.

So ... There is no way for Draghi, Barroso, Van Rompuy or Merkozy to make your Euro notes or those in the bank's ATMS disappear in a puff of smoke.

As we teeter on the brink of a possible debt crisis, there is a lot of loose talk flying around about the death of the Euro and about Ireland being thrown out of the "Euro". Such talk is ill-informed, ignorant and, at a time of distress and fear, it is scaremongering, if not actually amounting to "shouting 'Fire!' in a crowded cinema".

Money is …..whatever people deem it to be. In the past money has been: cowrie shells, temple vouchers, unopened packs of "fags" and bits of metal. Today, money is mainly electrons, some paper and a few bits of base metal "dressed as lamb". We worked hard, jointly with our European partners, to re-denominate our money into a jointly held and managed currency called the Euro.

And now, there is nothing, NOTHING, that can stop the Euro being our currency.

Firstly, we are an equal partner in the Target2 payments system that the ECB uses as a clearing house for the Central Banks of the Euro-system to make and receive payments. Further, no authority in either the EU or the ECB has said that anyone can or will be kicked out of the Euro. There is no process for so doing and there can not be under the current treaties. Again, with respect to the currency, there is, quite deliberately and by design, no way of telling a Greek from an Irish from a French Euro.

Secondly, when Argentina defaulted on her US dollar debts it did not stop the dollar being a valid currency in Japan or in the US. It did not stop the majority of Argentinian business being conducted in US dollars. It weakened the Argentinian Peso and made the overall debt burden greater. But that can't happen to us because our debts are denominated in our own currency (the Euro). Even if Ireland decided to default on some of her sovereign obligations, it would make no difference to your usage of the currency or to a German person's usage of it or to the French Government's usage.

Finally, the concept of 'leaving the Euro' is often referred to as some form of solution, as if our troubles would be over if we cast off the yoke of Euro-usage. Nothing could be further from reality and the truth.

If we left the Euro we would have to 1) print and distribute a new currency, 2) institute capital controls (in a vain attempt to stop money leaving the State, and which might now be un-Constitutional), 3)attempt to establish and then defend a value in Euro terms for this currency (with all the interest rate volatility that implies and requires), 4) institute import and export controls in order to prop up the capital controls (with all the extra costs and delays for business that implies).

Further, just who would be leaving the Euro? Probably just the State in terms of redefining exactly what 'legal tender' would be for tax and contract purposes. But the State could not seize the Euros in your bank account and force them to be changed to 'NewPunts' or whatever. So we would become like Argentina with a weak official currency for State and tax related transactions and civil service pay and an external currency (Dollars for them, Euros in our case) for 'real stuff'.

And what would we get in exchange for all that trouble? Only the opportunity to say 'We can't pay you back everything we owe you'.

I am not recommending, in this post, any particular course of action. I just want to see an end to the loose talk and the propagation of fear, uncertainty and doubt as a means for ill informed politicians to bludgeon people into agreeing with them. I have in mind particularly suggestions that our ATMs would 'run dry' if there were to be a default.

To suggest that anyone in Europe would attempt or even think of stopping Irish citizens from buying their daily bread in reaction to a problem created by Irish politicians is to display an ignorance of how such systems work, and to the people and the Commission of the EU.

The Euro is not the problem. The Euro works, and works tremendously well as its endurance of the upheavals and stresses of the last few years have shown.

The design of the 'Growth and Stability Pact' is not the problem. Since it was never enforced (and Germany was the worst and longest rule breaker) it cannot be said to have failed and all of the debt problems we now have are the exact things the GSP was designed to prevent.

The problem is the level of debt some countries are carrying. This is an old problem, and the old answer was always a currency devaluation. Since we all have the same currency now we can't do that. But a debt 'haircut' amounts to the same thing.

So, can we please take a haircut now before we all go bald?

Arthur Doohan is a former banker currently promoting a public policy debate on alternative solutions to the debt crisis in Ireland and to bank restructuring

Friday, 10 February 2012

Minimum Essential Budgets

Nat O'Connor: The TCD Policy Institute recently published a volume by the Vincentian Partnership for Social Justice and Dr Micheál Collins, which examines the 'minimum essential' budgets required by different household types. The Vincentians have been working on this kind of study for a number of years, and a copy of the report can be found under publications on budgeting.ie.

I think Dan O'Brien rather unfairly criticises the report in his Irish Times editorial. He argues that taxpayers’ money should not have funded the research, and that "Impartiality and objectivity are hallmarks of academic research. Publishing the views of a lobbyist blurs the line, thereby undermining TCD's credibility."

In fairness, one of the authors, Micheál Collins, was working as an academic member of staff at TCD at the time of receiving the grant. If anything, his work on the report has helped document the method and findings in a more academically rigorous way. Money was not being given to lobbyists, as Dan O'Brien portrays it.

Every piece of research comes from implicit or explicit normative assumptions. What matters is whether or not the method is robust and the evidence is clearly visible so that others can make alternative interpretations of the same data. In fairness to this study, it is based on an established, qualitative method involving focus groups who discuss what they regard as a reasonable standard of living and it does provide quite a lot of detail about the weekly costs they regard as 'minimum' broken down under a range of headings.

This standard of living does involve more than survival and includes a modest degree of "social inclusion and participation". However, Appendix A shows what is involved in minimum social participation remains frugal. For example, the €12.66 per week in a family budget for socialising is based on ten social events per adult each year. The researchers then go to the local shops and services and check out the prices to pay for the list.

What the report highlights is that, unsurprisingly, a great number of people on modest incomes in Ireland do not have an income sufficient to meet a 'minimum essential' budget. In particular, families with children in a number of cases have insufficient incomes. Moreover, it is of concern that a single person working full-time on the minimum wage also cannot afford an essential budget.

However, some households do have sufficient income. For example, a pensioner couple's income from the non-contributory state pension is sufficient to cover their minimum essentials because of the range of other non-cash supports, like fuel allowance, free travel and medical card. That's a useful validation of the welfare system and hardly a 'lobbyist' perspective.

What is missing from the report is a more full exposition of the costs. The publication notes that grocery prices are typically based on the least expensive supermarket 'own brand' items, but we only see aggregates and it would be useful to see item-by-item breakdowns; I imagine that this would be of particular use to the Department of Social Protection and services like MABS who advise people on how to budget their income. It should also be of interest to businesses to see evidence of market niches for cheaper goods and services.

The focus on weekly itemised expenditure is also of value because it highlights in very tangible terms how vulnerable household budgets are to relatively small ‘shocks’, like medical expenses or the costs of a funeral. What happens in reality is that people on low incomes are particularly badly insulated against such one-off expenses and these can lead to the use of moneylenders. In 2007 (latest survey) more than one in five people had difficulty accessing banking facilities (i.e. getting a basic bank account). This gap is filled for people on the lowest incomes by “52 licensed moneylenders in Ireland, 36 of whom operate ‘doorstep collection’ businesses” and who can charge over 150 per cent interest on small loans. See TASC (2010) Life and Debt.

The issue of one-off 'shocks' emphasises the importance of non-cash supports as 'shock-absorbers'; such as the medical card or social housing. These help people to cope with sudden expenses, without having to use up any savings they might have or take a loan. The study also usefully opens the door to more in-depth examination of where non-cash supports can help people get by without getting into debt.

I think Dan O'Brien rather unfairly criticises the report in his Irish Times editorial. He argues that taxpayers’ money should not have funded the research, and that "Impartiality and objectivity are hallmarks of academic research. Publishing the views of a lobbyist blurs the line, thereby undermining TCD's credibility."

In fairness, one of the authors, Micheál Collins, was working as an academic member of staff at TCD at the time of receiving the grant. If anything, his work on the report has helped document the method and findings in a more academically rigorous way. Money was not being given to lobbyists, as Dan O'Brien portrays it.

Every piece of research comes from implicit or explicit normative assumptions. What matters is whether or not the method is robust and the evidence is clearly visible so that others can make alternative interpretations of the same data. In fairness to this study, it is based on an established, qualitative method involving focus groups who discuss what they regard as a reasonable standard of living and it does provide quite a lot of detail about the weekly costs they regard as 'minimum' broken down under a range of headings.

This standard of living does involve more than survival and includes a modest degree of "social inclusion and participation". However, Appendix A shows what is involved in minimum social participation remains frugal. For example, the €12.66 per week in a family budget for socialising is based on ten social events per adult each year. The researchers then go to the local shops and services and check out the prices to pay for the list.

What the report highlights is that, unsurprisingly, a great number of people on modest incomes in Ireland do not have an income sufficient to meet a 'minimum essential' budget. In particular, families with children in a number of cases have insufficient incomes. Moreover, it is of concern that a single person working full-time on the minimum wage also cannot afford an essential budget.

However, some households do have sufficient income. For example, a pensioner couple's income from the non-contributory state pension is sufficient to cover their minimum essentials because of the range of other non-cash supports, like fuel allowance, free travel and medical card. That's a useful validation of the welfare system and hardly a 'lobbyist' perspective.

What is missing from the report is a more full exposition of the costs. The publication notes that grocery prices are typically based on the least expensive supermarket 'own brand' items, but we only see aggregates and it would be useful to see item-by-item breakdowns; I imagine that this would be of particular use to the Department of Social Protection and services like MABS who advise people on how to budget their income. It should also be of interest to businesses to see evidence of market niches for cheaper goods and services.

The focus on weekly itemised expenditure is also of value because it highlights in very tangible terms how vulnerable household budgets are to relatively small ‘shocks’, like medical expenses or the costs of a funeral. What happens in reality is that people on low incomes are particularly badly insulated against such one-off expenses and these can lead to the use of moneylenders. In 2007 (latest survey) more than one in five people had difficulty accessing banking facilities (i.e. getting a basic bank account). This gap is filled for people on the lowest incomes by “52 licensed moneylenders in Ireland, 36 of whom operate ‘doorstep collection’ businesses” and who can charge over 150 per cent interest on small loans. See TASC (2010) Life and Debt.

The issue of one-off 'shocks' emphasises the importance of non-cash supports as 'shock-absorbers'; such as the medical card or social housing. These help people to cope with sudden expenses, without having to use up any savings they might have or take a loan. The study also usefully opens the door to more in-depth examination of where non-cash supports can help people get by without getting into debt.

Tuesday, 7 February 2012

The Fiscal Compact, or: where will we be in 2018?

Tom McDonnell: The debate about the fiscal compact is likely to continue for some time. Much has been made of the 'one twentieth' rule but in practice it is adherence to the rules around the structural balance which will really matter in terms of the fiscal stance post 2015.

Ireland is currently working its way through an Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) which requires the general government deficit to be no worse than 3% of GDP in 2015. At that point Ireland will be expected to improve its structural budget balance by converging to a medium term objective of a deficit no larger than 0.5% of GDP. The Department of Finance estimates that the structural deficit will be 3.7% in 2015. If one generously accepts this figure as accurate then the government will be obliged to adopt a fiscal stance consistent with 'correcting' the remaining gap. This will trigger additional discretionary fiscal consolidation equivalent to circa 3.2% of GDP - about €5 billion in 2012 terms (though not necessarily all in the same year). This suggests that the programme of continuous austerity will continue out to 2017/2018. A bleak prospect.

This continuous fiscal tightening combined with the huge private debt overhang will drag on the economy's capacity to generate increases in real GDP. Debt sustainability in the absence of higher inflation (anathema to the ECB) or low interest rates on government borrowings (perhaps by extending the official programme past 2013) will be challenging. The Treaty does refer to an ability to deviate from the medium term objective under 'exceptional circumstances'. It will be interesting to see how this is interpreted in practice and it is possible there may be scope for wriggle room.

The fiscal compact is certainly no panacea for the current crisis though it might ameliorate the severity of the next one. The answers to the current crisis lie elsewhere.

Ireland is currently working its way through an Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) which requires the general government deficit to be no worse than 3% of GDP in 2015. At that point Ireland will be expected to improve its structural budget balance by converging to a medium term objective of a deficit no larger than 0.5% of GDP. The Department of Finance estimates that the structural deficit will be 3.7% in 2015. If one generously accepts this figure as accurate then the government will be obliged to adopt a fiscal stance consistent with 'correcting' the remaining gap. This will trigger additional discretionary fiscal consolidation equivalent to circa 3.2% of GDP - about €5 billion in 2012 terms (though not necessarily all in the same year). This suggests that the programme of continuous austerity will continue out to 2017/2018. A bleak prospect.

This continuous fiscal tightening combined with the huge private debt overhang will drag on the economy's capacity to generate increases in real GDP. Debt sustainability in the absence of higher inflation (anathema to the ECB) or low interest rates on government borrowings (perhaps by extending the official programme past 2013) will be challenging. The Treaty does refer to an ability to deviate from the medium term objective under 'exceptional circumstances'. It will be interesting to see how this is interpreted in practice and it is possible there may be scope for wriggle room.

The fiscal compact is certainly no panacea for the current crisis though it might ameliorate the severity of the next one. The answers to the current crisis lie elsewhere.

Friday, 3 February 2012

January 2012 tax - have we reached the bottom?

An Saoi: The January tax figures have given the Government a bit of good news, but the question is how much?

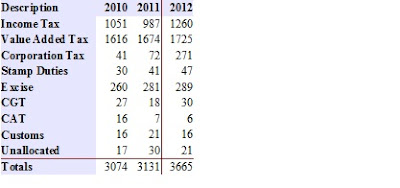

The Table below gives the figures for January from 2010 to 2012 and superficially the figures look like a big improvement and certainly some particular tax heads look particularly good.

The Income Tax is well ahead over previous years mainly because the payments relate to 2011 and are influenced by the Brian Lenihan changes and weekly paid staff had an additional payday in December, a Week 53, which added to the tax yield. The income tax figures for the last four months of 2011 were well behind target and perhaps there is a degree of balancing payments being submitted with forms P35. The weakness of Income Tax in 2011 may have been overstated and was perhaps a cashflow issue for employers.

The Corporation Tax figure must be a serious worry to the Government. It includes €261M which they told us really belonged in December 2011 but arrived late. This suggests that the net figure for January was just €10M. It will be May before enough is known to hazard a guess at the final outcome.

Value Added Tax is up €51M on the same period and reflects the better weather in November and December 2011 over the previous year and perhaps a degree of shopping ahead of the increase in the standard rate of VAT which took effect from 1st January. The Retail Sales Figures released by the CSO suggest that the motor trade performed strongly in December. The slight increase in Excise Figures confirms this also.

The other taxes, even together, do not amount to very much and are not really worth a comment for a few more months. It will be March before we can see a definite trend, but on these figures, the Government has a chance of reaching its targets.

The Table below gives the figures for January from 2010 to 2012 and superficially the figures look like a big improvement and certainly some particular tax heads look particularly good.

The Income Tax is well ahead over previous years mainly because the payments relate to 2011 and are influenced by the Brian Lenihan changes and weekly paid staff had an additional payday in December, a Week 53, which added to the tax yield. The income tax figures for the last four months of 2011 were well behind target and perhaps there is a degree of balancing payments being submitted with forms P35. The weakness of Income Tax in 2011 may have been overstated and was perhaps a cashflow issue for employers.

The Corporation Tax figure must be a serious worry to the Government. It includes €261M which they told us really belonged in December 2011 but arrived late. This suggests that the net figure for January was just €10M. It will be May before enough is known to hazard a guess at the final outcome.

Value Added Tax is up €51M on the same period and reflects the better weather in November and December 2011 over the previous year and perhaps a degree of shopping ahead of the increase in the standard rate of VAT which took effect from 1st January. The Retail Sales Figures released by the CSO suggest that the motor trade performed strongly in December. The slight increase in Excise Figures confirms this also.

The other taxes, even together, do not amount to very much and are not really worth a comment for a few more months. It will be March before we can see a definite trend, but on these figures, the Government has a chance of reaching its targets.

Oireachtas Committee on European Affairs

The Oireachtas Committee on European Affairs met yesterday to hear briefings on the International Agreement on a Reinforced Economic Union. TASC's Tom McDonnell was one of those invited to address the Committee, along with Dr Alan Ahearne, Professor Karl Whelan and Professor John McHale. Tom's presentation is available here, and there is also a thread on the hearing over on Irish Economy. Comments?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)