The imperative to increase investment as the mechanism for an economic recovey - and to close the public deficit - is begining to gain ground among influential mainstream economists. A recent article in the Financial Times on that theme by its chief economics commentator Martin Wolf was highlighted here.

A follow-up article has elaborated that argument and suggests that incentives to private sector investment are the key to economic revival currently. PE's Michael Burke says that the FT's influential voice on the side of boosting investment is a welcome one, and Burke goes on to argue that hopes of a private sector-led investment recovery seem misplaced, and that arguments to cut the public deficit to achieve that are reckless, and could lead to disaster.

You can read the full post here.

Sunday, 28 February 2010

OECD on Ireland's economic outlook

Paul Sweeney: The OECD is the conservative think tank of the world’s 31 richest states. The latest state to join is Chile, and Ireland has been a member for many years.

This article covers Ireland’s rapid economic success as a poster child held up for developing and Central European countries to emulate. Now, however, we are on our uppers.The article discusses how Ireland declined. It is interesting that it put an big emphasis on the loss of competitiveness (which OECD economists, like their mainstream colleagues here, see largely in terms of short term movements in wages) and much less on the mad tax-cutting policies of Mr McCreevy and Mr Cowan during a raging boom. That view would have nothing to do with their economists’ low tax economic bias? They focus on wages cuts and, disappointingly for a research body, focus on anecdotal rumours of wage falls in the private sector, when the evidence is not there in the CSO data to date.

The article does admit that “there are risks associated with such deflation, particularly as falling incomes will make it harder to ease the burden of outstanding debts.” They are also correct when they conclude that “fostering a new period of strong and sustained growth the coming years will be a challenge.”

This article covers Ireland’s rapid economic success as a poster child held up for developing and Central European countries to emulate. Now, however, we are on our uppers.The article discusses how Ireland declined. It is interesting that it put an big emphasis on the loss of competitiveness (which OECD economists, like their mainstream colleagues here, see largely in terms of short term movements in wages) and much less on the mad tax-cutting policies of Mr McCreevy and Mr Cowan during a raging boom. That view would have nothing to do with their economists’ low tax economic bias? They focus on wages cuts and, disappointingly for a research body, focus on anecdotal rumours of wage falls in the private sector, when the evidence is not there in the CSO data to date.

The article does admit that “there are risks associated with such deflation, particularly as falling incomes will make it harder to ease the burden of outstanding debts.” They are also correct when they conclude that “fostering a new period of strong and sustained growth the coming years will be a challenge.”

Friday, 26 February 2010

Ireland's private debt - is it time to default?

An Saoi: The Central Bank estimates that Irish private debt is €372,000M. The funding of this massive amount is rapidly going to become the key issue in the very near future. Irish resident deposits are just €64,489M from households and €31,024M from Irish business, a total of €95,513M. Even after NAMA, the banks will still be left with loans of more than €300,000M.

Where do they get the money from? Well, I came across the table below on the website of the German magazine Der Spiegel, which explains all. We are drowning in German money.

As can be seen from the graphic, the Germans have lent just over €3,000 per Greek and €2,000 per Italian, compared to about €42,000 for each resident of this State. Now, if I were German I would be dropping one of the “I” in PIIGS, because the Irish position is more akin to that of Iceland than Portugal, Italy Greece or Spain.

Effectively, all future activity in the Irish economy is completely dependent on the view taken by the Treasurers of a handful of German financial institutions. There are huge questions for the Central Bank and their German counterparts as to how these two countries became tied together in this embrace of debt/death.

To put the Irish position into perspective, each Icelander owes approx. €9,000 to the UK arising from the default of their banks, and a further €4,000 to the Netherlands arising out of their State guarantee. The Icelandic people are voting on whether to renege on that deal, and have won the vociferous support of John Kay in his Financial Times column this week to do so. Our debt to the Germans is more than three times greater than that of Iceland to the UK and the Netherlands.

I would suggest that it is time for us to take similar action. Forget about this referendum about children’s rights, we need a referendum to give our children a future. Let us renege on our German debts!

However, this will not happen. The ECB appears to have a friend in the top job in the Central Bank, and the initial investigation into what went wrong will of course be managed by Mr. Regling, who may be predisposed to protect the interests of Germany. You can read his CV here, or you can read a summary in the Oireachtas press release, which states that:

“Mr Regling is a member of the Issing Commission, appointed by Chancellor Merkel in 2008 to advise the German Government on the reform of financial regulation. The Committee completed its work in March 2009.

From 2001 to 2008 he was Director General for Economic and Financial Affairs of the European Commission. Before that, he was a Director General in the German Ministry of Finance where he worked for more than a decade on Economic and Monetary Union in Europe. He also worked in the International Monetary Fund for more than a decade.”

Where do they get the money from? Well, I came across the table below on the website of the German magazine Der Spiegel, which explains all. We are drowning in German money.

As can be seen from the graphic, the Germans have lent just over €3,000 per Greek and €2,000 per Italian, compared to about €42,000 for each resident of this State. Now, if I were German I would be dropping one of the “I” in PIIGS, because the Irish position is more akin to that of Iceland than Portugal, Italy Greece or Spain.

Effectively, all future activity in the Irish economy is completely dependent on the view taken by the Treasurers of a handful of German financial institutions. There are huge questions for the Central Bank and their German counterparts as to how these two countries became tied together in this embrace of debt/death.

To put the Irish position into perspective, each Icelander owes approx. €9,000 to the UK arising from the default of their banks, and a further €4,000 to the Netherlands arising out of their State guarantee. The Icelandic people are voting on whether to renege on that deal, and have won the vociferous support of John Kay in his Financial Times column this week to do so. Our debt to the Germans is more than three times greater than that of Iceland to the UK and the Netherlands.

I would suggest that it is time for us to take similar action. Forget about this referendum about children’s rights, we need a referendum to give our children a future. Let us renege on our German debts!

However, this will not happen. The ECB appears to have a friend in the top job in the Central Bank, and the initial investigation into what went wrong will of course be managed by Mr. Regling, who may be predisposed to protect the interests of Germany. You can read his CV here, or you can read a summary in the Oireachtas press release, which states that:

“Mr Regling is a member of the Issing Commission, appointed by Chancellor Merkel in 2008 to advise the German Government on the reform of financial regulation. The Committee completed its work in March 2009.

From 2001 to 2008 he was Director General for Economic and Financial Affairs of the European Commission. Before that, he was a Director General in the German Ministry of Finance where he worked for more than a decade on Economic and Monetary Union in Europe. He also worked in the International Monetary Fund for more than a decade.”

Thursday, 25 February 2010

Retail workers - near the bottom of the HEAP

Last year, TASC and ICTU published the HEAP Report on income inequality in Ireland. Now, Mandate has published a report - Milking the Recession - showing just how little retail workers earn, and showing how some employers are 'milking the recession' to further depress retail workers' pay and conditions. Click here to read Eoin O'Broin's take on the report.

Wednesday, 24 February 2010

Triple Lock - a lifetime of debt

Slí Eile: Writing in today's Irish Independent, economist David McWilliams in his typically lucid way calls a spade a spade (It's time to shout stop - NAMA is grand larceny). First the bank guarantee, then NAMA and now forced nationalisation (on less favourable terms than if the issue was confronted earlier). He writes:

Karl Whelan wrote early last year:

A crucial feature of the nationalisation approach is that it dramatically reduces the risk involved in having to value the bad loans.

The triple lock would solder the people to the banking system in a suffocating embrace forcing us to borrow from tomorrow to pay for yesterday and, in the process, destroy the opportunities of today.Alone of the parties in the Oireachtas, the Labour Party got it right in September 2008 on the guarantee. Labour got it right on nationalisation in March 2009. And they were right on NAMA.

Karl Whelan wrote early last year:

A crucial feature of the nationalisation approach is that it dramatically reduces the risk involved in having to value the bad loans.

Let us invest in the future

Michael Burke: In today's Financial Times, chief economics commentator Martin Wolf has an interesting piece on how we can get out of the crisis. He argues that conventional wisdom about the prospects for economic recovery, and the policy adjustents that will be necessary, is completely wrong.

"The conventional wisdom is that it will also be possible to manage a smooth exit. Nothing seems less likely."

The reason for his more sober assessment is the trend in private sector financial balances; that is, the growing surpluses of private sector incomes over private sector expenditures. For the OECD as a whole this surplus is projected to reach 7.4% of GDP this year. Six countries, Ireland is one of them, will run surpluses of more than 10% of GDP. In Ireland's case it is projected that the private sector will earn more than it spends to the equivalent of over 15% of GDP, the third highest of OECD economies behind only Spain and Iceland.

This has been dubbed 'the paradox of debt' by Paul Krugman, following the Keynesian notion of the 'paradox of thrift'. The argument is that, while for each highly-indebted company or individual it makes sense to save, or, in the current climate pay down debt, for the economy as a whole it is disastrous. The aggregate saving reduces final demand, both household spending and business investment and thereby deepens the recession. Incomes for individual and companies fall further, so they repsond by cutting expenditures further, and so on.

There are many criticisms of this notion from what has become orthodoxy over the past several years. The only serious one is that, if the private sector saves in this way but continues to consume and invest in the same proportions all that will then happen is that prices will fall, and goods and services will be cheaper at the new, lower level of spending. However, this ignores two trends that occur in crises and are happening currently, most especially in Ireland.

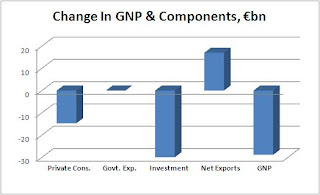

The first is that investment tends to fall much faster than consumption, for obvious reasons. Of a total decline in Ireland's GNP of €28.9bn, personal consumption has fallen by 15.1% (€14.7bn) and investment has fallen by 52.5% (€30bn). In fact, as the data shows, the fall in investment accounts for more than the entire decline in GNP, with the difference mainly accounted by foreign earnings. This pattern, where investment is the main driver of the recession, is replicated across the OECD although in some other countries it is net exports which have also plunged, not private consumption as in Ireland.

The second reason why this orthodox criticism is invalid is the level of debt. As prices fall, as they have in Ireland, the real level of the debt only increases. The many vociferous calls for 'competitive deflation' ignore this fundamental fact. Not only is (un)competitiveness a misdiagnosis of the current situation, but the 'cure', lower prices in Ireland than the rest of the EU would only increase the debt-servicing burden for all who earn their incomes in Ireland, individuals, companies and the government.

To return to the Martin Wolf article, he argues that, while extremely loose monetary policy has been necessary, by itself it stores up two alternative problems, both of which lead ultimately to disaster. One possibility is that cheap money reignites a boom in consumption, which itself just postpones an even bigger future financial crisis. The other possiility is that there is no recovery in consumption and the fiscal poston deteriorates further, to the point of widespread government defaults.

Happily, there is another option. Or actually two, according to Wolf, one of which is a surge in demand in 'emerging' economies. But for highly indebted countries like Ireland the policy option to avert disaster is clear: "a surge in private and public investment in the deficit countries ....[where] .....higher future income would make today’s borrowing sustainable."

He argues that the hope that the world will go back to as it was before the crisis is forlorn one. As we have already seen, it is the huge investment deficit which is driving the recesson, and only an enormous increase in invesment can restore both prior levels of activity and government finances.

"Let us not repeat past errors. Let us not hope that a credit-fuelled consumption binge will save us. Let us invest in the future, instead."

"The conventional wisdom is that it will also be possible to manage a smooth exit. Nothing seems less likely."

The reason for his more sober assessment is the trend in private sector financial balances; that is, the growing surpluses of private sector incomes over private sector expenditures. For the OECD as a whole this surplus is projected to reach 7.4% of GDP this year. Six countries, Ireland is one of them, will run surpluses of more than 10% of GDP. In Ireland's case it is projected that the private sector will earn more than it spends to the equivalent of over 15% of GDP, the third highest of OECD economies behind only Spain and Iceland.

This has been dubbed 'the paradox of debt' by Paul Krugman, following the Keynesian notion of the 'paradox of thrift'. The argument is that, while for each highly-indebted company or individual it makes sense to save, or, in the current climate pay down debt, for the economy as a whole it is disastrous. The aggregate saving reduces final demand, both household spending and business investment and thereby deepens the recession. Incomes for individual and companies fall further, so they repsond by cutting expenditures further, and so on.

There are many criticisms of this notion from what has become orthodoxy over the past several years. The only serious one is that, if the private sector saves in this way but continues to consume and invest in the same proportions all that will then happen is that prices will fall, and goods and services will be cheaper at the new, lower level of spending. However, this ignores two trends that occur in crises and are happening currently, most especially in Ireland.

The first is that investment tends to fall much faster than consumption, for obvious reasons. Of a total decline in Ireland's GNP of €28.9bn, personal consumption has fallen by 15.1% (€14.7bn) and investment has fallen by 52.5% (€30bn). In fact, as the data shows, the fall in investment accounts for more than the entire decline in GNP, with the difference mainly accounted by foreign earnings. This pattern, where investment is the main driver of the recession, is replicated across the OECD although in some other countries it is net exports which have also plunged, not private consumption as in Ireland.

The second reason why this orthodox criticism is invalid is the level of debt. As prices fall, as they have in Ireland, the real level of the debt only increases. The many vociferous calls for 'competitive deflation' ignore this fundamental fact. Not only is (un)competitiveness a misdiagnosis of the current situation, but the 'cure', lower prices in Ireland than the rest of the EU would only increase the debt-servicing burden for all who earn their incomes in Ireland, individuals, companies and the government.

To return to the Martin Wolf article, he argues that, while extremely loose monetary policy has been necessary, by itself it stores up two alternative problems, both of which lead ultimately to disaster. One possibility is that cheap money reignites a boom in consumption, which itself just postpones an even bigger future financial crisis. The other possiility is that there is no recovery in consumption and the fiscal poston deteriorates further, to the point of widespread government defaults.

Happily, there is another option. Or actually two, according to Wolf, one of which is a surge in demand in 'emerging' economies. But for highly indebted countries like Ireland the policy option to avert disaster is clear: "a surge in private and public investment in the deficit countries ....[where] .....higher future income would make today’s borrowing sustainable."

He argues that the hope that the world will go back to as it was before the crisis is forlorn one. As we have already seen, it is the huge investment deficit which is driving the recesson, and only an enormous increase in invesment can restore both prior levels of activity and government finances.

"Let us not repeat past errors. Let us not hope that a credit-fuelled consumption binge will save us. Let us invest in the future, instead."

Monday, 22 February 2010

Deflation, the economy and growth

Michael Taft: Three Sunday articles with some thoughtful comments. First up, the Sunday Tribune and Eamon Quinn’s survey of six economists from across the political spectrum. Though they may differ as to why, none seem to believe the Government will bring the fiscal deficit under control (i.e. Maastricht compliance) by 2014. However, it is Professor Ray Kinsella’s comments that are the most damning:

‘You have to say to yourself, we have had four budgets now and each of those has been deflationary and unemployment will rise to 500,000. We simply can't afford to keep losing that sort of capacity. Firms are failing every day . . Potential is being lost – I can see it in the university students who are leaving the country. I am very clear that continuing the current fiscal policies will destroy the capacity of the Irish economy to recover.’

Second, is Brendan Keenan’s article which argues that leaving the Euro zone to achieve devaluation may not be such an attractive proposition. He concludes:

‘Those countries which think the balance of advantage for them lies with euro membership will have to tailor their policies to achieve growth within the single currency. Ireland has not yet done so. We should worry less about debt and defaults and more about enhancing the economy itself.’

The third observation is by Will Hutton in The Observer who contrasts the 20 economists writing to the Sunday Times, demanding the deficit be cut and be cut now; with the 60 economists writing to the Financial Times who argued for a fiscal policy that promotes growth and recovery. He helpfully links to an IMF paper which studied financial crises in 99 countries. What is the best response for an economy?

‘The best response is increasing capital spending; lift that by 1% of national output and not only are recessions shorter, but there is a permanent boost to economic growth of around a third of 1%.'

So let’s sum up:

• Current polices equals destruction of capacity

• New priority must be about enhancing the economy

• Capital investment has a positive and significant return

It may not be a syllogism in the technical sense. But it is logical.

‘You have to say to yourself, we have had four budgets now and each of those has been deflationary and unemployment will rise to 500,000. We simply can't afford to keep losing that sort of capacity. Firms are failing every day . . Potential is being lost – I can see it in the university students who are leaving the country. I am very clear that continuing the current fiscal policies will destroy the capacity of the Irish economy to recover.’

Second, is Brendan Keenan’s article which argues that leaving the Euro zone to achieve devaluation may not be such an attractive proposition. He concludes:

‘Those countries which think the balance of advantage for them lies with euro membership will have to tailor their policies to achieve growth within the single currency. Ireland has not yet done so. We should worry less about debt and defaults and more about enhancing the economy itself.’

The third observation is by Will Hutton in The Observer who contrasts the 20 economists writing to the Sunday Times, demanding the deficit be cut and be cut now; with the 60 economists writing to the Financial Times who argued for a fiscal policy that promotes growth and recovery. He helpfully links to an IMF paper which studied financial crises in 99 countries. What is the best response for an economy?

‘The best response is increasing capital spending; lift that by 1% of national output and not only are recessions shorter, but there is a permanent boost to economic growth of around a third of 1%.'

So let’s sum up:

• Current polices equals destruction of capacity

• New priority must be about enhancing the economy

• Capital investment has a positive and significant return

It may not be a syllogism in the technical sense. But it is logical.

Sunday, 21 February 2010

No laughing matter

Michael Burke: The British Tory Party have expressed open admiration for the policies pursued in Ireland by the Fianna Fail government. While the entire G20 engaged in fiscal reflation in 2009, only Ireland adopted a contractionary fiscal policy.

Partly as a result, there is a growing interest in Britain in those policies. Meanwhile, letters have been exchanged in the leading newspapers by different groups of economists as to the merits of rapidly adopting contractionary policies which, so far, are unique to Ireland. There is therefore a growing interest in Britain in the nature and impact of recent Irish economic policy. This was the explicit reason for a BBC radio interview with Martin Mansergh which was aired on Sunday morning. The interview is here, almost exactly 15 minutes into the broadcast.

There is perhaps a less-than-commanding grasp of ther government's actual measures, and the degree of levity displayed may disappoint some. But perhaps the most interesting aspect of the interview was the claim that we were fortunate in the timing of the crisis, which gave us until 2012 to face the electorate. Fortune is clearly a relative term.

Partly as a result, there is a growing interest in Britain in those policies. Meanwhile, letters have been exchanged in the leading newspapers by different groups of economists as to the merits of rapidly adopting contractionary policies which, so far, are unique to Ireland. There is therefore a growing interest in Britain in the nature and impact of recent Irish economic policy. This was the explicit reason for a BBC radio interview with Martin Mansergh which was aired on Sunday morning. The interview is here, almost exactly 15 minutes into the broadcast.

There is perhaps a less-than-commanding grasp of ther government's actual measures, and the degree of levity displayed may disappoint some. But perhaps the most interesting aspect of the interview was the claim that we were fortunate in the timing of the crisis, which gave us until 2012 to face the electorate. Fortune is clearly a relative term.

Friday, 19 February 2010

EU calls on Greek population to tighten belts to support wealthy Greek tax dodgers

Michael Burke: Tactical manoeuvring is continuing among European governments to decide exactly how much of the bill will be picked up by who for the financial debacle in Greece. The one thing they all agree is that Greek workers will not be enjoying a bailout of any kind.

Along with the lowest paid and those dependent on public services, Greek workers will bear the brunt of the 'adjustment process', through wage and welfare cuts, pension reductions, an increased retirement age and other austerity measures. The tactical squabbling is that Greece is being pressed by the European Central Bank and leading EU to go even further in the austerity measures it has already announced.At the same time the Greek PASOK government is facing mass demonstrations and strikes, which have encouraged resistance to further austerity measures.

It is noteworthy who will not be targeted. Greece has one of the lowest tax takes in the Euro Area. In the 15 years to 2006, Greek total general government revenues, as a percentage of GDP, were 37.9% compared to an average rate across the Euro Area of 45.3%.[1] This low level of taxation was, in the Greek case, the source of long-standing budget deficits which were hidden from a gullible or complicit EU (or Eurostat) inspectorate over a number of years.

Greek absence of taxation is also a long-standing burden borne by the poor in the country. The Financial Times reports that, according to the official tax returns, there are literally only a handful of Greek citizens who earn more than €1mn per annum registered for tax purposes, and that the Greek shipping magnates and the other rich are registered as 'non-domiciles' in Britain, and consequently pay tax nowhere.

Greece is not in the financial firing line because of a particularly severe recession or an especially blighted banking sector. The latest estimates from Eurostat show that Greece's GDP fell 2% in 2009, but this compares to -4% for the Euro Area and -4.1% for the EU as a whole. This is shown in Figure 1. At the same time, Greece has committed funds to its banking sector equivalent to 11.4% of GDP - far less than the 31.2% EU average (and 232% for Ireland).[2]

Figure 1

The cause of the turmoil in Greece is its high level of government debt, which existed long before the current crisis, combined with a sharply rising budget deficit. Greek government debt as a percentage of GDP has been hovering close to 100% of GDP in all years this century, and is forecast by the EU to rise to 125% of GDP. Greek bond yields were already rising, but were pushed sharply higher by the decision of the European Central Bank, in effect, to remove Greek government bonds from the list of assets it would hold at the end of this year. A reversal of that announcement alone would transform the attitude to Greek government debt, but has not been forthcoming. Likewise, a genuine transformation of the tax system in Greece, as well as rigorous clampdown on tax evasion by the wealthy, would have a dramatic impact on the deficit.

Instead, it seems as the European institutions are trying to get their act together to act as a quasi-IMF, with any support conditional on a deepening of current austerity measures. This is no more likely to be successful in Greece than it has been in Ireland’s case, where deficit projections continue to rise.

As in other countries the rise in the Greek deficit is caused by a slump in taxation receipts, which have fallen by 8.1% in 2009 and which are forecast to fall by over 10% in 2010 [3]. This hole in government finances is itself linked to plummeting levels of investment in the economy. The recession in investment began a year earlier, in 2008, and has already fallen in total by 22.5%, with further falls expected this year [4]. By contrast, the recession-related rise in government spending over the same two years has been just 3.5% [5]. This is shown in the Figure 2 below.

Figure 2

Greece has a narrow tax base, with an unusually wide range of tax-exempt activities. The tax exemptions are revealing as to whose interests are being protected. Among the tax exempt activities:

* Proceeds from the sale of shares that are traded on the Athens Stock Exchange.

* Income from ships and shipping.

* Any dividend received from a Greek company.

* Capital gain from sale of a business between family members.

As a result, any decline in taxable activity leads to a disproportionate decline in tax receipts. This appears to be the case in Greece, where the slump in investment, which is taxable through a variety of levies on goods and services, has led to the decline in aggregate tax receipts and rising public deficits.

Further, the concealment of the actual size of the public deficits appears to have gone unchecked by the EU Commission - as its own 2004 Report into false public accounting in Greece provided no more than a public admonishment, and no programme for change. The new EU investigation however shows that in the years 2000 to 2003, the public deficit was understated by 10.6% of GDP. And, in a tell-tale sign of the unreformed nature of Greek society since the 1970s, more than half of that, 5.5% of GDP, was on military spending.

There is no economic logic behind spending cuts to close the deficit. Higher spending was not the cause of the budget deficit, lower tax receipts are. Worse, since tax evasion is endemic among Greek businesses and the rich, cutting the income of the one section of society that does pay tax, the poor and salaried workers, will reduce taxation revenues further.

The austerity measures now foisted on Greece stand in sharp contrast to the reflationary measures adopted by the major countries across nearly the entire the Euro Area -a policy led by Germany. German has adopted a reflation/stimulus package amounting to 4% of GDP. Germany's measures could have been better targeted. But despite a stagnant 4th quarter of 2009, forecasts for Germany's growth and its deficit are both on an improving trend.

The question is therefore posed, why is a reflationary recipe that clearly works for 'core' Europe deemed unsuitable for Greece? Why can government investment work for Germany, France, Belgium, and so on, but is ruled out in the case of Greece?

The answer may lie elsewhere, in the countries of Eastern Europe. There a number of countries had been hoping to benefit from further EU enlargement, which now seems postponed. Prior to enlargement, the EU demanded continual reform of the Eastern European economies – including further privatisations, liberalisation of the labour markets and a reduction of social spending.

These privatisations facilitated the arrival of Western European and US telecomms, agribusiness and other firms, but above all banks and financial firms. The drive to lower wages and social spending allowed a cheapening of labour, which could be exploited by Western firms, and led to widespread emigration. The removal of local producers in turn expanded the market for Western goods.

This sounds like the package of 'reform measures' to be demanded of Greece in return for any loans. The Greek population is finding that, while all members of the EU are equal, some are more equal than others.

Sources

1.EU Commission, EcoFin, Europea Economic Forecast Autumn 2009, Statistical Annex, Table 36.

2. EU Commission, Euro Area Report, Winter 2009, Table 2.1.

3. Table 36

4. Table 9

5. Table 35

This post has been cross-posted from the Socialist Economic Bulletin.

Along with the lowest paid and those dependent on public services, Greek workers will bear the brunt of the 'adjustment process', through wage and welfare cuts, pension reductions, an increased retirement age and other austerity measures. The tactical squabbling is that Greece is being pressed by the European Central Bank and leading EU to go even further in the austerity measures it has already announced.At the same time the Greek PASOK government is facing mass demonstrations and strikes, which have encouraged resistance to further austerity measures.

It is noteworthy who will not be targeted. Greece has one of the lowest tax takes in the Euro Area. In the 15 years to 2006, Greek total general government revenues, as a percentage of GDP, were 37.9% compared to an average rate across the Euro Area of 45.3%.[1] This low level of taxation was, in the Greek case, the source of long-standing budget deficits which were hidden from a gullible or complicit EU (or Eurostat) inspectorate over a number of years.

Greek absence of taxation is also a long-standing burden borne by the poor in the country. The Financial Times reports that, according to the official tax returns, there are literally only a handful of Greek citizens who earn more than €1mn per annum registered for tax purposes, and that the Greek shipping magnates and the other rich are registered as 'non-domiciles' in Britain, and consequently pay tax nowhere.

Greece is not in the financial firing line because of a particularly severe recession or an especially blighted banking sector. The latest estimates from Eurostat show that Greece's GDP fell 2% in 2009, but this compares to -4% for the Euro Area and -4.1% for the EU as a whole. This is shown in Figure 1. At the same time, Greece has committed funds to its banking sector equivalent to 11.4% of GDP - far less than the 31.2% EU average (and 232% for Ireland).[2]

Figure 1

The cause of the turmoil in Greece is its high level of government debt, which existed long before the current crisis, combined with a sharply rising budget deficit. Greek government debt as a percentage of GDP has been hovering close to 100% of GDP in all years this century, and is forecast by the EU to rise to 125% of GDP. Greek bond yields were already rising, but were pushed sharply higher by the decision of the European Central Bank, in effect, to remove Greek government bonds from the list of assets it would hold at the end of this year. A reversal of that announcement alone would transform the attitude to Greek government debt, but has not been forthcoming. Likewise, a genuine transformation of the tax system in Greece, as well as rigorous clampdown on tax evasion by the wealthy, would have a dramatic impact on the deficit.

Instead, it seems as the European institutions are trying to get their act together to act as a quasi-IMF, with any support conditional on a deepening of current austerity measures. This is no more likely to be successful in Greece than it has been in Ireland’s case, where deficit projections continue to rise.

As in other countries the rise in the Greek deficit is caused by a slump in taxation receipts, which have fallen by 8.1% in 2009 and which are forecast to fall by over 10% in 2010 [3]. This hole in government finances is itself linked to plummeting levels of investment in the economy. The recession in investment began a year earlier, in 2008, and has already fallen in total by 22.5%, with further falls expected this year [4]. By contrast, the recession-related rise in government spending over the same two years has been just 3.5% [5]. This is shown in the Figure 2 below.

Figure 2

Greece has a narrow tax base, with an unusually wide range of tax-exempt activities. The tax exemptions are revealing as to whose interests are being protected. Among the tax exempt activities:

* Proceeds from the sale of shares that are traded on the Athens Stock Exchange.

* Income from ships and shipping.

* Any dividend received from a Greek company.

* Capital gain from sale of a business between family members.

As a result, any decline in taxable activity leads to a disproportionate decline in tax receipts. This appears to be the case in Greece, where the slump in investment, which is taxable through a variety of levies on goods and services, has led to the decline in aggregate tax receipts and rising public deficits.

Further, the concealment of the actual size of the public deficits appears to have gone unchecked by the EU Commission - as its own 2004 Report into false public accounting in Greece provided no more than a public admonishment, and no programme for change. The new EU investigation however shows that in the years 2000 to 2003, the public deficit was understated by 10.6% of GDP. And, in a tell-tale sign of the unreformed nature of Greek society since the 1970s, more than half of that, 5.5% of GDP, was on military spending.

There is no economic logic behind spending cuts to close the deficit. Higher spending was not the cause of the budget deficit, lower tax receipts are. Worse, since tax evasion is endemic among Greek businesses and the rich, cutting the income of the one section of society that does pay tax, the poor and salaried workers, will reduce taxation revenues further.

The austerity measures now foisted on Greece stand in sharp contrast to the reflationary measures adopted by the major countries across nearly the entire the Euro Area -a policy led by Germany. German has adopted a reflation/stimulus package amounting to 4% of GDP. Germany's measures could have been better targeted. But despite a stagnant 4th quarter of 2009, forecasts for Germany's growth and its deficit are both on an improving trend.

The question is therefore posed, why is a reflationary recipe that clearly works for 'core' Europe deemed unsuitable for Greece? Why can government investment work for Germany, France, Belgium, and so on, but is ruled out in the case of Greece?

The answer may lie elsewhere, in the countries of Eastern Europe. There a number of countries had been hoping to benefit from further EU enlargement, which now seems postponed. Prior to enlargement, the EU demanded continual reform of the Eastern European economies – including further privatisations, liberalisation of the labour markets and a reduction of social spending.

These privatisations facilitated the arrival of Western European and US telecomms, agribusiness and other firms, but above all banks and financial firms. The drive to lower wages and social spending allowed a cheapening of labour, which could be exploited by Western firms, and led to widespread emigration. The removal of local producers in turn expanded the market for Western goods.

This sounds like the package of 'reform measures' to be demanded of Greece in return for any loans. The Greek population is finding that, while all members of the EU are equal, some are more equal than others.

Sources

1.EU Commission, EcoFin, Europea Economic Forecast Autumn 2009, Statistical Annex, Table 36.

2. EU Commission, Euro Area Report, Winter 2009, Table 2.1.

3. Table 36

4. Table 9

5. Table 35

This post has been cross-posted from the Socialist Economic Bulletin.

Thursday, 18 February 2010

We need to rethink macroeconomics

Slí Eile: In a paper by staff of the International Monetary Fund (Rethinking Macroeconomic Policy) authors Olivier Blanchard, Giovanni Dell’Ariccia, and Paolo Mauro make the case for smarter macro-economic policy. They openly acknowledge that the economics fraternity had got it wrong on some key issues. They write:

Now that the world economic system came crashing down in a matter of months in 2008 economists in general, and macro-economists in particular, have been in a state of shock. The Great Moderation from the mid-1970s gave way to the Great Recession. A partial counter-cyclical response on the part of some big players including USA, UK and Germany (and aided by the boom in demand in China) prevented the world from slipping into a major crash à la 1929.

Now, there are rumblings of the need to cut off the initial fiscal stimulus and to prioritise fiscal balance especially in those jurisdictions where the public sector debt to GDP ratio has risen sharply (notably the UK and the US). Inspiration has been provided, let it be said, by the ‘brave Irish’ who lead the way in fiscal contraction (not having done a stimulus in the first place). However, as in boom times so also in crisis times we should be wary of the advice coming from macro-economy. Blanchard et al. observe that:

The impact of fiscal contraction since October 2008, in the case of Ireland, opens up an interesting case study. Whatever the future holds, levels of debt – personal, corporate and governmental – will remain very high. It is difficult to see any large reduction in these levels any time soon. The second fact is that unemployment will remain very high and may go higher. Should there be a quick recovery in labour markets (especially in English speaking countries) it is possible that outward migration could assume very large numbers here even as the economy here is technically ‘out of recession’ from later on this year.

The multiplier impacts of fiscal contraction are worrying. All the more worrying is the lack of firm empirical work in this domain beyond what can be gleaned from ESRI working papers (documents emanating from the Department of Finance do not provide the technical detail or modelling to show that the full effect over time of recent spending cuts and tax increases have been taken into account)

Blanchard et al. put in succinctly as follows:

Finally, Blanchard et al write: ‘Identifying the flaws of existing policy is (relatively) easy. Defining a new macroeconomic policy framework is much harder.’ I could not agree more especially in regard to those working in the field of economics and related other disciplines who seek a new baby and not just the old minus the bathwater.

…we thought of monetary policy as having one target, inflation, and one instrument, the policy rate. So long as inflation was stable, the output gap was likely to be small and stable and monetary policy did its job. We thought of fiscal policy as playing a secondary role, with political constraints sharply limiting its de facto usefulness. And we thought of financial regulation as mostly outside the macroeconomic policy framework…The single-minded focus on particular problems sounds very familiar, I think, to an Irish audience. Before the current crisis, the role of the Central Bank and the Financial Regulator was passive, facilitating, and entailed non-directive counselling to banks. The model worked, so it was thought, and any lancing of the property bubble would be by way of a soft landing. Essentially, the failure was to ‘join up the dots’. People saw different parallel realities and imagined that any one or two could go pear shape but not the whole lot at the same time and in a way that showed how interconnected everything was in a way not previously realised. People were still working out of the old textbooks from the 1970s and 1980s. A previous blog has discussed this.

Now that the world economic system came crashing down in a matter of months in 2008 economists in general, and macro-economists in particular, have been in a state of shock. The Great Moderation from the mid-1970s gave way to the Great Recession. A partial counter-cyclical response on the part of some big players including USA, UK and Germany (and aided by the boom in demand in China) prevented the world from slipping into a major crash à la 1929.

Now, there are rumblings of the need to cut off the initial fiscal stimulus and to prioritise fiscal balance especially in those jurisdictions where the public sector debt to GDP ratio has risen sharply (notably the UK and the US). Inspiration has been provided, let it be said, by the ‘brave Irish’ who lead the way in fiscal contraction (not having done a stimulus in the first place). However, as in boom times so also in crisis times we should be wary of the advice coming from macro-economy. Blanchard et al. observe that:

….The rejection of discretionary fiscal policy as a countercyclical tool was particularly strong in academia. In practice, as for monetary policy, the rhetoric was stronger than the reality. Discretionary fiscal stimulus measures were generally accepted in the face of severe shocks (such as, for example, during the Japanese crisis of the early 1990s)….They go on to say that:

…As a result, the focus was primarily on debt sustainability and on fiscal rules designed to achieve such sustainability. To the extent that policymakers took a long-term view, the focus in advanced economies was on prepositioning the fiscal accounts for the looming consequences of aging…In summary, many economists and some policy-makers forgot about discretionary fiscal policy instruments along with all the other tools available (exchange rate, interest rates, regulation etc). The point is all the more relevant in a small open economy within the European Monetary Union such as Ireland.

The impact of fiscal contraction since October 2008, in the case of Ireland, opens up an interesting case study. Whatever the future holds, levels of debt – personal, corporate and governmental – will remain very high. It is difficult to see any large reduction in these levels any time soon. The second fact is that unemployment will remain very high and may go higher. Should there be a quick recovery in labour markets (especially in English speaking countries) it is possible that outward migration could assume very large numbers here even as the economy here is technically ‘out of recession’ from later on this year.

The multiplier impacts of fiscal contraction are worrying. All the more worrying is the lack of firm empirical work in this domain beyond what can be gleaned from ESRI working papers (documents emanating from the Department of Finance do not provide the technical detail or modelling to show that the full effect over time of recent spending cuts and tax increases have been taken into account)

Blanchard et al. put in succinctly as follows:

Furthermore, the wide variety of approaches in terms of the measures undertaken has made it clear that there is a lot we do not know about the effects of fiscal policy, about the optimal composition of fiscal packages, about the use of spending increases versus tax decreases, and the factors that underlie the sustainability of public debts, topics that had been less active areas of research before the crisis.However, for the sake of balance it should be pointed out that Blanchard et al. are not calling for the baby to be thrown out with the bathwater (to use their words).

..It is important to start by stating the obvious, namely, that the baby should not be thrown out with the bathwater. Most of the elements of the precrisis consensus, including the major conclusions from macroeconomic theory, still hold...Fiscal sustainability is of the essence, not only for the long term, but also in affecting expectations in the short term’ (P10).Their paper is highly nuanced and should not be cited as fundamentally at odds with orthodoxy. There is nothing in their line of argument to suggest that the Irish Government is being anything but ‘fiscally responsible’. The details of how they are going about it may be questioned from within and outside the country. But, as Enda Kenny recently said ‘we have no problems with an adjustment of €4bn.

Finally, Blanchard et al write: ‘Identifying the flaws of existing policy is (relatively) easy. Defining a new macroeconomic policy framework is much harder.’ I could not agree more especially in regard to those working in the field of economics and related other disciplines who seek a new baby and not just the old minus the bathwater.

The inequality cascade

Over on Irish Economy, Philip Lane links to this graph from the Economist website, showing the likelihood of a son with a university-educated father going on to get a degree; the graph also correlates earnings with paternal education. Click here to see how Ireland shapes up.

Your Country Your Call

Nat O'Connor: In the spirit of Kennedy, asking us to think of what we can do for our country, President McAleese has launched a national competition: Your Country Your Call.

"Your Country, Your Call gives you the chance to share your creativity to give life to new industry, revitalise or revolutionise an existing market, or even change the way we do business entirely. It's not about creating new products. It's about creating something that will make a long term positive impact on the future of Ireland, its people, and its economy"

Rather aptly, the competition website has a 'ticking clock' with 72 days allowed for entries. The top 20 ideas will be listed and two final winners will receive €500,000 and other support to implement their ideas.

You can read more about it in the Examiner or Irish Times (which also summarised the competition rules).

This competition is an open door to give some progressive ideas a wider hearing...

"Your Country, Your Call gives you the chance to share your creativity to give life to new industry, revitalise or revolutionise an existing market, or even change the way we do business entirely. It's not about creating new products. It's about creating something that will make a long term positive impact on the future of Ireland, its people, and its economy"

Rather aptly, the competition website has a 'ticking clock' with 72 days allowed for entries. The top 20 ideas will be listed and two final winners will receive €500,000 and other support to implement their ideas.

You can read more about it in the Examiner or Irish Times (which also summarised the competition rules).

This competition is an open door to give some progressive ideas a wider hearing...

Tuesday, 16 February 2010

Latest rental figures

The latest DAFT report is out covering rents, and PE's Michael Taft has written the quarterly commentary. The headline news is that rents have 'stabilised' and have started to rise - though whether this presages a long-term upward trend remains to be seen. However, the commentary goes behind the numbers to examine a

' . . . fragmented, under-capitalised 'cottage' industry lacking the professionalism and modern synergy with a strong regulatory culture that prevails in other EU countries.'

The full report and commentary can be downloaded here.

' . . . fragmented, under-capitalised 'cottage' industry lacking the professionalism and modern synergy with a strong regulatory culture that prevails in other EU countries.'

The full report and commentary can be downloaded here.

Monday, 15 February 2010

“…all of the adjustments are being done to impress the rating agencies and international capital markets….”

Slí Eile: So writes Michael Casey, former chief economist with the Central Bank and currently board member of the International Monetary Fund. He then makes the extraordinary claim that (‘The reputations sent up in smoke’)

Take these statements in conjunction with what another economist, Pat McArdle, wrote recently Irish Times (‘Effective measures are needed to stop the rot from spreading’)

The single-minded focus on correcting Ireland’s fiscal stance, reducing the public sector deficit and competitive devaluation (i.e. cutting wages) is now the only moral narrative in town. Jobs, migration, living standards of the poor – are secondary to the One Policy Target = reduce the fiscal deficit to a much lower level. But, how much lower? At least two interesting facts seem to be emerging in the current debate and debacle over Greece and associated ‘high debt’ countries:

But, suddenly, the spin is turning to the following type of meta-narrative:

What can be learned from the fiscal debacle of the noughties?

In a paper presented by Philip Lane at the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland, recently (A New Fiscal Framework for Ireland) a case is made for

Would such a mechanism assess the wider social and economic benefits and costs of spending and taxes as a necessary corollary to judging the appropriate level of borrowing, spending and taxes taking into account, in so far as data permit, the likely monetary and non-monetary value of adjustments to societal assets and liabilities. Reducing current state liabilities through public sector downsizing as advocated by most mainstream economists may very well corrode valuable public assets not to mention social solidarity and cooperation – which are assets in themselves.

“..Our Government and the EU Commission have sold out to the rating agencies, none of whom cares about unemployment or emigration.”Whatever one may think of our Government or parts of the current EU Commission it has to be pointed out that we owe much to the European Union not least because of the excesses and poverty of ambition of our native gombeen classes. (Where would gender equality be, today, were it not for the EU)

Take these statements in conjunction with what another economist, Pat McArdle, wrote recently Irish Times (‘Effective measures are needed to stop the rot from spreading’)

‘With hindsight, we were fortunate to have gone down the road we did. The alternative of job creation schemes or expansionary measures would have been disastrous.’‘Job creation schemes’ and ‘expansionary measures’. What a terrible vista.

The single-minded focus on correcting Ireland’s fiscal stance, reducing the public sector deficit and competitive devaluation (i.e. cutting wages) is now the only moral narrative in town. Jobs, migration, living standards of the poor – are secondary to the One Policy Target = reduce the fiscal deficit to a much lower level. But, how much lower? At least two interesting facts seem to be emerging in the current debate and debacle over Greece and associated ‘high debt’ countries:

- The Stability and Growth Pact targets are dead, long live the SGP

- There is a very widely shared consensus that all roads must lead to fiscal rectitude and all roads to poverty reduction, sustainable growth and full employment (if people care about these things) lead from a balanced or near balanced budget – in the long-run.

- The degree of unemployment and wage reductions needed to ‘clear markets’ and balance the public sector books may be too much for people to take. We still live in a democracy.

- The world recovery may be a lot slower and lot more jobless in a way that offer little solace to a small open economy stuck with a dysfunctional banking system and a low-tax regime.

But, suddenly, the spin is turning to the following type of meta-narrative:

“…in the year of 2008 the world economy collapsed and plucky Ireland went down fast as output and tax receipts went into free fall…but while other countries in a similar situation dithered the brace Irish and their unpopular Government took brave (and painful – everything must be painful) decisions ….and hey presto from 2011 onwards Ireland was rewarded with a reducing deficit, increased exports and stabilisation in unemployment…too bad many had to emigrate and other indices of social strife, poverty and ill-health went up for a while…that’s life”Time will tell. However, missing from the debate up to now:

- A comprehensive, progressive, convincing, numbers-backed Alternative Economic Strategy

- A political movement with the backing of more than 40% of the population and with enough electoral backing positioned to implement such a Strategy not in some distant future election but at the next one which has to be within the next 27 months.

What can be learned from the fiscal debacle of the noughties?

In a paper presented by Philip Lane at the Statistical and Social Inquiry Society of Ireland, recently (A New Fiscal Framework for Ireland) a case is made for

- New Fiscal rules

- A Fiscal Policy Council to monitor and manage fiscal adjustments (the never-again agenda)

Would such a mechanism assess the wider social and economic benefits and costs of spending and taxes as a necessary corollary to judging the appropriate level of borrowing, spending and taxes taking into account, in so far as data permit, the likely monetary and non-monetary value of adjustments to societal assets and liabilities. Reducing current state liabilities through public sector downsizing as advocated by most mainstream economists may very well corrode valuable public assets not to mention social solidarity and cooperation – which are assets in themselves.

Competitiveness myths ...

"There is a real danger that, encouraged by the economists’ chorus on the need to cut costs as the way to get us out of our current economic troubles, the government will actually undermine Ireland’s long-term competitive position through cutbacks in research and education (in fact, such cutbacks are already being imposed). We desperately need to substitute serious evidence-based analysis for the rote incantation of inherited mantras which currently passes for expert economic advice in the realm of competitiveness policy in this country".

That is the conclusion reached by Proinnsias Breathnach; you can read his full post on Ireland after NAMA here.

That is the conclusion reached by Proinnsias Breathnach; you can read his full post on Ireland after NAMA here.

Sunday, 14 February 2010

George Lee

Slí Eile: In the spirit of playing the ball and not the man...there may be more to George Lee than George Lee. Recent media reports suggest...well...a possibly different approach or emphasis on economic policy and that may explain in part his sudden departure from Fine Gael and political life. If we are to believe the newspapers George was, compared to FG colleagues, less enthusiastic about deflation and more supportive of fiscal stimulus as well as measures to protect the unemployed as well as conserve universal child benefit (a forensic search on the Oireachtas website might be instructive in this regard). Or shall we say deflation with a human face. I wonder if George would have been more at home in mainstream European social democracy? Certainly not in mainstream current-day Irish political economy. I specifically recall him worrying about the scale of deflationary impact in last year's April budget (when he was still a journalist)

Saturday, 13 February 2010

With friends like these (once more on Greece)

Michael Burke: There are widespread reports including here, that the meeting of European Finance Ministers will agree to a series of measures aimed at preventing a deepening of the financial crisis as it affects Greece, and threatens to engulf a number of EU countries.

The terms of the bailout and its extent are unclear. But what is clear is that Greek workers will not be enjoying a bailout of any kind. Along with the lowest paid and those dependent on public services, Greek workers will bear the brunt of the 'adjustment process', through wage and welfare cuts, pension reductions, an increased retirement age and other austerity measures.

It is noteworthy who will not be targeted. Greece has one of the lowest tax takes in the Euro Area. In the 15 years to 2006, Greek total general government revenues as a percentage of GDP were 37.9% compared to an average rate across the Euro Area of 45.3% (and 36.3% for Ireland)*. This low level of taxation was, in the Greek case, the source of long-standing deficits which were hidden from a gullible EU (or Eurostat) inspectorate over a number of years. Greece taxation is also a long-standing burden borne by the poor. The FT reports that, according to tax returns, there are only literally a handful of Greek citizens who earn more than €1mn per annum, and that the Greek shipping magnates and others are registered as 'non-domiciles' in Britain, and consequently pay tax nowhere.

Greece has been in the firing line because of its high level of government debt, which existed long before the current crisis. Greek government debt as a percentage of GDP has been hovering close to 100% of GDP in all the years of this century, and is forecast by the EU to rise to 125% of GDP. The bond market fear which has pushed Greek yields higher was exacerbated by the decision of the European Central Bank in effect to remove Greek government bonds from the list of assets it would hold at the end of this year. A reversal of that announcement alone would transform the attitude to Greek government debt, but has not been forthcoming. Likewise, a genuine transformation of the tax system in Greece, as well as rigorous clampdown on tax evasion by the wealthy, would have a dramatic impact on the deficit.

Instead, it seems as if the European institutions are intent on acting as a quasi-IMF, with any support conditional on a deepening of current austerity measures. This is no more likely to be successful in Greece than it has been in Ireland. Greece is actually experiencing a mild recession compared to most industrialised countries. GDP is expected to fall by just 1.4% over 2009/2010. Yet investment is expected to decline by 25.5%, having started to fall a year earlier. It is this investment slump which has caused tax revenue to decline by 8.8%, which in turn is the source of the rise in the deficit. By contrast, the recession-related rise in government spending over the same two years has been just 3.5%.

The austerity measures foisted on Greece stand in sharp contrast to the reflationary measures adopted all across the Euro Area, and led by Germany (with the stark exception of Ireland). German reflation has amounted to 4% of GDP. The measures could have been better-targeted. But despite a stagnant Q4, forecasts for Germany's growth and its deficit are both on an improving trend. The question is therefore posed, why is a reflationary recipe that clearly works for 'core' Europe deemed unsuitable for Greece? Why can government investment work for Germany, France, Belgium, and so on, but is ruled out in the case of Greece?

The answer may lie elsewhere, in the countries of Eastern Europe. There, a number of countries had been hoping to benefit from further EU enlargement, which now seems postponed. Prior to enlargement, the EU demanded continual reform of the Eastern European economies – including further privatisations, liberalisation of the labour markets and a reduction of social spending.

The privatisations facilitated the arrival of Western European and US telecoms, agribusiness and other firms, but above all banks and financial firms. The drive to lower wages and social spending allowed a cheapening of labour, to be exploited by Western firms, and led to widepsread emigration. The removal of local producers expanded the market for Western goods.

This sounds like the package of 'reform measures' to be demanded of Greece in return for any loans. Greece may soon find that, while all members of the EU are equal, some are more equal than others.

* All data from the EU Commission Area Report, Winter 2009, Statistical Anne, unless otherwise stated.

The terms of the bailout and its extent are unclear. But what is clear is that Greek workers will not be enjoying a bailout of any kind. Along with the lowest paid and those dependent on public services, Greek workers will bear the brunt of the 'adjustment process', through wage and welfare cuts, pension reductions, an increased retirement age and other austerity measures.

It is noteworthy who will not be targeted. Greece has one of the lowest tax takes in the Euro Area. In the 15 years to 2006, Greek total general government revenues as a percentage of GDP were 37.9% compared to an average rate across the Euro Area of 45.3% (and 36.3% for Ireland)*. This low level of taxation was, in the Greek case, the source of long-standing deficits which were hidden from a gullible EU (or Eurostat) inspectorate over a number of years. Greece taxation is also a long-standing burden borne by the poor. The FT reports that, according to tax returns, there are only literally a handful of Greek citizens who earn more than €1mn per annum, and that the Greek shipping magnates and others are registered as 'non-domiciles' in Britain, and consequently pay tax nowhere.

Greece has been in the firing line because of its high level of government debt, which existed long before the current crisis. Greek government debt as a percentage of GDP has been hovering close to 100% of GDP in all the years of this century, and is forecast by the EU to rise to 125% of GDP. The bond market fear which has pushed Greek yields higher was exacerbated by the decision of the European Central Bank in effect to remove Greek government bonds from the list of assets it would hold at the end of this year. A reversal of that announcement alone would transform the attitude to Greek government debt, but has not been forthcoming. Likewise, a genuine transformation of the tax system in Greece, as well as rigorous clampdown on tax evasion by the wealthy, would have a dramatic impact on the deficit.

Instead, it seems as if the European institutions are intent on acting as a quasi-IMF, with any support conditional on a deepening of current austerity measures. This is no more likely to be successful in Greece than it has been in Ireland. Greece is actually experiencing a mild recession compared to most industrialised countries. GDP is expected to fall by just 1.4% over 2009/2010. Yet investment is expected to decline by 25.5%, having started to fall a year earlier. It is this investment slump which has caused tax revenue to decline by 8.8%, which in turn is the source of the rise in the deficit. By contrast, the recession-related rise in government spending over the same two years has been just 3.5%.

The austerity measures foisted on Greece stand in sharp contrast to the reflationary measures adopted all across the Euro Area, and led by Germany (with the stark exception of Ireland). German reflation has amounted to 4% of GDP. The measures could have been better-targeted. But despite a stagnant Q4, forecasts for Germany's growth and its deficit are both on an improving trend. The question is therefore posed, why is a reflationary recipe that clearly works for 'core' Europe deemed unsuitable for Greece? Why can government investment work for Germany, France, Belgium, and so on, but is ruled out in the case of Greece?

The answer may lie elsewhere, in the countries of Eastern Europe. There, a number of countries had been hoping to benefit from further EU enlargement, which now seems postponed. Prior to enlargement, the EU demanded continual reform of the Eastern European economies – including further privatisations, liberalisation of the labour markets and a reduction of social spending.

The privatisations facilitated the arrival of Western European and US telecoms, agribusiness and other firms, but above all banks and financial firms. The drive to lower wages and social spending allowed a cheapening of labour, to be exploited by Western firms, and led to widepsread emigration. The removal of local producers expanded the market for Western goods.

This sounds like the package of 'reform measures' to be demanded of Greece in return for any loans. Greece may soon find that, while all members of the EU are equal, some are more equal than others.

* All data from the EU Commission Area Report, Winter 2009, Statistical Anne, unless otherwise stated.

Greek strikes and protests

Michael Burke: The scale of the action by Greek unions is evident even from this short clip. ADEDY is the main public sector trade union which organised the strike. Its General Secrtary has announced that his organisation had decided to support the call of General Confederation of Labour GSEE’s (which operates in the private sector) for a second General Strike on February 24th.

Friday, 12 February 2010

How fortunate to have avoided such disaster

Michael Taft: Pat McArdle celebrates the fact that the Fianna Fail government has taken up the austerity cudgels:

‘With hindsight, we were fortunate to have gone down the road we did. The alternative of job creation schemes or expansionary measures would have been disastrous.’

Let’s run through some comparative data to see just how ‘fortunate’ we have been and how we avoided ‘disaster’. These cover the years 2007-2010 – three years of recession (for Ireland, anyway). The Euro zone data and estimates come from the EU Statistical Annex. Irish data and estimates come from the recent ESRI Quarterly Report (except for Irish domestic demand which comes from the EU estimates).

• Euro zone GDP is estimated to fall by -2.7 percent. Irish GNP is estimated to contract by -13.3 percent.

• Euro zone GDP per capita is estimated to fall by -4 percent. Irish GNP (for the domestic economy) per capita is estimated to fall by -16.1 percent.

• Euro zone domestic demand is expected to fall by -2.3 percent. In Ireland it is expected to fall by -19.3 percent

• Euro zone consumer spending will hardly fall at all: -0.4. In Ireland, consumer spending will fall by -8.8 percent.

• Total investment in the Euro zone is projected to fall by -12.8 percent. In Ireland, the fall is projected to by -51.7 percent.

• Non-property investment is estimated to all by -17.7 percent in the Euro zone. It is estimated to fall by -38.9 percent.

• In the Euro zone, employment is projected to fall by -3 percent. In Ireland it is projected to fall by -12.7 percent.

Pity those other Euro zone countries with their ‘job creation schemes and expansionary measures’. We’re just ‘fortunate’ that Fianna Fail is in power.

‘With hindsight, we were fortunate to have gone down the road we did. The alternative of job creation schemes or expansionary measures would have been disastrous.’

Let’s run through some comparative data to see just how ‘fortunate’ we have been and how we avoided ‘disaster’. These cover the years 2007-2010 – three years of recession (for Ireland, anyway). The Euro zone data and estimates come from the EU Statistical Annex. Irish data and estimates come from the recent ESRI Quarterly Report (except for Irish domestic demand which comes from the EU estimates).

• Euro zone GDP is estimated to fall by -2.7 percent. Irish GNP is estimated to contract by -13.3 percent.

• Euro zone GDP per capita is estimated to fall by -4 percent. Irish GNP (for the domestic economy) per capita is estimated to fall by -16.1 percent.

• Euro zone domestic demand is expected to fall by -2.3 percent. In Ireland it is expected to fall by -19.3 percent

• Euro zone consumer spending will hardly fall at all: -0.4. In Ireland, consumer spending will fall by -8.8 percent.

• Total investment in the Euro zone is projected to fall by -12.8 percent. In Ireland, the fall is projected to by -51.7 percent.

• Non-property investment is estimated to all by -17.7 percent in the Euro zone. It is estimated to fall by -38.9 percent.

• In the Euro zone, employment is projected to fall by -3 percent. In Ireland it is projected to fall by -12.7 percent.

Pity those other Euro zone countries with their ‘job creation schemes and expansionary measures’. We’re just ‘fortunate’ that Fianna Fail is in power.

A pessimistic Stiglitz

Today's Guardian carries a deeply pessimistic interview with Joseph Stiglitz, who notes that "Plans to re-regulate the financial markets have run into a political quagmire and there has been a resurgence of deficit fetishism", and goes on to express surprise at at how fast the forces in favour of the pre-2007 status quo have re-grouped. "The optimist in me is hopeful we won't need another crisis to finally motivate the political process," he said. "The pessimist in me says it may need to happen."

You can read the full interview here.

You can read the full interview here.

Falling prices and low-income households

"Price deflation for low income families will be experienced at the lower rate of 2.2% and will do little to compensate for the real drop in incomes produced by Budget 2010. Indeed for many families household income will reduce further as a consequence of the increased costs of education, energy, health and transport.

In this context any change to either the Minimum Wage or pay rates agreed through Registered Employment Agreements will have the effect increasing hardship for those individuals and families currently living on or below the Governments income poverty line"

You can read the rest of Eoin O'Broin's post on Politico here.

In this context any change to either the Minimum Wage or pay rates agreed through Registered Employment Agreements will have the effect increasing hardship for those individuals and families currently living on or below the Governments income poverty line"

You can read the rest of Eoin O'Broin's post on Politico here.

Thursday, 11 February 2010

Basel III, pensions and the recapitalisation of Irish banks

An Saoi: Wednesday’s Financial Times had a very interesting article on proposed changes in banking rules under Basel III. Sensibly, the Bank of International Settlements is proposing that pension deficits should be deducted when calculating net Tier One capital. The pension obligations are long-term liabilities and should of course be deducted from core assets, as they are a core liability.

British Banks are up in arms over the proposal as many have huge deficits. What is the position of the Irish banks?

Bank of Ireland had a deficit of €1,478M at 31st March 2009 and Allied Irish Banks admitted to a deficit €1,263M at 30th June 2009. It appears that these two banks will require perhaps a further €3,000M, on top of current estimates, which the Government and the Governor of the Central Bank has glossed over to date. Certainly the failure of Dr. Honohan to bring the BIS’s proposal to the attention of the Irish public in his utterances about recapitalisation raises many questions in relation to his impartiality.

This additional cost to ensure that the pensions of the fat cats who got us into this trouble are secured is surely one step too far?

British Banks are up in arms over the proposal as many have huge deficits. What is the position of the Irish banks?

Bank of Ireland had a deficit of €1,478M at 31st March 2009 and Allied Irish Banks admitted to a deficit €1,263M at 30th June 2009. It appears that these two banks will require perhaps a further €3,000M, on top of current estimates, which the Government and the Governor of the Central Bank has glossed over to date. Certainly the failure of Dr. Honohan to bring the BIS’s proposal to the attention of the Irish public in his utterances about recapitalisation raises many questions in relation to his impartiality.

This additional cost to ensure that the pensions of the fat cats who got us into this trouble are secured is surely one step too far?

Wednesday, 10 February 2010

Spring Alliance ...

Paul Sweeney: In 2009, the Spring Alliance was established with the four key civil society groups within the European Union: the European Environmental Bureau, the European Trade Union Confederation, the Social Platform and CONCORD, the body representing NGOs in Europe.

Spring Alliance has set out an agenda for the next decade, laid down in their Spring Alliance Manifesto. It has already had two debates with President Barroso on the results, and this manifesto formed the background for many contributions to the consultation on the EU-2020 Strategy being debated by the Commission.

The see five major challenges facing Europe:

The first challenge: climate change and loss of biodiversity and natural resources.

The second challenge: global inequalities between North and South are growing, and fundamental rights violations remain widespread.

The third challenge: the EU’s focus on competitiveness and deregulation has failed to serve the public good.

They argue that, since 2005, the EU has made a push to increase the deregulation of its markets, including its labour market, in accordance with its “Lisbon” growth and jobs strategy. This has had a detrimental effect on European society, causing a rise in low-quality work and failing to reduce poverty. The Lisbon strategy, with its strong emphasis on competitiveness, also had an adverse effect in the environmental domain, by halting or slowing down the adoption of legislation, including in the area of climate change.

In addition to these trends, today we’re facing a global economic crisis that has been triggered by the same philosophy of deregulation, which gave rise to irresponsible lending and negligence on the part of weak regulatory bodies. As a consequence, unemployment is now rising, and public debt is increasing.

The fourth challenge: inequalities in wealth distribution are increasing, putting the cohesion of our societies at risk.

The Spring Alliance notes that “79 million people in the EU are living in poverty, affecting one child out of five. Although many of these people have full-time jobs or receive pensions or benefits, their income is still too low to stop them from falling into poverty.”

Finally: the gap is widening between the EU and its citizens

It is stated by Spring Alliance that “The majority of the EU population feels disconnected from EU decision-making processes. National politicians often consider “Brussels” as an external power, and sometimes use it as scapegoat for unpopular decisions. This further undermines the EU’s credibility and its capacity to lead its citizens through difficult times.”

The Spring Alliance suggests ways in which these challenges can be addressed with the EU taking a lead. Further information is available on their website.

Spring Alliance has set out an agenda for the next decade, laid down in their Spring Alliance Manifesto. It has already had two debates with President Barroso on the results, and this manifesto formed the background for many contributions to the consultation on the EU-2020 Strategy being debated by the Commission.

The see five major challenges facing Europe:

The first challenge: climate change and loss of biodiversity and natural resources.